“There already are enough useful objects designed to perfectly fulfil their function, what I am looking for is to communicate and interact with the object.”

- Cinzia Rugger

Lobster Telephones That Ring

“Although Surrealism is often seen as escapist”, this show points out, “its founders were more interested in changing perceptions of reality.” Well of course! It’s a shame it still needs to be said, but as it does it’s better to say it. And there seems little doubt that the movement’s popular association with painting and drawing is because they’re associated with escaping into another world.

Design, though? It also says “Surrealism liberates design from the rational and utilitarian.” I hate to be a killjoy. But don’t we want design to be a bit utilitarian, or at least useable?

Dali’s famous Lobster Telephone isn’t just here but adorning the poster. We’re told that Edward James commissioned eleven of them for his various residences, which do seem to have been working models. But even if we still had cradle phones, let’s face it you wouldn’t want one of the cumbersome things yourself, wrapping it round your head only to hear from some dodgy call centre calling themselves “your bank”.

The show quotes Isamu Noguchi, “everything is sculpture”. Which sounds more a Bauhaus statement than Surrealist. The Bauhaus credo was of course ‘form follows function’, which the show counters with ‘form follows fantasy’. But this ignores the degree to which Surrealism was intended as sabotage.

Take Many Ray’s famous ’Gift’ (1921, above). It clearly wasn’t designed to ever be used as an iron, but to be disruptive. Just like an actual iron like that would tear through shirts, Surrealism intends to tear through art and society. Strictly its Dada rather than Surreal, but the slippage between one and the other is considerable. And as Dada was anti-art, wouldn’t Surrealist design need to be anti-design?

Similarly, some of Duchamp’s readymades show up. But the whole point was to tear them from their function, sometimes quite literally, and put them somewhere where they didn’t fit. People have used his urinal for its original purpose, but only as a prank. It’s similar to the way that words, when taken in isolation, seem to descend into prattle. Duchamp wasn’t interested in them as works of design, nor of designing with them.

Furthermore, we use design as a synonym for plan, in phrases such as “by design”. Whereas Surrealist artists frequently worked by automatist (chance and/or unconscious) processes. You could claim that to come from the authentic Surreal region of art it needs to involve, as said of the recent ‘British Surrealism’ show, “artists surprised by what springs from their own hands.”

And further furthermore, early on the show gives us Dali’s ’Metamorphosis of Narcissus’ (1937, above). Even if we were to somehow miss it in the work, the focus on transformation’s there in the title. Things are not still or separate, but ever-changing, to the point where things aren’t really even things any more. The show refers to these as “ungoverned shapes”. How can you convey this with real world objects?

As it turns out, you can. Dali’s ’Cats Cradle Hands’ chair (c. 1936) transforms its back into arms and hands. Or Meret Oppenheim’s ’Traccia’ (1939, both above) gives a table bird’s feet.

Ray and Charles Eames’ ’Moulded Plywood Sculpture’ (1943) has the sinuous curves often found in Surrealism, but almost works better for being ‘real’. They seem to flow so, the eye can’t really get a purchase on them and hopeless follows them round and round. It’s not a ceaseless Moebius strip, ever-twisty and ever-turny, but it still looks like one. Sculpture is surely, by definition, about solid and fixed objects. Well, not here.

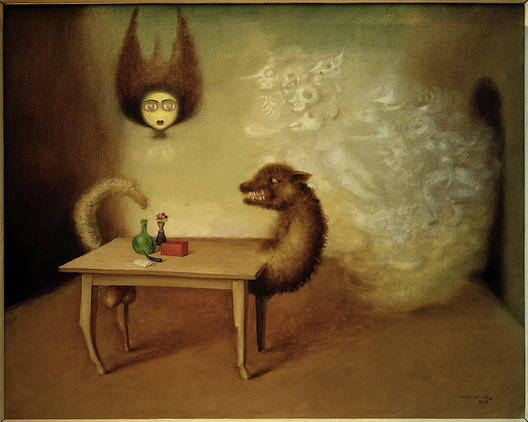

In fact Surrealist artists had pretty much a penchant for realising in real life things they’d originally painted. Dali’s sofa of Mae West’s lips is on show here, but us Brighton folk are familiar with another version in our local Museum. So more interesting to me was Victor Brauner’s ’Psychological Space’ (1939, above). The show displays the original painting, from which he made that wolf table for a 1947 exhibition. Why do such a thing? A quote from Shiro Kuramata might come closer: “Enchantment should also be considered a function.”

