Showing posts with label Psychedelic/ Acid Rock. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Psychedelic/ Acid Rock. Show all posts

Saturday, 14 December 2024

THE FIRST FESTIVE FIFTY! (AND ALSO THE TWENTY-FIFTH)

First drafts of history are never neat.

Take for example the first John Peel Festive Fifty. (Where listeners chose their favourite numbers.) Though ending the auspicious year of ’76, it contains not one single Punk track. Rather than ’Anarchy in the UK’ topping the list, its ’Stairway To Heaven’. It’s like one of those alt futures where we never escaped the servitude of the Roman Empire, except instead it’s listening to the guitar solo from ’Free Bird’.

Peel himself seemed less than impressed. The following year he decided he was picking all the tracks himself.

Perhaps more unexpectedly, listeners took the all-time request seriously. So the Beatles, the Stones, the Doors, Dylan and Hendrix all show up. (Tho’ nothing from before the Sixties.) And even when it does go Prog, the more bloated excesses (Rush, ELP) are happily absent. Yes creep in at No. 50 with ’And You And I’, probably one of their least proggy moments. (King Crimson may be the most curious absence.) For me, it was the more the AOR and classic rock stuff which was the obstacle. Jackson Browne and Poco were soon skipped.

But overall, as a snapshot of music up to ’76, it actually makes for a pretty good playlist. Sure its strange hearing ’No Woman No Cry’ segue into ’Supper’s Ready’. But not in a bad way.

Okay, British Punk was only just getting going at this point. The Pistols (for example) had released one single, ’Anarchy in the UK’. If it could conceivably have headered the list, there was no possibility of Punk packing it. But perhaps more conspicuous by their absence are the two biggest influences on British Punk.

You know the story of how, prior to forming the Buzzcocks, Shelley and Devoto took a trip to London to see the Pistols without having heard them? Because they played Stooges songs? And yet, you guessed it, no Stooges here. In fact American Punk appears only once, with Jonathan Richman’s ’Roadrunner’.

And mid-Sixties Powerpop, that shows up not at all. (‘My Generation’ made the 1979 and 1980 lists, but nothing in ’76.) Those lies John Lydon liked to tell, about British Punk supposedly having no influences (despite playing Stooges songs)… it looks like, at the time, people swallowed them wholesale.

As you might expect, subsequent years saw a slow decline in votes for ’Stairway to Heaven’ and a growth in Punk and Post-Punk. 1982 saw both an all-time and a year-only list, everything went year-only from then on.

Then, as a one-off for the momentous year of 2000, the all-time list was brought back. And it looks back as far as the original, some tracks make it from the early Nineties - roughly the same time lag.

But this time out its much more Eurocentric; almost half of ’76 had been American, this time precisely five Yanks make the cut. Despite many American acts not just being played but getting sessions on the show. And that with the simultaneous disappearance of Prog, which had always been a highly Europeanscene.

Remarkably, a mere three tracks from ’76 reappear, with two falling down the list. Take Hendrix’s ’All Along the Watchtower’, once no. 5, now to be found at no. 37. Dylan’s ’Visons Of Johanna’ fares similarly. Only Beefheart’s ’Big Eyed Beans From Venus’ moves up. And the early Seventies disappears almost entirely. (The Beefheart track is from ’72, but he was more a Sixties artist.)

But perhaps more significantly, a number of older tracks which could have been on the ’76 list suddenly show up. Tim Buckley’s ’Song To The Siren’ can perhaps be explained by This Mortal Coil’s cover, scoring much higher. But the Velvet Underground and Nick Drake? While the Beatles, who had been represented by three tracks, now switch to a new entry - ’I Am The Walrus’. (Still, surprisingly, no Stooges.)

Of course, you never hear music from the past directly. It cannot do other than come through the filter of the present. Perhaps, had there been another Festive Fifty two or three years earlier than ‘76, ’Tarkus’ and ’Tales From Topographic Oceans’ would have proudly reared their gatefold heads. Perhaps ’Kashmir’ and ’Supper’s Ready’ did suddenly sound bad in the context of the late Seventies, only to reach today and get good all over again.

But more, some songs go up like a firework and leaves a stain in the sky, while others have a slow-burning fuse. It takes a while for people to catch on to them.

Slightly bizarrely, this even takes in the world’s best-selling band. ’Walrus’ was one of the most radical-sounding Beatles songs. (Alongside ’Tomorrow Never Knows’, which stays inexplicably absent.)

Stories about the Velvets being shunned in their day get a little mythologised. In their time, their sound got slowly less extreme and their audience correspondingly increased. Plus their resurgence happened sooner than this might imply. Post-Punk openly owed them a debt, and by the time I was getting into music (early Eighties) they were already on the must-hear list. Had the all-time lists continued past ’82, I’d guessed they’d have shown up pretty soon.

Curiously, it was the much sweeter-sounding Folk-hued Nick Drake who took the slower lane. A press release from his own label proudly announced his new release wouldn’t be shifting any units either, but they were putting it out anyway because they liked it. After playing the track, Peel speculated about how Drake might feel about the change in response to his music.

Given which, supposing another all-time list could somehow be compiled now? Another quarter-century down the road?

Certainly, some things seem to take longer still to take. Krautrock’s era was roughly ’68 to ’75. But, despite being so big an influence on Post-Punk, it shows up not once. That would doubtless be different now. Maybe even… finally… the Stooges.

The premise of Peel’s show was the present. All-time lists stand out because they were a slightly counter-intuitive thing to do. Today, music seems to have gone the other way, with the past raked over at the expense of the present. There can be little left now that needs digging up, but still the slew of re-releases. So I’d expect a lot more leaning into the past and - most of all - much less of a difference in sound between bands of then and now.

Saturday, 20 April 2024

COUNTERING THE COUNTER CULTURE (THE ORIGINAL 'STAR TREK')

”The enemy from within – the enemy!”

- ’And the Children Shall Lead’

To Boldly Get Far Out

The voyages of the starship Enterprise began in 1966, the year John Savage has claimed youth culture exploded. And should anyone doubt it was a Sixties show in the way we think of them, and the hemlines alone weren’t convincing, show them the scene in ’Wink of an Eye’ where Kirk literally drinks the Kool-Aid.

Okay, officially it’s coffee. But the drink-me potion speeds him up to the point where he can see the aliens aboard the Enterprise, moving too fast to be visible to mere human perception. Who, most noticeably, don’t try to conquer him but convert him to their perspective.

Kirk’s view of slowed time is presented by Dutch angles, a visual conceit often employed to represent drugs or general derangement. And much of the episode’s appeal lies in seeing something once familiar rendered askew. (Beyond a brief intro, everything takes place on the familiar Enterprise sets.)

There’s a clear parallel between its time distortions and the contemporary fashion in psychedelic music for speeding up and slowing down sounds. Wikipedia cites as one of the main characteristic of the style as “Dechronicization” which “permits the drug user to move outside of conventional perceptions of time”, mimicking the effects of LSD (allegedly).

George Harrison said after first taking the stuff: “There was no way back after that. It showed you forwards and backwards and time stood still.” The aliens are even called the Scalosians, as if associated with musical scales. The episode itself becomes a little like dropping something in the coffee cup on the viewer’s armchair.

However unlike other adversaries (some of which we’ll move on to) the Scalosians themselves don’t represent the counter culture. In fact they’re a(nother) dying race who vampirically require humans. Accelerated time isn’t an enemy to be overcome so much as a setting for the story.

But then the Sixties themselves seemed an accelerated blur, something hard to take in at the time. (A point made by Darren in The M0vie Blog.) This wasn’t just the tempo of music or the rapid spread of the counter culture, though it included both those things. Rather than anything, it was everything. Art, politics, technology... the world seemed to be changing right under you.

Hindsight can have a flattening effect. The Futurists, the art movement operating before the First World War, boldly asserted in their manifesto “Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.” But by the Sixties their time would have seemed sedate if not actually quaint. Much as the Sixties do to us today. But what matters how those eras felt from the inside. Objects which to us seem quaintly retro then felt almost impossibly futuristic.

And this has an extra resonance for ’Star Trek’, itself futurist in the techno-utopian sense of linear progress. But is all that progress now happening too fast, too soon? Characters here “burn out”, die from being accelerated.

