“In a world defined by territorial control Surrealism has demanded liberation and served artists as a tool in the struggle for political, social and personal freedoms.”

- Opening quote from the show

Not All Roads Lead From Paris

At the Arts Desk, Sarah Kent faulted this show for ”focusing on the periphery rather the epicentre… on followers rather than originators”, complaining about the lack of Ernst or Dali paintings. (She specifies paintings presumably because Dali has an art object here, and was too busy fulminating to spot the Ernst.)

Okay, critics don’t tend to be a preceptive bunch, so perhaps we shouldn’t fault her for not taking in all three words of the show title. But this centralist, hierarchical mindset is telling, and self-perpetuating. She and her fellows have hardly been starved of what they want. Let’s look at the London Tates alone… The Last Ernst show was ’91, perhaps a while ago. But the stultifyingly orthodox ’Surrrealism: Desire Unbound' was 01/02, then the uneasy mishmash ’Dali And Film’ ’in 07, then a (genuinely great) solo Miro show in ’11.

But this doesn’t stop with the Tate. Sarane Alexandrian’s book ’Surrealist Art’ dedicates a chapter to ’Surrealism Around The World', in which the only non-European country it visits is Japan. Small world, it seems.

In truth, Andre Breton, self-appointed Pope of Surrealism, has for too long dominated the story, with his slew of blessings and excommunications. Even if it weren’t so over-familiar, his is too narrow a map to navigate by. Following it in negative, taking up those he cast out, as the Hayward’s ’Undercover Surrealism’ did in ‘06, is better. But that still adheres to the same damn map, when it needs throwing out altogether.

Surrealism wasn’t a holy order or an exclusive members’ club. And it didn’t appear fully formed from a few lofty brows. Far from all roads leading from Paris it sprang up in a great many places, because the need for it was there. Despite its less-than-unblemished relations with colonialism in its Parisian guise, it was taken up by many anti-colonial groups. Senegalese artist Leopold Senghor commented “we accepted Surrealism as a means, but not as an end, as an ally, not as a master.” This show starts with an enlarged copy of a Surrealist map from 1929, centred on the Pacific and resizing nations according to their level of interest.

And the official reaction might suggest they were on to something. You lose track of the times you’re told of groups being suppressed, or artists getting banged up or going on the run. As one example, Eugenio Granell (more of whom anon) first fled Francoist Spain, then the Dominican Republic, this time to escape Stalinists, before settling in Puerto Rica.

What Do We Want? The Liberation Of Desire!

One of the many places the show discovers an enduring influence is the radical America of the Sixties. The Chicago Surrealist Group were involved in the well-known protests against the Democratic National Convention in ’68, while the Students For a Democratic Society journal ’Radical America’ put out a special issue called ’Surrealism In the Service of the Revolution’ (Jan. ’70, above). Another news-sheet was titled ’Surrealist Insurrections'.

This rekindled interest spurred old guard artist Jean Miro to respond with ’May ’68' (1968/73, above). It’s dominated by a huge splat of black paint as if hurled by a projectile. The subdued colours beneath suggest a nicer, more staid painting has had its graphic style wrested from it by those wild black strokes, one system yielding to another. As if he couldn’t agree with events readily enough, the artist had added his own handprint nine times.

And this is both more accurate and better to hear than the Surrealism we’re so often told of, aesthetes dreaming limpidly of other worlds while ignoring the one they’re actually in. But while Dada, or at least strands of Dada, lent itself easily to political agitation Surrealism has a more involved relationship. For example, Kamel el-Telmissany’s ’Wound’ (1940) is a hard-hitting visual image, but too straightforward, too readily comprehensible to be called Surrealist. (Despite being in this show.)

Let’s take something we can all agree looks the part. Helen Lunderberg’s ’Plant and Animal Analogies’ (1933/4, above). What are all these things doing within one frame? Both the title and those white dotted lines make it clear we should be looking for connections between these objects. As an example, the cut cherry on the left leads to a cutaway diagram of it.

But what about when it then connects to the belly of that torso? Well, analogies can suggest themselves. The cherry stone might suggest pregnancy, that would be a plant/animal analogy. Okay then, what about the line on the right? What sense can be made of that? Perhaps the white network it points to (veins?, nerves?) could be compared to the tree behind it. But no white lines there.