As seen before, over the Tate’s recent ‘Surrealism Beyond Borders’ show, a large part of Surrealism was about having an almost animist relationship with charged objects. “Its perspective comes from recognising objects as entities; to be recognised, to enter into accordances with, the most humble modern objects seen as possessing spirits.”

It’s true that, to intensify this feeling, they tended to prefer objects whose origin was somehow mysterious, stumbled upon in flea markets and the like. But there’s nothing essential about this. It’s similar to the way couples can relish the tale of the unusual way they met, but that’s not essential to being in a couple.

However, you don’t have to think about this for very long before you realise you’re being asked to treat functional things as though they were some combination of art object and magical force. The problem then becomes that the designer can’t pre-determine this relationship, which is all between the object and the user.

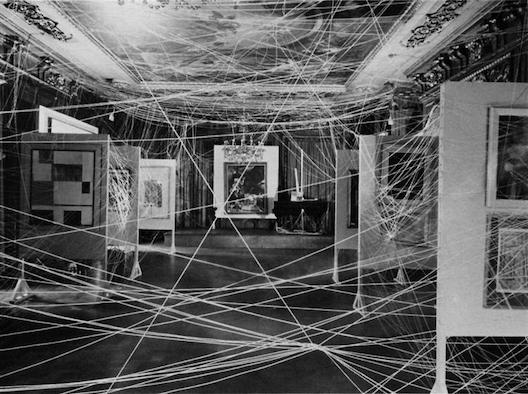

And speaking of exhibitions, they seem important here in themselves. Or at least the ones the movement itself staged. As the show points out “Surrealists approached [them] as collective artworks”. Just as with Dada, they were part of Surrealist practice, not just a means by which to display already finished works. In fact the works just became materials for the overall show, with obligations such as displaying them clearly being discarded. There’s photos of various exhibitions here which are effectively installations, the opposite of neatly ordered and carefully labelled rooms like the one we’re in. A particular favourite of mine is is Duchamp’s ’Sixteen Miles Of String’ for a New York show in 1942. (Photo below by John D Schiff.)

And there seems a similarity with Dali’s home designs for Edward James’ Monkton House, where everything seems incorporated, integral to the Surrealist concept, nothing left to be ‘normal’. Or his film or theatre sets, or window displays for Bonwitt Teller, (1939, above). And these do look different, and more effective, than when individual elements are ripped from the room and shown as isolated artworks. It’s a kind of fishbowl design, where part of the point is we know we’re looking at real objects. But they’re there for us to look at rather than engage with. As much as it is design its design as display, not use.

Design Into Dollars?

The skeptical reader may note how much Dali has dominated things so far. And its unsurprising that the man soon anigrammatically nicknamed Avida Dollars led the way in this direction. (It’s a bit of a tangent but the show includes 'Destino’, the animation he made for Disney. In 1945/6, but not realised until 2003. And it’s notable how easily his slick later style blends with the smooth Disney look.)

After all… shop windows, objects made to be talking pieces for toffs, don’t these consumer items seem a world away from an art movement that declared itself revolutionary? How does this fit with the Tate show which largely focused on colonial subjects? And couldn’t that be said to be inherent in this direction? Enchantment, like most desirable things, turns out to be a luxury product. The rich, after all, live their lives on show, consume conspicuously, while the rest of us make do with frill-less functionality.

Or take ’Horse Lamp’ by Front Design (2006, above). It looks a surreal triumph, a full-size model of a horse made to do no more than hold up a lamp. Most of us would literally not have room for such a thing. Except you can buy it, given the will and a spare five grand. Which kind of transforms it from absurd object to click and collect. (Well, okay, you’d probably ask for it to be delivered.)

Or, perhaps more strongly still, Carlo Mollino’s 1938 designs for Casa Miller, which included a torso-shaped hole in a wall. Is there a left-field charm to this? Yes. But that charm all belongs to Magritte, a Surrealist artist I’m not even especially keen on. In such moments it’s hard not to think of those who crowbar Banksys off public walls for private clients. One leaves a hole behind, the other makes off with it, but same difference.

