When I was first getting into music, what histories there were faithfully followed a script. Rhythm & Blues’ role had been important but brief, to be the midwife of Rock & Roll. (And it normally was R&B, more than Gospel or Country.) It was portrayed as original but basic. It had taken black people to come up with it, all simple-minded yet pure of heart like they were. But it had taken white people to pick up on that and turn it into something.

Even R&B artists would at times go along with this, perhaps figuring it not best to bite the hand attached to the deepest pockets. None less than Muddy Waters sang ’The Blues Had A Baby And They Named It Rock and Roll’ (1977), which at least moved midwife along to mother.

But if anything, it was the other way up. Rock & Roll finally formally broke something which had in actuality been undermined in American music decades back, the colour bar. And that was a significant cultural event. But to do it, it had to dilute the material down for a mass audience, make it more palatable. (And the right term is mass, not white, audience. You could tell a similar story with Country.)

Big Joe Turner’s version of ’Shake, Rattle and Roll’ is not just better than Bill Haley’s, it’s better at all the things Rock & Roll is supposed to be good for. The same is true for Big Mama Thornton’s ’Hound Dog’ over Elvis’, and you could keep going.

But it’s more than that. The problem with constantly searching for the roots of Rock & Roll is that everything else just gets thrown away as a weed. When, if you just look at what’s in your hand, it can be the finest flower. We should stop seeing Blues as a staging-post to somewhere else, and start seeing it as a place in itself.

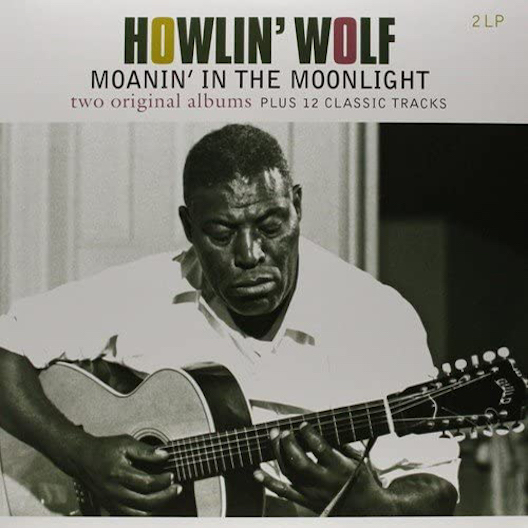

The two big stars of the classic post-war era of R&B were Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. Their creative rivalry was only accentuated by their being on the same label (Chess) and using the same main songwriter. (Willie Dixon, who would deliberately tell Wolf a song was already promised to Waters, knowing he’d then insist it had to be his.)

And they sound very little like someone trying to come up with Rock & Roll. True, there’s times they rock it, and as well as anyone. Wolf’s ’Rock It Boogie’ comes self-described. But, as a general rule, in straightening itself out in order to be made into Rock & Roll, Blues became a more rigid, more regularised form of music. In picking up the fixed-voltage power of electricity, it lost the free-form force of unpredictability.

Not so with our guys! Giles Oakley wrote “they can continue the use of country-style unpredictability in bar lengths, giving free range to the blues feeling surging through the whole band as if it were one man.” (‘The Devil’s Music’, 1976). He was talking of Waters’ band, but it applies to both. Rather than upbeat and animated, their music was measured and spacious, even laconic. (Perhaps best summed up by the Wolf lyric “Oh the church bell tollin’/ Oh the hearse come driving slow”. Not something you could sing over a Gene Vincent beat.) Harmonica was often then used to thread, bend and stretch between the placed-out guitar notes, like barbed wire curling round fenceposts.

And Waters was great. Truly great. But ultimately, Wolf was even better.

I’d first heard Blues early, as a child, as my Dad had some old records. And my young ears could barely take in music that sounded so unearthly, so totally removed from the Pop music and advertising jingles which I’d taken to be music.