As it turns out, the answer’s a reassuring no. It’s all happily resolved, with time turned back to its standard speed and cameras set back to their right angles. ’Wink of an Eye’ raises these concerns only to dispel them. In the future we’ll teleport places rather than catch the bus. But people will remain recognisably human, have comprehensible motivations, and coffee will just contain coffee.

At other points the show just temporarily tries on the counter culture, like a wage slave donning a hippy wig for the weekend. In ’I, Mudd’ the crew stage a happening to freak out the robotised squares holding them captive, who are soon crying out “Illogical! Illogical!” and overheating. (Actually not so soon. In the opposite to the Scalosians the scene transcends it’s literal length to become interminable.)

While ’Miri’ presents the generation gap as an infection. (One of many times when a negative social force is manifested as a disease.) In an era where youth protest was often dismissed as a simple failure to grow up, this literally infantilises those draft dodgers. Their ideology is irrationality, tantrum as political statement. The sloganising of demonstrators is reduced to taunting playground chants – literally “nyah, nyah, nyah”. They call adults ‘Grups’, short for ‘grown-ups’, midway between a childlike mispronunciation and a protest term like ‘pig’. Naturally they take against the Enterprise crew as more Grups and (in a somewhat symbolic move) steal their communicators, shouting “blah! blah! blah!” at Kirk as he tries to reason with them.

Yet it turns out even alien planets have outside agitators, and the children are revealed to be led by an older boy – Jahn. His resemblance to Scorpio in in the later ‘Dirty Harry’ (both below) is presumably coincidental, suggests they’re aiming at similar types.

Kirk insists “children have an instinctive need for adults; they want to be told right and wrong." And the episode is built, even titled, around a child who comes round to just that. We’re explicitly told both that Miri is barely pubescent and that she has a crush on Kirk, which is… well, let’s move on.

The adults are found to have caused the disease, with a resulting generational war fought on both sides. Yet it’s the children who are the antagonists. The adult characters appear early, offering portentous warnings which they underline by promptly dropping dead – like the harbinger in horror films. Perhaps significantly, the planet’s not an Earth nor a colony, yet looking exactly like the Earth even down to the shape of it’s continents. There is something cake-and-eat-it about this, that it’s our world yet simultaneously not. Yet it does hint the adults share at least some of the blame, a hint which is enlarged on in other episodes.

The infamous space hippies of ‘The Way To Eden’ are remarkably like the Planet People in ‘Quatermass’ (1979). They pursue a paradise planet which is almost certainly mythical. They reject rationalism like it’s a poison, when confronted with inconvenient facts they simply disregard them. “We recognise no authority, save that within ourselves” they insist. (In words strangely close to Crass’ dictum “there is no authority but yourself”.) Though professing to be free sprits they’re the duped disciples of their monomaniacal leader Severin, a clear Timothy Leary stand-in.

They hijack the Enterprise to take them to their Eden. Severin carries a disease (yes, another one), which this risks spreading to the natives. While their flight route also risks violates a fragile peace with the Romulans. When they get there the planet looks idyllic, but every living thing is full of acid (the other kind) and going barefoot in the grass does not end well. Severin would have poisoned a planet already poisonous, and almost triggers a space war to do so. Which feels a little like over-egging it, like one of those ‘Road Runner’ endings where the Coyote not only fails to catch his prey but falls off a cliff, gets hit by a rock and then run over by a train.

And yet at the very same time it’s busily lampooning those daft hippies with their silly costumes and daft slang it’s conceding they might have a point. Their music, while like a copy of ‘Hair’ except even worse than the original, allows them to extra-diegetically critique events, like the Ooma Loompas drawing moral through song in ‘Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory’ (1971). When Spock explains to Kirk the origin of their much-chanted insult, "Herbert was a minor official, notorious for his rigid and limited patterns of thought," he replies "Well, I shall try to be less rigid in my thinking."

As Josh Marsfelder comments “the Hippies were very much middle class in a way the previous and contemporary countercultural movements really never were: The major nerve centres of the Hippie movement were big Southern Californian universities… Now, look at who comprises our Space Hippies in ‘The Way to Eden’: "Starfleet Academy dropouts, the son of an ambassador, a disgraced physician and several scientific specialists.”

The hippies weren’t the black militants who could so easily be written off by resorting to racist stereotypes. They were our children, white as white, the educated youth who should be set to become the next generation of managers. And the episode itself seems unsure whether Kirk has a bemused sympathy with their youthful idealism or just has his hands tied by their social connections, dialogue veering between one and the other.

If one thing defined the hippie counter-culture it was a rejection of social conformity. Why should you spend your life doing what was expected of you? Why not live it like it was yours? They jeer “Herbert” at rule-makers and rule-takers alike. But that’s too broad to be a philosophy. They could be presented as anti-war, anti-consumerist or even anti wage labour. But the thing they go for is anti-technology. Not the environmentalism often parodied as anti-technology but the full monty.

True, hippies were latter-day Romantics, to whom science and technology represented a confining mindset. (Think of Blake’s quote: “For man has closed himself up till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.”) And in a quite overtly techno-utopian series this being even quasi-sympathetic would seem the biggest digression of all.

(In fact, proving that every parody will find its literalisation if you wait long enough, the Primitivist ‘thinker’ John Zerzan has written: “What ’Star Trek’ has to convey about technology is probably its most insidious contribution to domination… Always at home in a sterile container in which they represent society, the crew could not be more cut off from the natural world. In fact, as the highest development in the mastery and manipulation of nature, ’Star Trek’ is really saying that nature no longer exists.”)

Scotty proves their chief critic, grumbling about the “barefooted what-do-you-call-‘ems.” Yet in a series ever-fond of personalised debates he never argues the point with the crewman most sympathetic to them. Which turns out, despite their supremely illogical behaviour, to be Spock. He comments “there are many who are uncomfortable with what we have created. It is almost a biological rebellion – a profound revulsion against the planned communities, the programming, the sterilized, artfully balanced atmospheres. They hunger for an Eden.”

So why should the biggest technophile of them all, a character ceaselessly likened to a walking computer, harbour such sympathies? This homes in on something. The hippies seemed to their elders to be rejecting not even what seemed worst in modern society but best. Having lived through the Depression and the deprivations of the war years, their parents revelled in the new-found and hard-won material abundance. Now their own children rejected it outright. The Ex’s ‘We’ve Got Everything We Never Wanted’ was a later punk song, but it captures this sentiment. It felt so at odds, yet coming from a source so close… was this so deranged it had to really be visionary?

But perhaps the real clue as to how this can be tied up, after the over-laboured ending, is the final exchange between Chekhov and the space hippy chick he’s had the inevitable crush on….

“Be incorrect, occasionally.”

“And you be correct.”

“Occasionally.”

We’ve got out of balance, see. Their yanking of the steering wheel might initially be disruptive and careering, but is necessary to keep us on the straight and narrow. Timothy Leary said “you’ve got to go out of your mind in order to use your head.” Luckily, here others are volunteering to do the out-of-mind part for us, so we can still use our heads only better aligned.

A similar expression of the same idea comes in (the really not very good at all) ‘Assignment Earth’ where Roberta says: “That’s why some of my generation are kind of crazy and rebels, you know. We wonder if we’re going to be alive when we’re thirty.”

And wondering if they’ll let you make it to that magic age, suddenly not trusting anyone over thirty doesn’t seem quite so crazy after all. Except rebel is precisely what she doesn’t. Her role is structured over the dilemma over which appropriate adult to obey. When Special Agent Gary Seven convinces her he’s CIA she immediately trusts him, despite their not being entirely down with the kids. When she susses he’s fibbing it turns out okay anyway, because he’s from an even higher authority.

- ’And the Children Shall Lead’

To Boldly Get Far Out

The voyages of the starship Enterprise began in 1966, the year John Savage has claimed youth culture exploded. And should anyone doubt it was a Sixties show in the way we think of them, and the hemlines alone weren’t convincing, show them the scene in ’Wink of an Eye’ where Kirk literally drinks the Kool-Aid.

Okay, officially it’s coffee. But the drink-me potion speeds him up to the point where he can see the aliens aboard the Enterprise, moving too fast to be visible to mere human perception. Who, most noticeably, don’t try to conquer him but convert him to their perspective.

Kirk’s view of slowed time is presented by Dutch angles, a visual conceit often employed to represent drugs or general derangement. And much of the episode’s appeal lies in seeing something once familiar rendered askew. (Beyond a brief intro, everything takes place on the familiar Enterprise sets.)