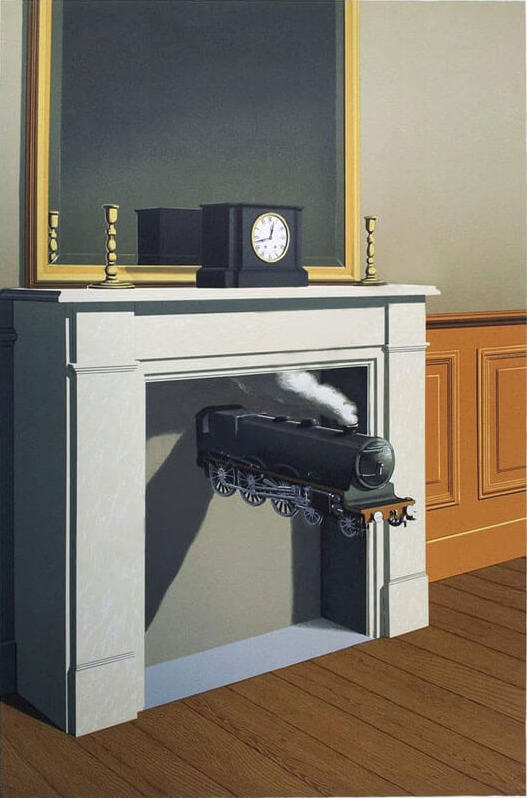

Next let’s look at something with the guidelines taken out - Magritte’s ’Time Transfixed’ (1938, above). Trains come out of tunnels, and hence apertures. And we associate trains with timetables, and hence time. (An association which may have been stronger back then.) So put a timepiece on top of the aperture of a fireplace and what do you expect to happen but summon a train? There’s the visual parallel between the front of the engine and face of the clock. It may also be a play on the way paintings are frozen while still depicting moving objects. (Echoed in the title, though Magritte himself disliked it.) It would have worked better with an actual model train, thrust through a hole cut into the canvas.

Except here it resolves a little too neatly. Surrealism’s primary aim, after all, is to disrupt. With Surrealism, the more you can reduce the cake back to the recipe, the less delicious it will taste. The show describes this rather well, as art which needs to “both suggest and subvert logical connections.” The game is to entice you into a maze of signs, then lose you there. Lunderberg’s the better Surrealist, even if Magritte’s more of a name.

Consequently, Surrealism can sometimes divide between the art that’s good and the art’s that it’s possible to write about, which can be a bit of a problem when writing about it. As I said after the DPG’s show on British Surrealism:

“Its credo should be ‘never knowingly understood’, and not just by the know-nothings of the dominant culture. It should be inexplicable even to Surrealists, with artists surprised by what springs from their own hands.”

A Hallucinatory Metamorphosis

Marcel Jean’s ’Surrealist Wardrobe’ (1941, above) features multiple apertures semi-obscuring a view. What we see of the view is pretty view-like, and it’s tempting to think that we should treat this as a kind of tantalising peepshow onto freedom. If we can’t cross this barrier we should at least look through it as much as we can, into the bucolic delights of whatever enchanted Narnia that lies beyond. The wooden blockade might be said to stand for dominant ideology, the wardrobe the restrictive roles thrust upon the self by social conformity, or some such. Hanging it in the very first room might subliminally push you towards this reading, as we’re here to see what lies ahead.

However, despite the title it resembles no actual wardrobe. It’a a crazy accumulation of apertures, some lying recursively inside others, and including letterboxes - which don’t get added to wardrobes much. As seen in the recent Dorothea Tanning show, Surrealist art has apertures aplenty. Jean has gone as far as to screw actual metal plates around the key holes. Because they’re the point of the picture, more so than the view beyond. This is the liminal place Surrealism occupies, between dream and waking, conscious and unconscious. It stands at the interchange, and invites us to stand there too.

Similarly, the Portuguese artist Artur Cruzeiro Seixas made the assemblage ’No Longer Looking At The Earth, But Keeping Feet Firmly On the Ground’ (1953, above). A buffalo hoof combined with what we take for a bird’s head, one of many ‘spliced’ Surrealist assemblages which stick together two seemingly irreconcilable objects. Yet we shouldn’t see this as a sight to stir our contemplation, like the proverbial Buddhist listening to the sound of one hand clapping.

