“Scavenged materials were fashioned into futuristic bodies. Wounded, collapsed and shattered forms were countered with primeval goddess imagery that celebrated fertility and rebirth; ambiguously gendered bodies throb with mutant energy.”

-from the programme

The New Brutalism

A full stop may seem an unusual way for an exhibition to start. Yet this one does, and it proves the very best place. John Latham’s ’Full Stop’ (1961), also on a version of the poster, is on a quite monumental scale for so simple a work. It might initially seem asking to be compared to Malevich’s Black Square.

Except that seemed more a symbol, leading to thoughts of eternity and mortality. Even without the title, this would seem more a sign. It’s spray-painted, presumably using a stencil. And if you blew up a typewritten mark to that size, you’d probably get something similar, discernible yet faintly smudged. And a sign has to be of something…

The artist Frank Auerbach said of the immediate postwar era: “There was a curious feeling of liberty about, because everyone… had escaped death in some way.” Seen this way, you’re looking at the full stop from behind, from a future you never expected to have. And the liberty this leads to is of course is a heady liberty, knowing your continuing existence is down to little more than chance. But that in itself wouldn’t have lasted for the next twenty years.

After the Tate’s ‘All Too Human’ show, I pointed out that in Leon Kossoff’s art “London is monumental but at the same time turbulent, ceaselessly overwriting itself.” This could well have originally been rooted in the dropping bombs which rewrote (or de-wrote) the landscape overnight. But his art also refers to post-war developments, quite literally so. In many ways it’s in antithesis to a London marked by bomb sites for successive decades, a London which never really got over the War. His is a London which effectively never stands still.

For this initial heady rush soon combined with pressing political questions. There was a widespread feeling against simply going back to the world as it was before the war, the world which after all had led to the war. But then what to replace it with?

All the uneasy ambiguity so on show here comes from there. War had swept away all the old certainties, revealing an empty deck haunted by shadows. The tension over what might come next was both enthralling and anxiety-inducing. The show speaks of the iconic bomb site as a microcosm of the nation, representing “suffering, loss - but also hope.” The artist Franciszka Themerson talks of living in a “strange universe… [we] grope around, full of fears, pleasures, anxieties, violence, joys and tragedies, stupidities and anger.”

Sometimes the show tries too hard to make every piece fit, such as suggesting William Turnbull’s bronze reliefs resemble those bomb sites, which they don’t. But it is right to call his sculpted figures “totemic and brutalised, appearing as though… subject to forces beyond their control.” Much of what’s arresting about this art is its convulsive quality, as if this is what the times compelled to be made. (Notably, Turnbull was calling a work ’War Sculpture’ in 1956.)

Except all that overlooks a vital ingredient. It’s tempting to imagine art as arising solely out of its social conditions, in defiance of history or tradition. After all, Modernism’s credo was always “away with what was before, we start again”. Its method of progress is not evolutionary, but a series of definitive statements, with quite definite full stops.

But in truth, of course, it was always reacting against the art that had just happened. In the Guardian, Laura Cummings is more on the money. calling it “a magnificent antidote to the cultural triumphalism of the government-sponsored 1951 Festival of Britain.”

As seen in the exhibition ‘Out There: Our Post-War Public Art’, postwar reconstruction involved a large amount of public art being commissioned, as part of the new spirit of benevolent public institutions sometimes dubbed “Modernist Florence”. In this way, one form of Modernism became orthodox, even official.

It became claimable that this movement, associated with the post-war politics of planning and order, had robbed art of its mystery, made it into something orthodox and reassuring, ultimately tame. Was this a fair assessment? Not really, no. But art history has seen more baseless takes.

So the International Style epitomised by Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth became the throned King who needed toppling. If their art was smooth and about pure form, we would be rough and abrasive. If they used stone and polished wood, we’d get our materials from the scrapyard. (Often literally.) No artwork was thought worth its salt unless it looked left out in the weather. Above all, if they were optimistic and celebratory, we’d parade our anxieties.

In short, these guys were the punks! Unafraid to shock, disdainful of the easy certainties of utopianism, wired with negative energy. This came to be dubbed the New Brutalism, a term coined by Alison and Peter Smithson, with Reyner Banham. (Yes it took three people to come up with a two-word name, perhaps due to postwar job creation schemes.)