There’s a clear parallel between its time distortions and the contemporary fashion in psychedelic music for speeding up and slowing down sounds. Wikipedia cites as one of the main characteristic of the style as “Dechronicization” which “permits the drug user to move outside of conventional perceptions of time”, mimicking the effects of LSD (allegedly).

George Harrison said after first taking the stuff: “There was no way back after that. It showed you forwards and backwards and time stood still.” The aliens are even called the Scalosians, as if associated with musical scales. The episode itself becomes a little like dropping something in the coffee cup on the viewer’s armchair.

However unlike other adversaries (some of which we’ll move on to) the Scalosians themselves don’t represent the counter culture. In fact they’re a(nother) dying race who vampirically require humans. Accelerated time isn’t an enemy to be overcome so much as a setting for the story.

But then the Sixties themselves seemed an accelerated blur, something hard to take in at the time. (A point made by Darren in The M0vie Blog.) This wasn’t just the tempo of music or the rapid spread of the counter culture, though it included both those things. Rather than anything, it was everything. Art, politics, technology... the world seemed to be changing right under you.

Hindsight can have a flattening effect. The Futurists, the art movement operating before the First World War, boldly asserted in their manifesto “Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.” But by the Sixties their time would have seemed sedate if not actually quaint. Much as the Sixties do to us today. But what matters how those eras felt from the inside. Objects which to us seem quaintly retro then felt almost impossibly futuristic.

And this has an extra resonance for ’Star Trek’, itself futurist in the techno-utopian sense of linear progress. But is all that progress now happening too fast, too soon? Characters here “burn out”, die from being accelerated.

As it turns out, the answer’s a reassuring no. It’s all happily resolved, with time turned back to its standard speed and cameras set back to their right angles. ’Wink of an Eye’ raises these concerns only to dispel them. In the future we’ll teleport places rather than catch the bus. But people will remain recognisably human, have comprehensible motivations, and coffee will just contain coffee.

At other points the show just temporarily tries on the counter culture, like a wage slave donning a hippy wig for the weekend. In ’I, Mudd’ the crew stage a happening to freak out the robotised squares holding them captive, who are soon crying out “Illogical! Illogical!” and overheating. (Actually not so soon. In the opposite to the Scalosians the scene transcends it’s literal length to become interminable.)

While ’Miri’ presents the generation gap as an infection. (One of many times when a negative social force is manifested as a disease.) In an era where youth protest was often dismissed as a simple failure to grow up, this literally infantilises those draft dodgers. Their ideology is irrationality, tantrum as political statement. The sloganising of demonstrators is reduced to taunting playground chants – literally “nyah, nyah, nyah”. They call adults ‘Grups’, short for ‘grown-ups’, midway between a childlike mispronunciation and a protest term like ‘pig’. Naturally they take against the Enterprise crew as more Grups and (in a somewhat symbolic move) steal their communicators, shouting “blah! blah! blah!” at Kirk as he tries to reason with them.

Yet it turns out even alien planets have outside agitators, and the children are revealed to be led by an older boy – Jahn. His resemblance to Scorpio in in the later ‘Dirty Harry’ (both below) is presumably coincidental, suggests they’re aiming at similar types.

Kirk insists “children have an instinctive need for adults; they want to be told right and wrong." And the episode is built, even titled, around a child who comes round to just that. We’re explicitly told both that Miri is barely pubescent and that she has a crush on Kirk, which is… well, let’s move on.

The adults are found to have caused the disease, with a resulting generational war fought on both sides. Yet it’s the children who are the antagonists. The adult characters appear early, offering portentous warnings which they underline by promptly dropping dead – like the harbinger in horror films. Perhaps significantly, the planet’s not an Earth nor a colony, yet looking exactly like the Earth even down to the shape of it’s continents. There is something cake-and-eat-it about this, that it’s our world yet simultaneously not. Yet it does hint the adults share at least some of the blame, a hint which is enlarged on in other episodes.

The infamous space hippies of ‘The Way To Eden’ are remarkably like the Planet People in ‘Quatermass’ (1979). They pursue a paradise planet which is almost certainly mythical. They reject rationalism like it’s a poison, when confronted with inconvenient facts they simply disregard them. “We recognise no authority, save that within ourselves” they insist. (In words strangely close to Crass’ dictum “there is no authority but yourself”.) Though professing to be free sprits they’re the duped disciples of their monomaniacal leader Severin, a clear Timothy Leary stand-in.

They hijack the Enterprise to take them to their Eden. Severin carries a disease (yes, another one), which this risks spreading to the natives. While their flight route also risks violates a fragile peace with the Romulans. When they get there the planet looks idyllic, but every living thing is full of acid (the other kind) and going barefoot in the grass does not end well. Severin would have poisoned a planet already poisonous, and almost triggers a space war to do so. Which feels a little like over-egging it, like one of those ‘Road Runner’ endings where the Coyote not only fails to catch his prey but falls off a cliff, gets hit by a rock and then run over by a train.

And yet at the very same time it’s busily lampooning those daft hippies with their silly costumes and daft slang it’s conceding they might have a point. Their music, while like a copy of ‘Hair’ except even worse than the original, allows them to extra-diegetically critique events, like the Ooma Loompas drawing moral through song in ‘Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory’ (1971). When Spock explains to Kirk the origin of their much-chanted insult, "Herbert was a minor official, notorious for his rigid and limited patterns of thought," he replies "Well, I shall try to be less rigid in my thinking."

As Josh Marsfelder comments “the Hippies were very much middle class in a way the previous and contemporary countercultural movements really never were: The major nerve centres of the Hippie movement were big Southern Californian universities… Now, look at who comprises our Space Hippies in ‘The Way to Eden’: "Starfleet Academy dropouts, the son of an ambassador, a disgraced physician and several scientific specialists.”

The hippies weren’t the black militants who could so easily be written off by resorting to racist stereotypes. They were our children, white as white, the educated youth who should be set to become the next generation of managers. And the episode itself seems unsure whether Kirk has a bemused sympathy with their youthful idealism or just has his hands tied by their social connections, dialogue veering between one and the other.

If one thing defined the hippie counter-culture it was a rejection of social conformity. Why should you spend your life doing what was expected of you? Why not live it like it was yours? They jeer “Herbert” at rule-makers and rule-takers alike. But that’s too broad to be a philosophy. They could be presented as anti-war, anti-consumerist or even anti wage labour. But the thing they go for is anti-technology. Not the environmentalism often parodied as anti-technology but the full monty.

True, hippies were latter-day Romantics, to whom science and technology represented a confining mindset. (Think of Blake’s quote: “For man has closed himself up till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.”) And in a quite overtly techno-utopian series this being even quasi-sympathetic would seem the biggest digression of all.

(In fact, proving that every parody will find its literalisation if you wait long enough, the Primitivist ‘thinker’ John Zerzan has written: “What ’Star Trek’ has to convey about technology is probably its most insidious contribution to domination… Always at home in a sterile container in which they represent society, the crew could not be more cut off from the natural world. In fact, as the highest development in the mastery and manipulation of nature, ’Star Trek’ is really saying that nature no longer exists.”)

Scotty proves their chief critic, grumbling about the “barefooted what-do-you-call-‘ems.” Yet in a series ever-fond of personalised debates he never argues the point with the crewman most sympathetic to them. Which turns out, despite their supremely illogical behaviour, to be Spock. He comments “there are many who are uncomfortable with what we have created. It is almost a biological rebellion – a profound revulsion against the planned communities, the programming, the sterilized, artfully balanced atmospheres. They hunger for an Eden.”

So why should the biggest technophile of them all, a character ceaselessly likened to a walking computer, harbour such sympathies? This homes in on something. The hippies seemed to their elders to be rejecting not even what seemed worst in modern society but best. Having lived through the Depression and the deprivations of the war years, their parents revelled in the new-found and hard-won material abundance. Now their own children rejected it outright. The Ex’s ‘We’ve Got Everything We Never Wanted’ was a later punk song, but it captures this sentiment. It felt so at odds, yet coming from a source so close… was this so deranged it had to really be visionary?

But perhaps the real clue as to how this can be tied up, after the over-laboured ending, is the final exchange between Chekhov and the space hippy chick he’s had the inevitable crush on….

“Be incorrect, occasionally.”

“And you be correct.”