Again, we should say “this is us”. We are not integral creatures, we are wing and hoof. We are these things even if they contradict, feet on the ground the same time as head in the clouds. And the fact that these elements are spliced, not bolt-ons added to a more recognisable body, emphasises this.

If the alter ego and animal familiar were frequent Surrealist devices, this is part of the reason why. Birds are commonly employed, perhaps most famously with Ernst’s Loplop. For they allow the bird part of us to stretch away as the rest of us stays moored, at least conceptually. So you’d scarcely need to be an initiate to guess that Leonora Carrington’s ’Self-Portrait’ (1937/8, above) is a triple self-portrait. Her mane of hair, her pointing hand, the anthropomorphised face on the hyaena don’t hide any of this.

Though more interesting is the white horse, the way it’s in two places. The rocking horse inside the room, overlapping with Carrington-as-herself, and the wild horse running free outside the window even have identical poses. To return to Jean’s metaphor, only her familiar can both be in the wardrobe and go to the lands beyond. And it can only do it by being both sides of the barrier at the same time.

So, you may be asking, just how does this perspective translate to radical politics?

Hear the title of Mayo’s ’Baton Blows’ (1937), then get told by the indicia that it was a time of great civil unrest and (its inevitable corollary) police violence in his home city Cairo, and you immediately build a mental picture. But it’s probably not of the picture he’s painted (below).

There’s a picture plane, with trees on a distant horizon line. But the figures are pushed right up into the foreground, like they haven’t noticed. And rather than ordering themselves into two opposed camps the figures are inter-twisted irresolvably. To the point they don’t look like they’ll ever be separable again. If they’re differentiated it’s into pink versus off-white, with nothing to clue us in which side is which. Mayo’s signature is in the bottom right corner, just below the lolling tongue of one collapsed figure. Just like Turner turned his back on narrative painting to present just the storm, Mayo shows us just the battle.

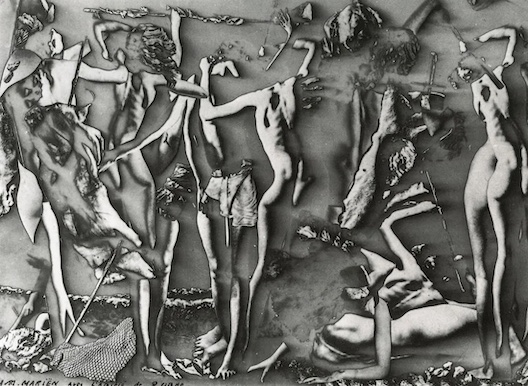

And this isn’t unusual. Raoul Ubac’s exposed print ’The Battle of the Amazons’ (1939, above) is a similar composition. It’s if anything still more ambiguous. Composed of cut-up photos, re-shot and over-exposed, are its figures fighting one another, or merging together? (Some accounts claim the original photos were all of the same model.) While the Mosambiquan artist Malangatana Ngewnya’s ‘Untitled’ (1967) arguably goes further in absolutely filling the foreground, with barely a scrap of negative space.

Lee Miller’s 1941 photo of a fallen, damaged statue (above) is part of her series ’Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire’. It could perhaps be seen as war propaganda, an inventory of cultural treasures the Nazis cruelly destroyed. Yet in that case why would it be titled ’Revenge On Culture’?

Roland Penrose, quoted in the show, says Surrealism aims “to provoke a hallucinatory metamorphosis”. And, as much as Dadaism, Surrealism was born of war. Which does a very similar thing, blasting holes in accepting norms, literally and metaphorically turning things over. If anti-fascist, they were not necessarily anti-war. War could be seen as cousin to revolution, a kind of liberating catharsis, which allows art to rebel against its originally programmed purpose, to become something new. It plays the same role in the real world as the collage artist’s bond-slipping scissors do for workaday images.

’The Guide’ (1862, above) by Cuban artist Herve Telemaque, combines a diagrammatic style with elongated forms. Until it’s quite hard to work out what is an object and what are motion lines. With the result that there’s something slightly anthropomorphised about those shapes. With an arrow pointing off the canvas it’s about as near to animation as a canvas can be. Other shapes are roughly sketched in, perhaps emerging or fading. Art, even a painting, should not be seen as a fixed thing. Metamorphosis, transformation, these are not incidents but the inherent state of things.