Lynn Chadwick’s sculpture ’The Seasons’ (1956, above) is a handy visualisation of this. “Designed”, say the indicia, “as an opposition between an angular pyramid shape and a branch-like form alive with tendrils and shoots.” The pyramid looks a pure form, but acts as a shield for what’s behind it - something more monstrous precisely because it seems to writhe with life. Chadwick was turning the seasons, from festive Spring to bleak Winter. (Disclaimer: Chadwick exhibited himself at the Festival of Britain, and won some public commissions. But then punk bands sometimes got on ’Top of the Pops’.)

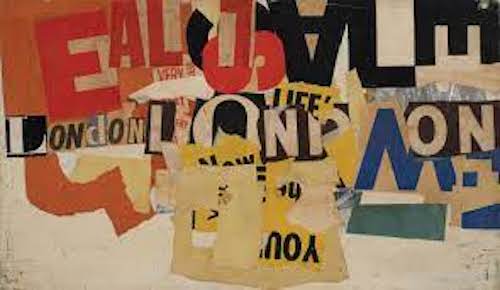

And it’s in these two coming together that the magic happens. In the room ’Choreography of the Street’, the show has the wit to present photos of the urban landscape against the collages and print designs of Eduardo Paolozzi and Robyn Denny. Check out, for example Denny’s ’Austen Reed Maquette’ (1958) next to Roger Mayne’s ’God Save The Queen (Hampden Crescent, Paddington)’ (1957, both above). The frenzy of cut-out letters, in part shouting ‘LONDON NOW’, is both bookend and companion to the urban dereliction of two kids outside a shuttered and graffiti’d building. Bizarrely, it’s such a punk record sleeve in the making it’s even been named for it. Just like the Seventies, life seems to flit between vivid dreams and harsh realities.

Chadwick’s ’The Fisheater’ (1951), with its wire metal frame, looks like a rebellion against the stone-block materiality of Moore’s sculpture. As the title suggests this is not a bird which flies free and sings from the sheer pleasure of it. This is a remorseless hunting machine, it’s beaky head like an arrow tip. “Fisheater” is what fish would call birds, had they the language.

And Elizabeth Frank’s ’Harbinger Birds’ (1960/1, example above) possibly push this along further. They look like pieces of scrap metal who have somehow sported legs and are walking. Those legs are bent backwards but, with some human proportion, seem placed between bird and man. The show points out that in the war Frank was both “exposed to air raids” and saw crashed planes. The name recalls the way birds were often seen as omens or portents, while suggesting more like this will come.

While Nigel Henderson’s collage ’The Growth of Plant Forms’ (1956, above) takes a 2D view which should render its subject familiar and diagrammatic, something reassuringly explained in a science textbook. Instead it makes life itself seem strangle and ungraspable. These last three works, it would be tempting to see them as using nature to stand for our ids, possessing inescapably savage truths. But it’s more than that. All three works seem so monstrous because they are so unparsable, so irreducible to our reason. The savage is at the same time brutally simple and utterly strange, even at the very same time that he is a part of us.

The Savage Machine

And the combination of the savage and the machine recurs. In one sense a machine is savage, it has an animal purposefulness, it acts out its nature with no need of morality. Lawrence Alloway called this era ‘Britain’s New Iron Age’, and described Paolozzi’s sculpture as “hieratic as a mummy but as wild as a drugstore”. A splendid phrase which could be applied more widely. Notably, perhaps wary of past problems, there’s no particular ‘primitive’ place or time which is venerated.

The Paolozzi sculptures are all excellent, of course, looking like a budget British version of ’Terminator’, and all the better for it. But ’St. Sebastian 4’ (1957, above) is the most captivating, because it has the most familiar human features. Yet though we recognise and respond to these, they come through the conventions of child art - an oversize round head, a block of a torso below which juts two legs. (The work is ‘signed’, titled and dated via a metal plate screwed into its base.)

John McHale’s ’First Contact’ (1958, above) is a primitivist depiction of a family watching TV. At a time when TVs were housed in great cumbersome boxes, McHale gives us a screen that floats, a kind of apparition. And for all its avowed crudity it’s remarkable how it captures in a 2D image how these figures are looking at that rectangle. The thick black line around the screen then joins the figure on the left and passes to the rest of the family. It’s as if its prolonged cathode-ray influence has turned this family into these cyborg beings. Having stared into the machine so long they have become machines themselves.