He had no Howling Wolf. (Due, I’d suspect, to the lack of any ‘authentic’ acoustic era.) In fact I wasn’t to hear him until an adult. Whereupon, despite having had years to acclimate myself to music, when I finally got there he still sounded as unearthly as the Blues I’d first heard.

It is true that lyrically, particularly by the time of R&B, Blues did tend to prefigure Rock & Roll. And Wolf sang as much about the familiar themes as anyone else, women not being able to resist him, and his baby doing him wrong. (However those two were supposed to fit together.)

But his lyrics could also hinted at something sinister going on, at lurking, indeterminate menace. (Something people associate with Robert Johnston, but don’t imagine in electric Blues.) In the later track ’Ain’t Superstitious’ from 1961, the title phrase is continually countered by lots of good reasons to be superstitious. Yet, importantly, Wolf knew to never make it any more explicit than that. It was like that anxiety dream where you’re not sure quite what’s causing the anxiety, making you all the more anxious.

(And Blues was ever thus. All the things that books earnestly list as creating the genre, which basically come down to racism, are almost never referred to explictly in the music.)

And this perfectly matched his voice, gravelly but also given to unearthly, name-defining howls, wails and moans. (He liked to say he’d originally tried to yodel like Country star Jimmie Rodgers, but howls were simply what had come out of his throat and so he’d gone with them.) Suffice to say, if you take to Wolf’s voice, you’ll most likely take to everything else about him.

And voice and lyrics were then married to the spectral music, sounding like it could pass through walls. The opening track ’Moanin’ At Midnight’ (1951) sums this up well. It starts with Wolf literally setting the tone with a low moan, as if retuning you into his frequency. Surely one of the greatest track openings of all. It’s the equivalent of saying “who-hoo” in a ghost story, except in a way that actually works.

It’s a classic example of the combination effect in music, the whole being more than its parts. Lyrics like “Somebody calling me/ Calling on my telephone” scarcely sound like Pulitzer prize stuff. But add it to the voice and the music and the result is spine-tingling.

First, this was never planned as an album. The currency of R&B was the single, at most the EP. The Billboard R&B chart, which began in ’49, even included jukebox plays alongside record sales. This album, though put together back in the day, was complied from already released singles. (In ’59, from material dating back to ’51.) And that was what albums were to Chess, at least back them. (Fun fact! ‘Album’ originally referred to a clutch of 78s packaged together. It meant ‘separate things collected together’, like a stamp or photo album.)

And more broadly… the notion that Blues was, formally speaking, an authentic Folk art is nothing but a hopeless romanticism. It was a commercial genre, with labels as much hit factories as Motown would later be, which gave many a living and got some rich (Wolf included). However, it still retained many elements from folk culture. Including a lack of interest in originality. If someone had a new idea, whether a lyric or rhythm, that was simply taken as added to the buffet table. Everyone else just helped themselves, and were unabashed about doing it.

And if that person who had the new idea was you, then what else would you do but copy yourself? Stars would commonly cover their own songs under different aliases. Sometimes this was to slip through contractual obligation. But it was more than that, songs didn’t have some definitive ‘finished’ version, like novels or paintings. They were fluid things, changing with each iteration.

So the line between one song and another naturally became thin and porous. Recording essentially the same track with a few elements shifted around was par for the course. R&B was only interested in what worked. And Wolf himself did all three of these - borrowed from others, got borrowed from by others, and recycled his own best ideas.

So if the measure of R&B is its effect on R&R, Howlin’ Wolf’s was probably nil. But that’s because it took rock music over a decade to catch up with him. Sam Phillips claimed he was the greatest artist he ever worked with, despite going on to record the Sun Records roster. Dylan named him as the best live act he’d seen. The Stones, though named after a Waters song, called him “one of our greatest idols” and covered ’Little Red Rooster’. The Doors did ’Back Door Man’, while Marc Bolan stole ’You’ll Be Mine’ and Led Zeppelin ’Killing Floor’… the list goes on. And you hear his howl all the way through Tom Waits and Captain Beefheart. Hail the wolf!

No comments:

Post a Comment