There doesn’t seem much point debating whether Dali was a dollar-clutching scumbag. But life isn’t obliged to hand us easy answers, and he was also (at times) a superlative artist. While James was a longstanding supporter of Surrealism and an interesting figure in his own right, not just a standard toff looking for the latest thing. And Meret Oppenheim, Surrealist par excellence, made limited-edition luxury gloves. (If not until 1985.) Besides, in those days most painters got by either via patrons or by being wealthy themselves. We don’t live in this world and get to be untainted.

Besides, what’s often appealing about these themed shows isn’t the through line but the by-ways. Things which don’t necessarily belong here but, now they are in front of you, you’re glad of it. And the chance encounter seems the more Surreal way of going about things, better than rigidly inspecting the guest list. The show quotes Ingo Maurer: “Chance rules our lives, much more than intention.”

Case in point… When the architect Le Corbusier was claimed as Surrealist-influenced, first I felt they were clutching at straws early. But they went on to convince me. The painting by him, while good, was more post-Picasso than Surreal. (Albeit from the era where Picasso was saying he was Surreal.) But the sculpture ’Ozon III’ (1962, above) could have had Andre Breton pinning a medal to it for services to strangeness. It seems to simultaneously reduce the human body to a mechanism and turn it into a charming cartoon, with parity found between an arm and an ear. With its bizarre anthropomorphism there’s a strong sense of humour to it, and I didn’t know Le Corbusier even had one of those.

Should We Still Be Surreal?

“Surrealism”, the show says, “is still evolving. The torch has now been passed to contemporary artists and designers who dare to shake up the creative process.”

Well, we could argue about whether art is still evolving. But Surrealism didn’t re-use century-old devices, it sought out new methods to deal with the world they found themselves in, revelling in any upset this caused. Current-day artists shouldn’t be in thrall to it, they should be using it in the way it used primitive art, ruthlessly plundering it of anything that looked useful, discarding the rest.

As said over the ‘Dreamers Awake’ show at the White Cube, “contemporary artists are forever claiming they’re its inheritors, often on the basis of a hazy notion that once it was ‘edgy’ and now so are they. Does for example Sarah Lucas belong here? (Inasmuch as her tedious efforts belong anywhere.)” And you’d have to say much the same here, to the extent that Sarah Lucas does indeed show up again. But let’s do what we did then, and talk about the stuff that’s worth talking about.

From 1950 on, Piero Fornasetti was taking one face (the opera singer Line Cavalieri) and placing it on an endless succession of plates, each with some Surreal twist to the image. Though the twists are often ingenious, it’s the combination of form and content which makes it. We associate plates with mass production, with repetition, with conformity.

Anyway, the twin highlights of this more modern section of the show are chairs. Make of that what you will…

Danny Lane’s ’Etruscan Chair’ (1984, above) is made from the most industrial of materials, glass and steel tubing. Yet just by making them geometrically irregular he anthropomorphises it. Those are definitely eyes in its back, and I stood there waiting for it to scuttle off.

Alberto de Braud’s ’An Uncomfortable Place’ (1992, above) features what would be a regular chair frame, except that it’s erupting strange tendrils and knotty protuberances. Chairs we assume to be made from dead wood, but this seems to somehow have not just retained life but still be growing. (It’s actually bronze, it just looks like wood.)

And, in a sense, carpenters do to wood what society does to people, drain its essence, chop it into regulation size, make it into a usable commodity. Except the title leads us not to side with this rebellious chair but take on the perspective of the sitter. If you thought someone was about to sit on you, you’d automatically assume a more awkward shape, and this is the chair’s way of doing that. It’s reminiscent of the rebellious furniture of Svankmajer’s short film ‘The Apartment’.

That which you thought tamed and made orthodox may still surprise you, it may be a good point to end on. Except of course precisely what makes this a great art objects makes it literally impossible to use as a chair. It’s merely disguised as a functional work of design to make its point. This show’s full of things which are functionally useless. Some of which are just useless. While others enchant.

No comments:

Post a Comment