Yet while there’s something highly Dada about this, it’s a world away from another Dada image of a consuming family, Heartfields’ incandescently furious ‘Hurrah! Der Butter Ist Alle’. Both have humour in their own way, but McHale’s is impish, with its tomato slices for eyes, and light fittings for mouths. In its sensibility, it’s Pop. Might the mass media change us, down to your very marrow? Then bring it on! We were due a change.

McHale had said “we can extend our psychic mobility. We can telescope life, move through history span the world.” ITV was just two years old, a choice between channels then still a novelty. Of course, in our era of Celebrity Big Brother, he may seem as idealised as Moore.

Let’s compare Avinash Chandra’s ’Early Figures’ (1961) to another classic work of Modernism, Fernand Leger’s ‘Three Women’ (1921/2). Leger proposes a unity between the human figure and machine, to the extent they can be depicted the same way. Which is bright and smooth surfaces, as if the whole world were made from chrome. There’s an exuberance to his art which is almost child-like. It almost recalls the anthropomorphised machines of children’s books and cartoons.

Whereas Chandra’s isn’t some machine fresh out of the factory, with it’s shop-bought colours, but battle-worn. The Leger might have even come to look like this, had it been left out in the weather those intervening years. And the figures and machine parts morph, the circles of faces echoed in cogs, forming an incomprehensible cluster of parts. It’s hard to avoid returning to Alloway’s description of both hieratic and wild. It recalls that von Daniken trope beloved of science fiction films, where ancient art is found containing modern technology.

Franciszka Themerson’s ’Eleven Persons And One Donkey Moving Forwards’ (1947, above) is arguably titled back to front. It’s that sweep of motion across the frame which you notice first, the cartoonishly reductive figures almost there merely to instance that motion. Jewish, Themerson had fled Nazi-occupied Europe, losing almost all her family. The addition of a donkey recalls the Bible, which makes the story a timeless one. Notably the figures aren’t moving from or two anywhere, they’re just in motion, as if demonstrating an immutable law of life.

Then, in 1959, she painted ’How Slow Life Is And How Violent Hope’ (1959, above), effectively a counter to the earlier work. The feet incline forwards but the vast, bell-shaped bodies, and the whole style of the work suggest otherwise. The figures are effectively mired in thickly encrusted oil, gouged lines sometimes defining forms and at others cutting across them. These almost shapeless things will have to drag the dead weight of themselves if they are ever to move.

…And How Are Things At Home?

After the Tate’s ‘All Too Human’ show I pointed out that Walter Sickert, while a forerunner to this era, was “only a precursor [because] he paints scenes” - and domestic scenes at that! McHale for example depicts what would by rights be a family lounge, but eliminates everything bar what interests him – the family and the TV screen. Yet elsewhere the front room was becoming inviting territory all over again. A focus on the domestic might ostensibly seem a retreat from the social anxieties that gave this era its tension and energy. In fact, anything but…

Jean Cooke and John Bratby were both artists and both in troubled marriages. To each other, as it happens. The self-portrait as statement is scarcely an innovation of this era. Nevertheless, it’s notable what lengths Bratby goes to with ’Self-Portrait In a Mirror’ (1957). Self-portraits are normally done in a mirror, but Bratby not only paints himself painting, he frames the mirror within the picture frame, adds shimmer to it, and then places bottles before it. This is assertive, he’s almost literally a self-made man. He looks ensconced at home, doing what he does where he belongs.

While in Cooke’s ’Mad Self-Portrait’ (1954, above) her white top accentuates her black eye, and her stiff gaze adds to the uncomfortable viewing. The show stops short of saying he gave her that eye, perhaps that’s not known. But he pathologically limited her painting time (her work is much smaller than his), sometimes destroyed her art and was known to be violent to her.

It’s the one point in the show when we see the Fifties we think we know, the one that preceded the Sixties. We want feminism to come along and rescue her, while knowing we are years too early for that. The only hint of escape is that open window.

Bratby is, by now, not easy for us to look with favour upon. But out of their unequal race, the most interesting work is his. ‘Jean and Still-Life In Front Of a Window’ (1954). The table is raked like a piece of primitive art, then crammed with goods. Many in such brilliant white they look to illuminate the room. The labels Tale & Lye, Corn Flakes and Shredded Wheat have been added in obsessive detail.