The Charged Object Strikes Again!

Bluffer’s tip! Should you want to sound like you know something about Surrealism, don’t say sagely “mmm, the dream.” (And still less “the fish”.) Instead, use “ahh, the charged object.” Regular readers, should they exist, will remember me waxing lyrical on this after both ’British Surrealism’ and the Academy’s ‘Dail Duchamp‘ show. And, as the show reminds us, 1936 saw the Surrealist Exhibition Of Objects.

The show has the smarts to place two objects next to one another - Joyce Mansour’s ’Nasty Object’ (1965/9) against Dorothea Tanning’s ’Pincushion To Serve As Fetish’ (1965). Mansour has driven nails and other shards of metal into a sponge ball, until the ball itself invisible is no longer visible. While Tanning called hers “a superstitious if not actually shamanistic object, and yet to my mind it’s not so far from a pincushion.” , Both recall the way primitive magic works, where fetishes must be pierced for their power to be released. Art is taken as having transformative powers, but these will only work for those who interact with it.

An over-emphasis on painting is one of the many ways Surrealism gets misrepresented and disempowered. Film and photography weren’t just present, there were arguably *more* useful because we so readily ‘accept’ them, take them for real. Happily, the show makes efforts to include both.

Take for example the short from Czech film-maker Jan Svankmajer, ’The Flat’ (1968, still above), which brings these elements together. The indicia, and seemingly every review, seemed determined to read the Prague Spring into this, without ever specifying how that’s supposed to work. In fact, I don’t think it does.

A while back, looking at Sartre’s novel ‘The Age Of Reason’, we found that for the lead character to be free his possessions must become “no longer his accomplices” but “anonymous objects... mere utensils”. Things must be seen as things, tools for use, make sentimental attachments with them and they will tie you down.

Surrealism could scarcely take a more opposite view, its perspective comes from recognising objects as entities; to be recognised, to enter into accordances with, the most humble modern objects seen as possessing spirits. Svankmajer’s hapless protagonist attempts to use a bed just as a bed, a door just as a door, a tap a tap. Naturally, they take offence and resist. If we do not see such objects as charged things, if we don’t make connections to them, their magic will work not for but against us.

But there’s an exacerbating factor at work. As with Sartre, our protagonist is youthful, his life still for him to make. And this is demonstrated through the furniture of a rented room. These things are not his, but strangers to him. By the end he’s able to sign his name beneath the “was here” graffiti of the previous tenants, and the accord is struck. (Ever gone back to a shared house and seen someone else living in your old room. Just as you did, but them? There’s a strangeness to it like little else.)

We might wonder what this is all about. And ask, if we’re to be interested in Surrealism, do we now need to believe beds are sentient? No small part of the answer is that it brings artistic benefits. As the Swiss-American artist Kurt Seligmann commented:

“Magic philosophy teaches that the universe is one, that every phenomenon in the world of matter and of ideas obeys the one law which co-ordinates the All. Such doctrine sounds like a program for the painter: is it not his task to shape into a perfect unity within his canvas the variety of depicted forms?” (NB Seligmann is in the show, but not this quote.)

But also, when decrying the consensus reality the Western world has built around it, its natural to look for counter-models. Chesterton, not much of a Surrealist in the main, said: “The whole object of travel is not to set foot on foreign land; it is at last to set foot on one's own country as a foreign land." Your aim is always to look at what you were always looking at, just from a new angle.

And Modernist artists had already used the form of tribal art as a means to counter Renaissance conventions, most famously with Picasso and his African masks. To now incorporate the content, as part of a much wider programme of disruption, seemed a natural next step. And Freud, as ever their go-to guide, yet again seemed to have written a handbook for this.

In ’Objects That Can Speak For Themselves’, Chris Fite-Wassilak identifies two poles for this kind of animism in art. At one end, an object’s “power was, for the surrealists, more like a mirror – one that could reflect the hidden, interior mind of the person who chose that object.” This way, objects became akin to Rorschach tests, the point is not the thing itself but the reactions it stirs in you. (The alert reader will have spotted this essentially re-objectifies objects, turns them back into our servants. The non-alert reader will have spotted the same thing.)

Then at the opposite pole he places Paul Nash, who had his own Tate show, where the artist can only borrow objects which retain their inscrutability. (“Nash’s attitude is one of a more direct animism, where the object isn’t a reflection of the artist, but might be placed in a position to speak for itself, as it were.”)

You could probably go on and on with this. But best not to…

Style As Means

Instead let’s ask, how do you get that over? Surrealism wasn’t a style in art, like Cubism or Constructivism. It was first and foremost an approach, one that didn’t necessarily require artistic means of expression at all. And when it did, that’s all they were - means. Artists who don’t have remotely similar styles can be - and are - Surreal. It’s hard to think of another art movement where the works could be so stylistically different as they are here, and yet still belong together.

Danish artist Wilhelm Freddie is represented by ’My Wife Looks At The Petrol Engine, The Dog Looks At Me’ (1940, above). And that flatly descriptive title carries over into the work. Each brick and coloured ball is diligently detailed, then that deadpan style carried over into the strange dog creature. It’s not presented fantastically, but as if it all makes sense to someone, even if that person isn’t us. From the ’Dali Duchamp’ show, we saw Dali did just this. And there’s a choice quote from him here, about “materialising… with maximum tangible reality, ideas and fantasies of a delirious character.”

While ’The Sea’ (1929, above) by Japanese painter Harue Koga combines naturalistic styles and pseudo-scientific cutaway diagrams. It’s a collage which looks like it should be resolvable, but isn’t. The cutaways suggest we should see things two-dimensionally, we’re not looking back but down. In which case the submarine’s directly beneath that sailboat, but then the bird’s about the same size.

And where does the woman swimmer fit in either way? Unless she’s a colossus, we’re supposed to see her in terms of pictorial depth. Perhaps she, and the right quarter of the frame, might be a separate unit from the rest? That would explain why the sea’s at two levels, not something it commonly does. But then they’re made to overlap. And those horizontal-striped fish still look suspiciously large. And, after the original confusion over the horizon line, why does the lighthouse float just above it? It’s like one of those sentences which obey all grammatical rules while making no sense.

But conversely, the Haitian Hector Hyppoliyte’s ’Ogun Feray’ (c.1945, above) could scarcely be in any more a naive style. It doesn’t dramatise the objects so much as flatten the human figure, turns him into an object as much as them. Until there’s such an equivalence it scarcely seems surprising they’ll jump up and dance the way they’re doing.

While New Zealander Len Lye took a similar approach, but with a film - ’Tusalava’ (1929, still above). Initially we could just be watching the filmstrip run past the projector. First, abstract shapes emerge. And it’s remarkable how soon we start to anthropomorphise these. (With me, literally a few seconds in.) These turn into cellular creatures, then develop into totemic forms, as if up to now they’ve been gestating. Crucially these forms aren’t articulated, they don’t ‘come alive’ in the conventional sense, they stay as moving shapes. But it simply doesn’t feel that way to watch.

And much of this comes from Lye using the warm imperfections of filmstrip, the graininess, the blotches and streaks. The shapes pulse with life in a way smooth vector art would not.

So Surrealist art had to occupy one pole or the other - hyper-real or naive? Not really. Eugenio Granell’s ’The Pi Bird’s Night Flight’ (1952, above) is sharp and realised, but iconic in look. The bird creature is laid out in two dimensions, against a flat black background. Does such a bird really exist? No use asking me. But even if it does, it’s immediately clear that Granell isn’t interested in capturing the outer look but it’s spirit, as if enlisting it as some form of totem.

Romance Is Dead?

Modernism was intended as a reaction against Romanticism. It’s something which Dada would simply have spat at. (Brecht hung banners behind his plays stating “Don’t stare so Romantically”.) But Surrealism’s relationship is more complicated. At its worst it simply inherited. Romanticism’s reaction to the Enlightenment, a headlong rush to escape the confines of reason, had at the time been something current. But Surrealism could pick up on this many generations later as if it was still a live debate. Which it did by simply transferring the sublime from out there, in nature, to in here, the human mind. Which, as we’ve seen before, wasn’t even that much of a switch. But what about when it was at its best?