“Occasionally.”

We’ve got out of balance, see. Their yanking of the steering wheel might initially be disruptive and careering, but is necessary to keep us on the straight and narrow. Timothy Leary said “you’ve got to go out of your mind in order to use your head.” Luckily, here others are volunteering to do the out-of-mind part for us, so we can still use our heads only better aligned.

A similar expression of the same idea comes in (the really not very good at all) ‘Assignment Earth’ where Roberta says: “That’s why some of my generation are kind of crazy and rebels, you know. We wonder if we’re going to be alive when we’re thirty.”

And wondering if they’ll let you make it to that magic age, suddenly not trusting anyone over thirty doesn’t seem quite so crazy after all. Except rebel is precisely what she doesn’t. Her role is structured over the dilemma over which appropriate adult to obey. When Special Agent Gary Seven convinces her he’s CIA she immediately trusts him, despite their not being entirely down with the kids. When she susses he’s fibbing it turns out okay anyway, because he’s from an even higher authority.

If the kids are playing up, the cause is obviously poor parenting skills and there’s no need to listen to what they’re actually saying. (All of which is remarkably similar to the way Marvel comics of the era treated youth revolt.)

And yet as a child, when that line was first transmitted to me, I was gobsmacked. It had never been suggested before that the peace-freaks and deviants you saw on the news, who asked for trouble then complained when cops hit them, might have a point. Was this the much trumpeted ‘Star Trek’ liberalism, challenging the official orthodoxy? Or radical groups pushing their ideas into the mainstream, past the point where they could be simply suppressed? They only answer is yes. There’s no real way to assign proportions to each.

Coming soon! Racism. No wait, that’s already here. Racism in ‘Star Trek’…

And yet as a child, when that line was first transmitted to me, I was gobsmacked. It had never been suggested before that the peace-freaks and deviants you saw on the news, who asked for trouble then complained when cops hit them, might have a point. Was this the much trumpeted ‘Star Trek’ liberalism, challenging the official orthodoxy? Or radical groups pushing their ideas into the mainstream, past the point where they could be simply suppressed? They only answer is yes. There’s no real way to assign proportions to each.

Coming soon! Racism. No wait, that’s already here. Racism in ‘Star Trek’…

Saturday, 23 September 2023

“AS FAR AS WE CAN FLY”: ’SPACE RITUAL’ BY HAWKWIND

(Top 50 Albums)

“Originally we just wanted to freak people out but now we’re just interested in sound. For instance, if a monotonous sound like a chanting goes on long enough, it can really alter people's minds.… We try to create an environment where people can lose their inhibitions. We also want to keep clear of the music business as much as possible - just play for the people. It's like a ship that has to steer around rocks, we have to steer round the industry.”

- Dave Brock, ’NME’ (Jan ’71)

”Everything exists for itself, yet everything is part of something else.”

- ’Space Ritual’ sleevenote

“You couldn't overstate the importance of Hawkwind if you tried. They're a credible candidate for the most important band in the history of everything, ever.” - Me

”Waiting For Take-off”

”Space is one solution”

Finally, and perhaps the cherry to place on the top of all this, the first album containing no references to space. Though adverts for it still proclaimed “Hawkwind Is Space Rock”.

Now mention Hawkwind and most will say ‘Space Rock’ straight back at you. But then mention Space Rock and most will say ‘Hawkwind’. Pink Floyd’s early years notwithstanding, they pretty much define the genre. (As much as ex-member Lemmy’s next band, Motorhead, would do for Heavy Metal.) Partly because having had one… precisely one… hit single they fell into the strange situation of being the underground band the overground has heard of.

Okay, but Space Rock… was ‘space’ any more than just a euphemism for the verboten subject of drugs? Well partly, yes. ‘Acid rock’ often had the more mainstream-friendly (not to mention law-abiding) monicker substituted for it. And the lyrics to classic Hawkwind tracks such as ’Master of the Universe’ and ’Orgone Accumulator’ are respectively cosmological or Reichean, but those are fairly transparent metaphors for the real subject. (“It’s no social integrator/ It’s a one-man isolator”… hmm.)

Acid rock originally meant whatever soundtrack was added to Acid Trip parties. (Which early on was just regular rock music.) But Hawkwind weren’t just a setting to take drugs to, their music was a slightly different means to the same end. They nailed the notion of music as drug, music whose primary purpose was to alter the perceptions of the audience. Band members liked to tell the anecdote that they hid their drugs in their equipment, then kept prying police dogs away by playing sub lows at them. Which sounds a bit too good to actually be true. But there’s a symbolic kind of truth to it.

As Andrew Means said of them, “the listener is just as much a traveller as the musician”. Dave Brock cheerily conceded “it was basically freak-out music.”

And this is where space comes in, as a handy a metaphor for sonic exploration. It was a way of framing music which defied the confines of convention just like space transcends gravity. John Weinzierl of Amon Duul, more or less Hawkwind’s German cousins, summed up what it was to be radical youth at odds with all around you: “We had to come up with something new… Space is one solution.”

But space also stood for both the beyond and the imagination, the outer and inner realms, inasmuch as they’re different things. Robert Calvert commented “we can hypnotise the audience into exploring their own space. Space is the last unexplored terrain, it’s all that’s left, it’s where man’s future is.”

While Brock said: ”We were all reading science fiction and after the first moon landing, exploring the idea that everything could change. We were taking LSD, and the journey outward was also an inner journey, I suppose.” (Which was exactly what drew me to Science Fiction as a youth. And a huge part of the initial importance of Hawkwind to my young self was that you could get your music and your Science Fiction in one serving.)

Ken Kesey was ever-keen to point out that it was a CIA weapons programme which had given hippies LSD to take, initially literally. So it’s fitting that the other great product of the Cold War, the Space Race, provided the other escape route.

One route to sonic exploration was free jazz. Nik Turner described his aim as to “play free jazz in a rock band.” He’d hung out with free jazz players while travelling through Berlin, who were key in persuading him that expression was more important than technical ability. This was more to do with the approach than the sound. Though some of his sax playing can be very free jazz, particularly on ’You Shouldn’t Do That’.

But overall, their biggest free jazz inheritance was less direct. It was the way the band played in the moment and proved themselves so adept at improvisation. In the BBC documentary ’This Is Hawkwind, Do Not Panic’ Lemmy recalled: “It was a real rapport. We could be facing different ways and change at the same time during a jam… I’ve never had that since. I’ve never had it before that, come to that.”

This was the Sixties era, where collectivism held sway. (The line from ’Sonic Attack' “think only of yourself” is clearly intended as the Devil talking.) As Murray Ewing notes “how much the lyrics are about ‘we’ and ‘us’, ‘Deep in our minds’, ‘we shall be as one’, ‘So that we might learn to see/The foolishness that lives in us’. Consciously tribal, Hawkwind were seeking to create a communal experience.” Added to which vocals are often chanty and choral-sounding, even with a whiff of folk to them. (This was perhaps only true for Brock. But then Brock contributed so many of the vocals.)

Yet Turner’s squalling sax is on the same track as some of the most intense riffing you’re likely to hear. ’You Shouldn’t Do That’, a sixteen-minute epic, audaciously opened their second album ’X In Search Of Space’ (1971). Repetition and sensory overload should surely be contrary forces, yet here they’re combined into one heady brew. It may well be the band’s finest studio moment.

Joe Banks tried to capture their recipe:“Hawkwind took the heavier end of the 60s underground sound as a starting point and created a monolithic concoction of garage rock, primitive electronics and free jazz, with the power of repetition and the riff always to the fore.” And he’s right about the riffs. Hawkwind’s USP was to combine the earthiness of hard rock with the spaciness of… well, space without losing the benefits of either.

Pink Floyd, then still darlings of the UFO club rather than arena fillers, were an early influence. But, as so often, it’s the differences which are significant. On ’Interstellar Overdrive’, aesthetes and post-graduates, Floyd dispense with the riff almost as soon as they can. They just needed a countdown routine, a hand-hold to hook the listener, before dumping them deep in zero gravity. Whereas Hawkwind, deranged freaks, pile on the riff with the zeal of young lovers.

Banks again: “Hawkwind’s willingness to let the music splurge messily outside the lines - to overwhelm a song’s structure without destroying it - is what sets them apart from the rest of the British rock scene….In a scene dominated by music that values technical flash over visceral noise, Hawkwind are travelling in the opposite direction by unlearning the rules of traditional blues-based rock.”