1954 was the year rationing finally ended in Britain, and this work seems to come from a mind overwhelmed by consumer choice. These goods surely didn’t just come from the corner shop, but arrived from some higher realm. In fact they seem to exude more life than the distanced figure. Who, a domestic nude, seems to deliberately clash conventions with the emerging Pop movement.

While Bill Brandt’s photographs take an entirely different look at domestic life. He moved away from photo-journalism on, the show tells us with some relish, VE Day. For a work like ‘Nude, Micheldever, Hampshire’ (1948) he used a new wide-angle camera. The expanded depth of field which results is accentuated by the figure’s outstretched arm, and open-palmed invitation. ‘Inner’ notably doubles as a description for the domestic and the world of the mind, and Brandt gives us a domestic which isn’t confined or parochial, but a rabbit hole to fall into and find a world of otherness.

With the nudity of the figure and clean staging it is, admittedly, a re-invention of Surrealism nearly three decades later. The mysteriously semi-open door is a common Surrealist device, widely found in the work of Dorothea Tanning (as we saw). But it’s a re-invention that gets Surrealism, that doesn’t think it’s about day-glo outrages so much as defamiliarising the everyday.

Colour Coming off the Ration

The show includes a poster for the Whitechapel Gallery’s celebrated ’This Is Tomorrow’ exhibition in 1956, featuring Richard Hamilton’s celebrated collage ’Just What is It That Takes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?’ (above). Yet those bright colours of mass production, which seem so central to the work, are reduced to black-and-white, losing much of the detail in the process. To see the colour original, you had to see the show. Rationing had ended, if only just. But it does still seem a snapshot of austerity Britain.

Then you come across Gillian Ayers’ ’Break-off’ (1961, above). It looks completely spontaneous, like a coloured doodle blown up to giant size, losing nothing of its immediacy. The elongated proportions are effective in giving it a sense of motion. It may well be influenced by American Abstract Expressionism, but feels quite un-angsty or ponderously timeless. In fact it’s immediate and positively rhapsodic!

With Hamilton a small… if pitifully small degree of the original still comes through. You’d see the poster and know what sort of work it was. While with Ayers colour is all! Sometimes a painting seems to come along and reacquaint you with colour - bright pinks, deep oranges, full blacks, as if they’d only just been invented and so needed demonstrating. It’s a fantastic work and falls within the two-decade remit of the title. But the show’s right to say it. This is one era ending, and another thing beginning…

I am a little more undecided over which side of the wire Alan Davie belongs, perhaps because he has less of that immediate impact. The two works of his on show are ’Creation of Eve’ (1956, above) and ’Marriage Feast, or Creation of Man’ (1957). And the repeat use of ‘creation’, as a verb, is significant. A painting is static by definition, and yet Davie seems able to defy that. These works feel incohate as your eye is pulled around them, incapable of staying fixed. Like Pollock of the same era they seem to crackle with energy.

Combined with which… Unlike Pollock, they incorporate recognisable elements. The revolt against representation was the fight the American Ab Exers made theirs, but that didn’t necessarily translate to everyone who came after. And when combined with their gargantuan size this cannot help but you think of symbolic or narrative art, of murals or reliefs. It’s a thought that you can never either confirm or deny, which hangs about in your mind. In what would seem one of the defining artistic questions of this era, divided into such rigid camps that it could literally lead to fistfights, Davie instead dances in the no-man’s land. It’s this indeterminacy, this thing-betweenness, which becomes his selling point.

(Pop Art should, were there any logic in the world, prove a similar break point. But, as seen after the Pallant House show, British Pop Art was a wilfully self-contradictory beast not as reducible as its younger American sibling. Paolozzi, for one, absolutely belongs here.)

What Weird Flowers Grew

It may feel like faulting the show for a virtue to say it’s too comprehensive. But, with no less than forty-eight artists, at points it is. Two decades of art can’t be compressed into two floors of a gallery. For example Victor Pasmore and his Objective Geometry compatriots (sometimes confusingly titled Constructivists) seem outside the scope of this narrative, and would have been better slotted in elsewhere.