The Italian artist Enrico Baj created ’Body Snatcher in Switzerland’ (1959, above) by taking an existing kitsch Romantic landscape and painting that monstrous monolith figure over it, part graffiti, part provocative cartoon, part Lovecraftian clash of reality systems. Note how its bulging lower regions hover over that poor peasant woman. It works partly by taking Romanticism at its own game and upping it. For Romanticism often depicted nature just this way, dark, animate, inscrutably strange.

While Remedois Varo’s 'The Flight’ (1960, above) took the familiar Romantic image of a figure ascending the heights of remote, craggy, cloud-strewn peaks and simply added a female figure to the mix. We are, I think, supposed to see them a sailing on a cloud boat, a brilliantly delirious notion. (It’s part of a triptych representing her, all done in that sharply precise illustrational style, belying the strangeness of the subject matter, and all superb.)

’Nudes’ (1945, above) by Egyptian artist Samir Rafii of course dates from the end of the war, into which others have read significance. But there’s a timeless ‘folk apocalypse’ feeling to this work that’s more Bosch-like. We’re used to art that shows the sombreness of the aftermath of a massacre. Just as we’re used to art that presents the revenge of nature. But, well, not really this…

All the figures are, I think, female. And women are of course often victims of war. Except here I think they’re victims of a nature which is itself feminised. The hunting birds set us up to see the figures as victims of the trees. In Romanticism Nature is seen in terms of the sublime; which is, by definition, depersonalised, a remote and overpowering force, the storm that tosses your boat without noticing you’re there. Here it is anthropomorphised and monsterised simultaneously.

And that foreground tree, all spikily protruding branches, isn’t just pinning that poor foreground figure. It seems to replace her upper half, that hairy birds’ nest the nearest thing to a head, as if some symbiotic creature. It also seems to echo her pubic hair, making another connection. It’s as if one part of our nature was at war with another, to the point of massacre. (Ignorant of Arab names, with no many female figures, I first assumed this must be by a female artist. Wrongly, as it happens.)

Discovery Not Invention

Surrealism’s sometimes presented as individualised, furiously dreaming Bohemians, like prospectors of their own private subconscious, hoping to come back up with some artistic gold. In fact it was always a group effort. The show acknowledges this throughout, talking of ‘convergence points’ and quoting Simone Breton on “images unimaginable by one mind alone.”

Sadly then, despite it being so related a concept, automatism (creating art without conscious direction) becomes an afterthought. Literally so, as it’s mostly consigned to the last room. And it mostly focuses on automatist techniques, as if it was all a means to an end, not a source of artworks in itself. Whereas, to quote Michael Richardson:

“The real importance of automatism lay in the fact that it led to a different relation between the artist and the creative act. Where the artist had traditionally been seen as someone who invents a personal world, bringing into being something unique to his own 'genius', the surrealists conceived themselves as explorers and researchers rather than 'artist' in the traditional sense and it was discovery rather than invention that became crucial for them.”

At the least it should be said that, much as with the debate over abstract art, the notions weren’t rigidly exclusionary. The artist could slip between both, as they chose.

Due to the dearth of good examples on show here, we need to break protocol and look at a work which appeared in an earlier post. Which is not even hung in the automatist section. Gordon Onslow Ford’s ’A Present For the Past’ (1947, above) appeared in the DPG’s ‘British Surrealism’ exhibition. After which I said: “With its birds and that central egg form, it doesn’t seem composed so much as grown…. creativity doesn’t work by logical progression but is more akin to morphogenesis.” As the artist said himself of painting without a plan, “in venturing into the inner worlds, nothing was lost.”

(NB There is a flaw running right through all of the above. To present Surrealism as a cohesive political and philosophical movement requires a whole lot of forcing the pieces. This was a movement, not a regiment. With a cast list so culturally and geographically disparate, it’s better seen as sketching in some of the through lines.)

This show is simultaneously uneven and overwhelming. There are misfires, and works which don’t even belong here. But there’s a high hit rate, higher than I could possibly cover. Much like Post-war Modern’ at the Barbican, I was struck between the eyes, again and again, by artists I’d no prior knowledge of. With the double-whack of these two shows, gallery-going has resumed in earnest!

No comments:

Post a Comment