Well, yes and no. There was a whole period where clueless music journos noted Hawkwind had synths and sang about space, and so labelled them Prog. (Partly because of the bozo assumption that anything early Seventies that didn’t look like Glam must by definition be Prog.) Despite them not having anything like the flamboyant approach to musicianship or the ‘clean’ sound of the genre. Rightly reacting against this, we tended to veer too far the other way and insist on their absolute originality.

Whereas, in truth, their genesis came amid an era of heavy riffing. ‘Hard rock’, a term which now sounds more like a tautology than something that needs inventing, came into common use around this time. Iron Butterfly’s ’In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’, released in 1968, had done much to trailblaze this. Hawkwind’s first album was released a mere two months after the Black Sabbath’s debut. (Who weren’t yet associated with a metalhead scene which was only starting to exist, but thought of as a “people’s band” much in the same way as Hawkwind. They may not have played as many counter-cultural benefits. But then who did?.)

”Perhaps The Dying Has Begun”

And this part-explains an often-asked question. In wider culture, they’re the British Grateful Dead, the symbol of a counter-culture which hadn’t died just because the media had announced it was time to move on. (Assisted by the way both bands has such vivid iconography, and such fanatical fans so given to networking.)

But the Grateful Dead had started in 1965, so it made some sense to see them as the emblem of an enduring Sixties. Hawkwind’s first gig wasn’t until 1969… until November 1969, barely scraping their way into the decade which supposedly defined them. And their first album didn’t appear until 1970, when the dream had been deemed over. Rob Chapman’s magnum opus ’Psychedelia and Other Colours’ (2015) mentions them not once. It seems a conundrum. How can you come so late to the party, and be its soundtrack? The answer to this is to turn the question the other way up.

It’s easy enough to portray hippies as blissed-out innocents, without a single salient idea beneath their headbands. Yet Hawkwind’s conception of space was one sometimes found in Science Fiction, where the Romantic notion of the Sublime was enhanced , extended and projected out onto the vastness of the cosmos. It’s where we must be, but at the same time it may well destroy us without even noticing. Think of the lyrics to ’Space Is Deep’:

“Space is dark, it is so endless

“When you're lost it's so relentless

“It is so big, it is so small

“Why does man try to act so tall?”

Or a couplet from ’Lord of Light’, which captures the perennial dualism: “A day shall come, we shall be as one/ Perhaps the dying has begun.” Or the way ’Brainstorm’ is simultaneously escape route from Earth, space rocket as one step up from teenage wheels (“Can’t get no peace till I get into motion/ Sign my release from this planet’s erosion”) and one-man suicide trip (“I’m breaking up, I’m falling apart/ I’m floating away.”).

True, psychedelic music hadn’t all been twee and pastoral. (However it was later caricatured.) Something like Pink Floyd’s ’Careful With That Axe Eugene’ was exquisitely sinister. But they were never so relentless, never so deranged, never bit into the brown acid as deeply as Hawkwind.

And where better to experience all of this than live? Live albums normally signify a band at an impasse. The label are on at them to put out something but they’re too coked up. Whereas Hawkwind were always primarily a live band. Their studio albums were often recorded in as close to live conditions as possible, sometimes containing live tracks regardless. But it was the all-live ’Space Ritual' where they really reached the stars. (Let’s see how many other entries in this top fifty are live albums. Not expecting a high number.)

And around this time they were gigging ceaselessly. Gigs organised like (in the album title) a ritual or (in the parlance of the time) a trip, rather than a live-action jukebox. And though culled from two separate shows, and requiring editing even to fit on a double LP, the album seeks to document that trip as much as possible. The three new tracks (‘Born To Go’, ‘Upside Down’ and ’Orgone Accumulator’) weren’t released on any subsequent studio album, confirming this was intended as a ‘proper’ release.

Brock… and it seems it mostly was Brock… had a gift for dynamics, both within and between tracks. He’d segue between the rocket-propelled heavy riffing tracks and the more lyrical numbers with finesse. For example from ’Born to Go’ into ’Down Through The Night’. These were often sung respectively by Turner and Brock, a similar dynamic to Waters and Gilmour in Pink Floyd from this era. (Most notably in ’Brain Damage’ where they trade vocals within one track.) And ’Space Ritual’ segues all the way through, not breaking for applause till the finale.

However, while it’s great we get to hear it, it’s shame we can’t see any of it. The band had ploughed the profits from their one hit single into creating an audio-visual experience. But filming, especially under stage lights, was a more expensive and technically challenging prospect in those far-flung days.

”World Turned Upside Down Now”

’Orgone Accumulator’ proved to be the pointer towards the next era of Hawkwind - not spacey but sleazy, low-down and rumbling. Rather than the riff just being the touch-paper to the sonic derangement, the track sticks unrelentingly with the riff like a pair of tight-fitting jeans, all rocket propulsion with no zero gravity. It’s described by Joe Banks (in the Quietus) as “brilliantly moronic”.

To quote Murray Ewing again: “A community-binding collective of tribal shamans no more, Hawkwind became something like a normal band.” In the clearest sign of a changing of the guard, Dik Mik was replaced by the classically trained Simon House. (Though Del Dettmar stayed for one more album.)

Tracks became more like songs. Lyrics, which had been concerned with evoking the sense of something, more took up scenarios or even mini-narratives. Sleeves went for a more regular fantasy look. See for example the next release, 1974’s ’Hall of the Mountain Grill’ below. (The front cover, if not the back, is still by Barney Bubbles. But it’s an SF image adorned by band logo and album title, unlike the integrated design of earlier.)

But if they were now less space more rock, this was still a pretty good seam of rock. If they were no longer astral travellers, they were finding some pretty good places to visit on the ground. Though naysayers portray Hawkwind as something stuck in the Sixties it would be truer to say the very opposite, that they acted as a barometer of change. Their late Seventies era was full of dystopian grandeur, befitting the sourer times. The classic line was from ’High Rise’ – “He was just like you might have been/ On the ninety-ninth floor of a suicide machine”. It’s all that communal “we” chanting inverted. Now we all succumb to the same fate. Just one at a time.

”We Turned All This Noise On”

The winged shadow of Hawkwind is cast far and wide. Like Black Sabbath they may have stamped their identity on a genre, but their influence went way beyond that. John Lydon (ostensibly the default anti-hippy) has recounted buying their first album, and played no less than ’You Shouldn’t Do That’ when given a BBC radio show, while the reformed Pistols covered ’Silver Machine’. Joe Strummer was a fan, as were Black Flag's Henry Rollins and Dez Cadena. Crass' original mission statement was to be to the Pistols what Hawkwind were to the Beatles.

…and we’re not done yet, that was just the punks! Conrad Schnitzler, founder member of Kluster and Tangerine Dream, called them his favourite band. When Joy Division turned into New Order and took up electronics, they emulated Hawkwind. The Orb recorded a tribute called Orbwind.

Nigel Ayers of Nocturnal Emissions saw Hawkwind as the primary influence on Industrial and Noise music: “This is something that they rarely mention in the press, as Hawkwind have this reputation as a British ‘hippie band’… Whereas if they were a German hippie band… Zoviet France have told me they were very keen on Hawkwind. SPK were well into Hawkwind back in Australia… Hawkwind were the first band I was aware of to popularise the idea of sonic attack - infra and ultra sound as a weapon… Whenever I saw Throbbing Gristle I thought ‘Hawkwind without the lights and without the tunes’.” (‘Sound Projector’ 7, 2000)

In fact Throbbing Gristle, then trading as COUM Transmissions, played their first gig supporting Hawkwind. Even after becoming TG, they traded under the description “post-psychedelic trash”, while Simon Reynolds describes their sound (quite accurately) as “psychedelia inverted”.

Want to experience the vastness of space? Don’t hand over your savings to Branson or Bezos. Just get hold of these three albums, and you’ll be out there in no time.

“The streets were our oyster,

“We smoked urban poison,

“And we turned all this noise on,

“We knew how to fight.

“We dropped out and tuned in,

“Spoke secret jargon,

“And we would not bargain,

“For what we had found,

“In the days of the underground”

- ‘Days Of The Underground’

Otherwise unattributed quotes are from Joe Banks’ ‘Hawkwind: Days Of the Underground’ (Strange Attractor Press), which is a labour of love - with all the advantages and disadvantages that brings.

“Originally we just wanted to freak people out but now we’re just interested in sound. For instance, if a monotonous sound like a chanting goes on long enough, it can really alter people's minds.… We try to create an environment where people can lose their inhibitions. We also want to keep clear of the music business as much as possible - just play for the people. It's like a ship that has to steer around rocks, we have to steer round the industry.”

- Dave Brock, ’NME’ (Jan ’71)

”Everything exists for itself, yet everything is part of something else.”

- ’Space Ritual’ sleevenote

“You couldn't overstate the importance of Hawkwind if you tried. They're a credible candidate for the most important band in the history of everything, ever.” - Me

”Waiting For Take-off”

’Space Ritual’ (known by pedants as ’The Space Ritual Alive In Liverpool and London', 1973) is the finale and cumulation of Hawkwind’s classic space trilogy - following from and building on ’In Search Of Space’ (1971) and ’Doremi Farso Latido’ (1972). Citation does not seem needed. So what led to such an outpouring of awesomeness as this?

We have something of a clue in an earlier release, their eponymous debut. Which stated in the liner notes “by now we will be past this album”, suggesting they regarded it as something of a staging post. (It was after all released in April 1970, by a band who had only played their first gig in November 1969.) And I’m going to suggest that it lacks four vital elements…

First, though Nik Turner plays on the debut, he sang no lead vocals. Now, Dave Brock was the founder and band leader. (And sole constant member, up til today.) Who sang, frequently. But the founder felt no inclination to be the front man. Turner, whose initial involvement had been as a roadie, fell into that role but once there took to it with some relish.

They were described by frequent collaborator Michael Moorcock as, respectively, the band’s backbone and spirit. Brock was the tent pole, keeping the band up. But Turner was the carney character who called the punters in. (Though he sometimes shared, sometimes alternated that role with Robert Calvert. No-one has ever said Hawkwind’s history is insufficiently confusing.)

Second, though Dik Mik contributed electronics for the first album he didn’t team up with Del Dettmar till the second. (Dettmar was credited for synths, Dik Mik for “audio generator”. I have no idea what that is.) Now this was a time when bands often turned to electronic music. But the new instruments were mostly played in the old way, as if a concert pianist had his Steinway swapped for a synth at the last minute. Whereas with Hawkwind…

The first ever electronic film soundtrack, by Louis and Bebe Barron for ’Forbidden Planet’ (1956), had been credited as “electronic tonalities” rather than music. (Largely to circumvent their non-membership of the Musician’s Union. But it’s still a good description.) And Dik Mik and Dettmar worked in a similar way. They’d surge unpredictably, their sound barely controllable, like even the player isn’t really sure what’s going to happen next. And as both were more tinkering boffins than proper musicians that’s not altogether surprising. They saw their role as to “add atmospherics”. And electronics from this early era often has this quality, as if the preserve of haphazardly gifted amateurs, the Doctor in the Tardis rather than Jean Luc Picard aboard the Enterprise. More the Silver Apples than Rick Wakeman.

But the main giveaway is that it lacks the brilliant ‘cosmic hieroglyph’ cover designs Barney Bubbles would provide for the space trilogy. These were complete and integrated works of design, rather than just a logo slapped atop an image of the band. See for example ’In Search of Space' below. (Just about visible is the way the gatefold had a jagged centre opening.)

We have something of a clue in an earlier release, their eponymous debut. Which stated in the liner notes “by now we will be past this album”, suggesting they regarded it as something of a staging post. (It was after all released in April 1970, by a band who had only played their first gig in November 1969.) And I’m going to suggest that it lacks four vital elements…

First, though Nik Turner plays on the debut, he sang no lead vocals. Now, Dave Brock was the founder and band leader. (And sole constant member, up til today.) Who sang, frequently. But the founder felt no inclination to be the front man. Turner, whose initial involvement had been as a roadie, fell into that role but once there took to it with some relish.

They were described by frequent collaborator Michael Moorcock as, respectively, the band’s backbone and spirit. Brock was the tent pole, keeping the band up. But Turner was the carney character who called the punters in. (Though he sometimes shared, sometimes alternated that role with Robert Calvert. No-one has ever said Hawkwind’s history is insufficiently confusing.)

Second, though Dik Mik contributed electronics for the first album he didn’t team up with Del Dettmar till the second. (Dettmar was credited for synths, Dik Mik for “audio generator”. I have no idea what that is.) Now this was a time when bands often turned to electronic music. But the new instruments were mostly played in the old way, as if a concert pianist had his Steinway swapped for a synth at the last minute. Whereas with Hawkwind…

The first ever electronic film soundtrack, by Louis and Bebe Barron for ’Forbidden Planet’ (1956), had been credited as “electronic tonalities” rather than music. (Largely to circumvent their non-membership of the Musician’s Union. But it’s still a good description.) And Dik Mik and Dettmar worked in a similar way. They’d surge unpredictably, their sound barely controllable, like even the player isn’t really sure what’s going to happen next. And as both were more tinkering boffins than proper musicians that’s not altogether surprising. They saw their role as to “add atmospherics”. And electronics from this early era often has this quality, as if the preserve of haphazardly gifted amateurs, the Doctor in the Tardis rather than Jean Luc Picard aboard the Enterprise. More the Silver Apples than Rick Wakeman.

But the main giveaway is that it lacks the brilliant ‘cosmic hieroglyph’ cover designs Barney Bubbles would provide for the space trilogy. These were complete and integrated works of design, rather than just a logo slapped atop an image of the band. See for example ’In Search of Space' below. (Just about visible is the way the gatefold had a jagged centre opening.)

”Space is one solution”

Finally, and perhaps the cherry to place on the top of all this, the first album containing no references to space. Though adverts for it still proclaimed “Hawkwind Is Space Rock”.

Now mention Hawkwind and most will say ‘Space Rock’ straight back at you. But then mention Space Rock and most will say ‘Hawkwind’. Pink Floyd’s early years notwithstanding, they pretty much define the genre. (As much as ex-member Lemmy’s next band, Motorhead, would do for Heavy Metal.) Partly because having had one… precisely one… hit single they fell into the strange situation of being the underground band the overground has heard of.

Okay, but Space Rock… was ‘space’ any more than just a euphemism for the verboten subject of drugs? Well partly, yes. ‘Acid rock’ often had the more mainstream-friendly (not to mention law-abiding) monicker substituted for it. And the lyrics to classic Hawkwind tracks such as ’Master of the Universe’ and ’Orgone Accumulator’ are respectively cosmological or Reichean, but those are fairly transparent metaphors for the real subject. (“It’s no social integrator/ It’s a one-man isolator”… hmm.)

Acid rock originally meant whatever soundtrack was added to Acid Trip parties. (Which early on was just regular rock music.) But Hawkwind weren’t just a setting to take drugs to, their music was a slightly different means to the same end. They nailed the notion of music as drug, music whose primary purpose was to alter the perceptions of the audience. Band members liked to tell the anecdote that they hid their drugs in their equipment, then kept prying police dogs away by playing sub lows at them. Which sounds a bit too good to actually be true. But there’s a symbolic kind of truth to it.

As Andrew Means said of them, “the listener is just as much a traveller as the musician”. Dave Brock cheerily conceded “it was basically freak-out music.”

And this is where space comes in, as a handy a metaphor for sonic exploration. It was a way of framing music which defied the confines of convention just like space transcends gravity. John Weinzierl of Amon Duul, more or less Hawkwind’s German cousins, summed up what it was to be radical youth at odds with all around you: “We had to come up with something new… Space is one solution.”

But space also stood for both the beyond and the imagination, the outer and inner realms, inasmuch as they’re different things. Robert Calvert commented “we can hypnotise the audience into exploring their own space. Space is the last unexplored terrain, it’s all that’s left, it’s where man’s future is.”

While Brock said: ”We were all reading science fiction and after the first moon landing, exploring the idea that everything could change. We were taking LSD, and the journey outward was also an inner journey, I suppose.” (Which was exactly what drew me to Science Fiction as a youth. And a huge part of the initial importance of Hawkwind to my young self was that you could get your music and your Science Fiction in one serving.)

Ken Kesey was ever-keen to point out that it was a CIA weapons programme which had given hippies LSD to take, initially literally. So it’s fitting that the other great product of the Cold War, the Space Race, provided the other escape route.

One route to sonic exploration was free jazz. Nik Turner described his aim as to “play free jazz in a rock band.” He’d hung out with free jazz players while travelling through Berlin, who were key in persuading him that expression was more important than technical ability. This was more to do with the approach than the sound. Though some of his sax playing can be very free jazz, particularly on ’You Shouldn’t Do That’.

But overall, their biggest free jazz inheritance was less direct. It was the way the band played in the moment and proved themselves so adept at improvisation. In the BBC documentary ’This Is Hawkwind, Do Not Panic’ Lemmy recalled: “It was a real rapport. We could be facing different ways and change at the same time during a jam… I’ve never had that since. I’ve never had it before that, come to that.”

This was the Sixties era, where collectivism held sway. (The line from ’Sonic Attack' “think only of yourself” is clearly intended as the Devil talking.) As Murray Ewing notes “how much the lyrics are about ‘we’ and ‘us’, ‘Deep in our minds’, ‘we shall be as one’, ‘So that we might learn to see/The foolishness that lives in us’. Consciously tribal, Hawkwind were seeking to create a communal experience.” Added to which vocals are often chanty and choral-sounding, even with a whiff of folk to them. (This was perhaps only true for Brock. But then Brock contributed so many of the vocals.)

Yet Turner’s squalling sax is on the same track as some of the most intense riffing you’re likely to hear. ’You Shouldn’t Do That’, a sixteen-minute epic, audaciously opened their second album ’X In Search Of Space’ (1971). Repetition and sensory overload should surely be contrary forces, yet here they’re combined into one heady brew. It may well be the band’s finest studio moment.

Joe Banks tried to capture their recipe:“Hawkwind took the heavier end of the 60s underground sound as a starting point and created a monolithic concoction of garage rock, primitive electronics and free jazz, with the power of repetition and the riff always to the fore.” And he’s right about the riffs. Hawkwind’s USP was to combine the earthiness of hard rock with the spaciness of… well, space without losing the benefits of either.

Pink Floyd, then still darlings of the UFO club rather than arena fillers, were an early influence. But, as so often, it’s the differences which are significant. On ’Interstellar Overdrive’, aesthetes and post-graduates, Floyd dispense with the riff almost as soon as they can. They just needed a countdown routine, a hand-hold to hook the listener, before dumping them deep in zero gravity. Whereas Hawkwind, deranged freaks, pile on the riff with the zeal of young lovers.

Banks again: “Hawkwind’s willingness to let the music splurge messily outside the lines - to overwhelm a song’s structure without destroying it - is what sets them apart from the rest of the British rock scene….In a scene dominated by music that values technical flash over visceral noise, Hawkwind are travelling in the opposite direction by unlearning the rules of traditional blues-based rock.”

Well, yes and no. There was a whole period where clueless music journos noted Hawkwind had synths and sang about space, and so labelled them Prog. (Partly because of the bozo assumption that anything early Seventies that didn’t look like Glam must by definition be Prog.) Despite them not having anything like the flamboyant approach to musicianship or the ‘clean’ sound of the genre. Rightly reacting against this, we tended to veer too far the other way and insist on their absolute originality.

Whereas, in truth, their genesis came amid an era of heavy riffing. ‘Hard rock’, a term which now sounds more like a tautology than something that needs inventing, came into common use around this time. Iron Butterfly’s ’In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’, released in 1968, had done much to trailblaze this. Hawkwind’s first album was released a mere two months after the Black Sabbath’s debut. (Who weren’t yet associated with a metalhead scene which was only starting to exist, but thought of as a “people’s band” much in the same way as Hawkwind. They may not have played as many counter-cultural benefits. But then who did?.)

”Perhaps The Dying Has Begun”

And this part-explains an often-asked question. In wider culture, they’re the British Grateful Dead, the symbol of a counter-culture which hadn’t died just because the media had announced it was time to move on. (Assisted by the way both bands has such vivid iconography, and such fanatical fans so given to networking.)

But the Grateful Dead had started in 1965, so it made some sense to see them as the emblem of an enduring Sixties. Hawkwind’s first gig wasn’t until 1969… until November 1969, barely scraping their way into the decade which supposedly defined them. And their first album didn’t appear until 1970, when the dream had been deemed over. Rob Chapman’s magnum opus ’Psychedelia and Other Colours’ (2015) mentions them not once. It seems a conundrum. How can you come so late to the party, and be its soundtrack? The answer to this is to turn the question the other way up.

It’s easy enough to portray hippies as blissed-out innocents, without a single salient idea beneath their headbands. Yet Hawkwind’s conception of space was one sometimes found in Science Fiction, where the Romantic notion of the Sublime was enhanced , extended and projected out onto the vastness of the cosmos. It’s where we must be, but at the same time it may well destroy us without even noticing. Think of the lyrics to ’Space Is Deep’:

“Space is dark, it is so endless

“When you're lost it's so relentless

“It is so big, it is so small

“Why does man try to act so tall?”

Or a couplet from ’Lord of Light’, which captures the perennial dualism: “A day shall come, we shall be as one/ Perhaps the dying has begun.” Or the way ’Brainstorm’ is simultaneously escape route from Earth, space rocket as one step up from teenage wheels (“Can’t get no peace till I get into motion/ Sign my release from this planet’s erosion”) and one-man suicide trip (“I’m breaking up, I’m falling apart/ I’m floating away.”).

True, psychedelic music hadn’t all been twee and pastoral. (However it was later caricatured.) Something like Pink Floyd’s ’Careful With That Axe Eugene’ was exquisitely sinister. But they were never so relentless, never so deranged, never bit into the brown acid as deeply as Hawkwind.

And where better to experience all of this than live? Live albums normally signify a band at an impasse. The label are on at them to put out something but they’re too coked up. Whereas Hawkwind were always primarily a live band. Their studio albums were often recorded in as close to live conditions as possible, sometimes containing live tracks regardless. But it was the all-live ’Space Ritual' where they really reached the stars. (Let’s see how many other entries in this top fifty are live albums. Not expecting a high number.)

And around this time they were gigging ceaselessly. Gigs organised like (in the album title) a ritual or (in the parlance of the time) a trip, rather than a live-action jukebox. And though culled from two separate shows, and requiring editing even to fit on a double LP, the album seeks to document that trip as much as possible. The three new tracks (‘Born To Go’, ‘Upside Down’ and ’Orgone Accumulator’) weren’t released on any subsequent studio album, confirming this was intended as a ‘proper’ release.

Brock… and it seems it mostly was Brock… had a gift for dynamics, both within and between tracks. He’d segue between the rocket-propelled heavy riffing tracks and the more lyrical numbers with finesse. For example from ’Born to Go’ into ’Down Through The Night’. These were often sung respectively by Turner and Brock, a similar dynamic to Waters and Gilmour in Pink Floyd from this era. (Most notably in ’Brain Damage’ where they trade vocals within one track.) And ’Space Ritual’ segues all the way through, not breaking for applause till the finale.

However, while it’s great we get to hear it, it’s shame we can’t see any of it. The band had ploughed the profits from their one hit single into creating an audio-visual experience. But filming, especially under stage lights, was a more expensive and technically challenging prospect in those far-flung days.

”World Turned Upside Down Now”

’Orgone Accumulator’ proved to be the pointer towards the next era of Hawkwind - not spacey but sleazy, low-down and rumbling. Rather than the riff just being the touch-paper to the sonic derangement, the track sticks unrelentingly with the riff like a pair of tight-fitting jeans, all rocket propulsion with no zero gravity. It’s described by Joe Banks (in the Quietus) as “brilliantly moronic”.

To quote Murray Ewing again: “A community-binding collective of tribal shamans no more, Hawkwind became something like a normal band.” In the clearest sign of a changing of the guard, Dik Mik was replaced by the classically trained Simon House. (Though Del Dettmar stayed for one more album.)

Tracks became more like songs. Lyrics, which had been concerned with evoking the sense of something, more took up scenarios or even mini-narratives. Sleeves went for a more regular fantasy look. See for example the next release, 1974’s ’Hall of the Mountain Grill’ below. (The front cover, if not the back, is still by Barney Bubbles. But it’s an SF image adorned by band logo and album title, unlike the integrated design of earlier.)

But if they were now less space more rock, this was still a pretty good seam of rock. If they were no longer astral travellers, they were finding some pretty good places to visit on the ground. Though naysayers portray Hawkwind as something stuck in the Sixties it would be truer to say the very opposite, that they acted as a barometer of change. Their late Seventies era was full of dystopian grandeur, befitting the sourer times. The classic line was from ’High Rise’ – “He was just like you might have been/ On the ninety-ninth floor of a suicide machine”. It’s all that communal “we” chanting inverted. Now we all succumb to the same fate. Just one at a time.

”We Turned All This Noise On”

The winged shadow of Hawkwind is cast far and wide. Like Black Sabbath they may have stamped their identity on a genre, but their influence went way beyond that. John Lydon (ostensibly the default anti-hippy) has recounted buying their first album, and played no less than ’You Shouldn’t Do That’ when given a BBC radio show, while the reformed Pistols covered ’Silver Machine’. Joe Strummer was a fan, as were Black Flag's Henry Rollins and Dez Cadena. Crass' original mission statement was to be to the Pistols what Hawkwind were to the Beatles.

…and we’re not done yet, that was just the punks! Conrad Schnitzler, founder member of Kluster and Tangerine Dream, called them his favourite band. When Joy Division turned into New Order and took up electronics, they emulated Hawkwind. The Orb recorded a tribute called Orbwind.

Nigel Ayers of Nocturnal Emissions saw Hawkwind as the primary influence on Industrial and Noise music: “This is something that they rarely mention in the press, as Hawkwind have this reputation as a British ‘hippie band’… Whereas if they were a German hippie band… Zoviet France have told me they were very keen on Hawkwind. SPK were well into Hawkwind back in Australia… Hawkwind were the first band I was aware of to popularise the idea of sonic attack - infra and ultra sound as a weapon… Whenever I saw Throbbing Gristle I thought ‘Hawkwind without the lights and without the tunes’.” (‘Sound Projector’ 7, 2000)

In fact Throbbing Gristle, then trading as COUM Transmissions, played their first gig supporting Hawkwind. Even after becoming TG, they traded under the description “post-psychedelic trash”, while Simon Reynolds describes their sound (quite accurately) as “psychedelia inverted”.

Want to experience the vastness of space? Don’t hand over your savings to Branson or Bezos. Just get hold of these three albums, and you’ll be out there in no time.

“The streets were our oyster,

“We smoked urban poison,

“And we turned all this noise on,

“We knew how to fight.

“We dropped out and tuned in,

“Spoke secret jargon,

“And we would not bargain,

“For what we had found,

“In the days of the underground”

- ‘Days Of The Underground’

Otherwise unattributed quotes are from Joe Banks’ ‘Hawkwind: Days Of the Underground’ (Strange Attractor Press), which is a labour of love - with all the advantages and disadvantages that brings.

Saturday, 17 December 2022

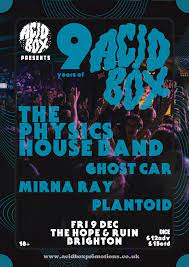

THE PHYSICS HOUSE BAND (GIG-GOING ADVENTURES)

The Hope and Ruin, Brighton

Fri 9th Dec

’Star Trek’, it seems, was wrong. You can change the laws of physics. It just takes you five years. At least that’s the length of time it’s been since I last saw the Physics House Band, and they do now sound quite different. In the intervening time, they’ve lost a bass player. There’s literallya space mid-stage where he stood. Which has changed their chemistry…. No, wait, that ruins the metaphor.

The guitarist now goes in for more power riffs. Which is actually a pretty smart solution to losing a bass player. The traditional rock-sound distinction is that the bass will play the beat and the guitar the melody, while a riff just lumbers in and does away with all that.

They’ve also replaced the bass with more saxophone. I’m not sure how that works, but it has. As the guitar rips into riffs the sax plays squalls above it. Which sounds counter-intuitive but works well. Think of a ballerina pirouetting around atop a Howitzer tank. Or something like that, anyway. When they do this it works very, very well. However…

They have often tended to peaks-and-valleys dynamics, something they npw do much more. And it was these sections which didn’t work for me. As the record shows I’ve been uneven in my response to this band. Which I suspect is more down to my subjective responses than their ability to do things right. And I found my response had become more uneven than it had been before.

A lot of music I like has no forward momentum, such as the minimalism of Reich or Glass. It can be fun to screw with time that way, to write numbers which effectively stop clocks. But if the music’s not moving, in any conventional sense, you have to like it where you are. And the view from these valleys simply didn’t do it for me.

Bands need to move on, and they’re not under any obligation to take you with them when they do. But I guess myself and the Physics House Band have now parted ways.

Fri 9th Dec

’Star Trek’, it seems, was wrong. You can change the laws of physics. It just takes you five years. At least that’s the length of time it’s been since I last saw the Physics House Band, and they do now sound quite different. In the intervening time, they’ve lost a bass player. There’s literallya space mid-stage where he stood. Which has changed their chemistry…. No, wait, that ruins the metaphor.

The guitarist now goes in for more power riffs. Which is actually a pretty smart solution to losing a bass player. The traditional rock-sound distinction is that the bass will play the beat and the guitar the melody, while a riff just lumbers in and does away with all that.

They’ve also replaced the bass with more saxophone. I’m not sure how that works, but it has. As the guitar rips into riffs the sax plays squalls above it. Which sounds counter-intuitive but works well. Think of a ballerina pirouetting around atop a Howitzer tank. Or something like that, anyway. When they do this it works very, very well. However…

They have often tended to peaks-and-valleys dynamics, something they npw do much more. And it was these sections which didn’t work for me. As the record shows I’ve been uneven in my response to this band. Which I suspect is more down to my subjective responses than their ability to do things right. And I found my response had become more uneven than it had been before.

A lot of music I like has no forward momentum, such as the minimalism of Reich or Glass. It can be fun to screw with time that way, to write numbers which effectively stop clocks. But if the music’s not moving, in any conventional sense, you have to like it where you are. And the view from these valleys simply didn’t do it for me.

Bands need to move on, and they’re not under any obligation to take you with them when they do. But I guess myself and the Physics House Band have now parted ways.

Saturday, 19 November 2022

OZRIC TENTACLES/ GONG (GIG-GOING ADVENTURES GO ALL COSMIC)

Concorde 2, Brighton, Thurs 18th Nov

Shortly after the sad death of Nik Turner seemed just the right time to attend an Old Hippies Reunited party, and as luck would have it a double-barrelled one came along…

I’m not sure how many time I’ve seen Ozric Tentacles now. There was a fifteen to twenty year period where it seemed almost impossible not to see them. Attend anything remotely resembling a festival or gathering and there they’d be. And I’m equally unsure when I last saw them, except it was some while ago. They would play regular venues too, but it what when that festival environment was clamped down on that they went out of my sight, like an animal losing its habitat.

Looking back, their sound was based on a kind of false memory. There wasn’t really a time when Psychedelic music overlapped with Prog, it was more than one waned as the other waxed. The bands who performed that transition, like Pink Floyd, tended to have a ‘mellow’ phase in-between. But that sound was why their best-known number came to be ’Kick Muck’, the guitar sounding less like a guitar and more like someone cranking furiously at a funnel which emits a ceaseless torrent of notes, so many and so fast they go by in a blur.

Guitarist Ed Wynne is the only survivor from back then. And the band’s become something of a family affair, featuring his ex-wife Brandi on bass, his son Silas Neptune on keyboards and a flautist and drummer whose names I failed to catch.

The standard thing to say about a longstanding band is what they’ve gained in ability they’ve lost in edge. Which sounds remarkably close to what music did when it morphed from Psychedelia to Prog. The greatest thing about Psychedelia being its abandon and derangement, and the worst thing about Prog being that it abandoned that abandon.

And for a band whose first-ever gig was a six-hour spontaneous jam at Stonehenge Free Festival in ’83, who often seemed to be jamming on stage, there seems little jam tonight. Wynne even introduced the tracks, something never done back in the day. The absence of ‘Jumping’ John Egan, who combined flute-plyaing with on-stage antics like a cosmic Bez, also changes the dynamic.

Nevertheless, if there’s now more smooth than rough, there was always some smooth. Unlike most festival circuit bands, they had (and have) the musical chops to work for those who stood to listen as well as those who waved their arms. There were points this set seemed to meander and my attention drifted, but overall it kept enough punch and was musically adventurous enough to take you with it.