(Or just forgotten. Truth to tell, their art wasn’t great. It looks like they deduced, quite correctly, that the gallery circuit was a hermetic world. But then assumed the problem somehow lay with the materials. So ditch the fancy oils for perspex and sheet metal, and the masses would be reached. They weren’t.)

I was born the year after this exhibition ends. Which does seem the cusp of a change. The baby boomer generation, for example, officially ended in 1964. And rather than playing in any bomb sites, my childhood memories are of new housing estates springing up. And naturally, you cannot be anything other than fascinated by what you just missed.

On the other hand, it’s more than just me! What weird flowers grew from those bomb sites! The programme talks of “an art more vital and distinctive than has tended to be recognised”. Which if anything undersells it. The truth is that Britain - yes, Britain! - in the Fifties - yes, the Fifties! - was a high-water-mark of Modernist art.

But is it as impressive as American Abstract Expressionism, the cross-Atlantic art of this era, as seen in the Royal Academy show? Yes, I think it is. But it’s as British as that was American, less grand and ostentatious, more the made-do-and-mend Modernism of ’Blue Peter’ viewers, but just as vital - if not more so.

Name after name I’d simply not come across before, and I’m always seeking out this stuff. Laura Cummings’ Guardian review described Franciszka Themerson as a “discovery”, and Matthew Holman in the Arts Newspaper “a revelation”, so it isn’t all my ignorance.

You can’t help but wonder, after this gallery’s own recent Dubuffet show, which has much in common with here - if he’d been unfortunate enough to be born British, would he have been memory holed too? How could this rich history have been so forgotten?

Partly it doesn’t fit our standard narrative of a Fifties in cultural stasis, when everyone just patiently awaited the Sixties to come around so something could happen, then discovered the actual Sixties weren’t showing up till the mid-decade. We imagine the grey diet, the boiled cabbage and spuds, set the flavour for everything else. And once set these narratives become self-replicating, you don’t lift the lid on boxes you imagine to be empty. So there’s a special buzz to seeing one of Auerbach’s vast and sweeping encrustations of paint, simultaneously monumental and energised, to discover it’s tiled ’Willesden Junction, Early Morning’ (1962).

And partly because it’s so many of these artists weren’t British, as so many then would have narrowly defined it. Themerson’s story, however tragic, is far from uncommon, and the show is soon using the line “another refugee from Nazism”. While others came from what had recently been, or in many cases still were, the colonies.

On one level, there’s an absurdity to calling these guys outsiders. For one of the many old certainties to fall in this time was the supposed whiteness of Britain. This is demonstrated in the Shirley Baker’s photos of Sixties working-class Manchester, or the paintings of Eva Frankfurther such as ’West Indian Waitresses’ (1955, above), another of the poster images. The racist mind, perpetually in panic mode, will frame whiteness as something always just about to be lost, whatever era it is thinking of. But British history has been made by wave after wave of immigration, and the supposed integrity of our shores is simply a lie. No wonder Nigel Farage gets so fretful over beaches.

But more to the point, as ever, we should welcome these newcomers and hear what they have to say. It’s like Freud discovering the unconscious, and the Nazis then talking as if he’d invented it. Some may have been their bringing in continental Modernist traditions, as if concealed in their clothing. Burt mostly it was their situation, their sense of rootlessness, which led to their questioning. Their art was like a geiger counter, helpfully identifying every area of disquiet and unease. We needed these outsiders to really see us, to tell us about ourselves. Inevitably, not all welcomed the information.

Let’s take a slightly orthogonal example. For this whole era it was still illegal to be gay. And Francis Bacon’s ’Man in Blue’ series of 1954 (example above) is thought to stem from the covert world of gay liaisons at that time, like blind dating inside a spy movie.

But if that’s the work’s impetus, it scarcely tells us the whole story. The picture’s large and full of open space yet, dark and centring in on that bulky figure, feels claustrophobic - as ‘open’ as a spider’s web. The blurred face suggests anonymity, while at the same time adding to the thick air of menace. It’s a lightning rod for a repressive society, forever banishing things but then inevitably being drawn towards them.

In the admittedly unlikely event you’d like to read more of me ranting obsessively about… deep breath… Francis Bacon, Gustav Metzger, Eduardo Paolozzi, more Bacon plus some Lucien Freud, Leon Kossoff, Frank Auerbach, & Francis Newton Souza, then these are the links you need!

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment