(The latest in our look at Pariah Elites in fiction. Again with PLOT SPOILERS. First instalment here. Full list here.)

“Who are these children? There’s something about the way they look at one with those curious eyes. They are - strangers, you know.”

”In Arcadian Indistinction”

So John Wyndham wrote ‘The Chrysalids’, a commentary on the generation gap via the metaphor of psi powers. Which could be summed up a one-nil to youth. But, fifty-two when this was published and not necessarily down with the kids, he essentially played out the scenario again - and in reverse. ’The Midwich Cuckoos’ (1957) was to take on the perspective of the parents.

Should you not know the plot… everyone in the rustic village of Midwich is struck asleep at once. And when they awake, all the women have become pregnant. (Even the virgins, in what cannot feel other than a twist on immaculate conception.) And the children they carry turn out to be cuckoo-like aliens, sporting.. you may be ahead here… enhanced mental powers. If 'The Chrysalids’ could be reduced to the line “they cannot tolerate our rise”, this would be ‘Adults come from Earth, children from Venus.’

Brecht’s plays ‘He Who Says Yes’ and ‘He Who Says No’ (both 1930) rehearse twin arguments, whether a child should or should not be left behind for the greater good. But he rigs the odds each time, introducing different criteria which determine each of the courses of action, undermining any actual comparisons. And this is essentially what Wyndham does in these two books.

(I rather like the idea of two novels looking at the same events, one from one side’s perspective, the other from the norms. As if such divergent views couldn’t be contained within one cover. But that’s not at all what Wyndham has done.)

First and most obviously, we have the change in setting to ’The Chrysalids’ - back to more familiar territory in about every way. As we’ve looked at before on this blog, as one of the first countries to urbanise Britain developed a culture which venerated rural life. More than Big Ben or Saint Pauls, the Post Office and the bicycled bobby were our symbols. Wartime films such as ’Went The Day Well?’ (1942) showed rustic villages being taken over by foreign invaders not as some staging-post to London, but as if the heart of the nation was already seized.

And Wyndham does something similar with his more alien disturbing of Midwich’s restive calm. The first chapter reads like one of those spotters’ guides to English villages, pointing out the age of the apse in the local Church, so beloved to my parents. (He wrote much of the novel in the Hampshire village of Steep, as if gazing out the window for location information. The nearby, and similar-sounding, Midhurst has also been suggested as a source.)

Had none of the events in ’The Chrysalids’ happened, it would still have been a dystopia. Not just for the powered children, objectively a dystopia. Instead it’s their telepathy which offers a route out of the situation. Whereas, had none of the events in ’Midwich Cuckoos’ happened, had none of the Children arrived, English villagers would have led lives of, in Wyndham’s phrase, “Arcadian indistinction”.

Murray Ewing describes Wyndham’s writing style as “analgesic”. But its in Midwich where he goes into analgesic overdrive. The horror of the situation doesn’t rear up, it creeps up on you, slowly and remorselessly.

’Day of The Triffids’ had a weight of backstory to convey, but front loaded action before filling us in. This book devotes much time to explaining what happened in Midwich before the incident, which boil down to “nothing much”. Which may lay it on a little. The first six chapters, the first quarter of the book, tellingly have Midwich in their name. And only in the last of these do the mass pregnancies even happen. Though, inevitably, we now know what comes next and are in a hurry to get there. Wyndham’s intended reader didn’t, and so quite possibly wasn’t.

”In Arcadian Indistinction”

So John Wyndham wrote ‘The Chrysalids’, a commentary on the generation gap via the metaphor of psi powers. Which could be summed up a one-nil to youth. But, fifty-two when this was published and not necessarily down with the kids, he essentially played out the scenario again - and in reverse. ’The Midwich Cuckoos’ (1957) was to take on the perspective of the parents.

Should you not know the plot… everyone in the rustic village of Midwich is struck asleep at once. And when they awake, all the women have become pregnant. (Even the virgins, in what cannot feel other than a twist on immaculate conception.) And the children they carry turn out to be cuckoo-like aliens, sporting.. you may be ahead here… enhanced mental powers. If 'The Chrysalids’ could be reduced to the line “they cannot tolerate our rise”, this would be ‘Adults come from Earth, children from Venus.’

Brecht’s plays ‘He Who Says Yes’ and ‘He Who Says No’ (both 1930) rehearse twin arguments, whether a child should or should not be left behind for the greater good. But he rigs the odds each time, introducing different criteria which determine each of the courses of action, undermining any actual comparisons. And this is essentially what Wyndham does in these two books.

(I rather like the idea of two novels looking at the same events, one from one side’s perspective, the other from the norms. As if such divergent views couldn’t be contained within one cover. But that’s not at all what Wyndham has done.)

First and most obviously, we have the change in setting to ’The Chrysalids’ - back to more familiar territory in about every way. As we’ve looked at before on this blog, as one of the first countries to urbanise Britain developed a culture which venerated rural life. More than Big Ben or Saint Pauls, the Post Office and the bicycled bobby were our symbols. Wartime films such as ’Went The Day Well?’ (1942) showed rustic villages being taken over by foreign invaders not as some staging-post to London, but as if the heart of the nation was already seized.

And Wyndham does something similar with his more alien disturbing of Midwich’s restive calm. The first chapter reads like one of those spotters’ guides to English villages, pointing out the age of the apse in the local Church, so beloved to my parents. (He wrote much of the novel in the Hampshire village of Steep, as if gazing out the window for location information. The nearby, and similar-sounding, Midhurst has also been suggested as a source.)

Had none of the events in ’The Chrysalids’ happened, it would still have been a dystopia. Not just for the powered children, objectively a dystopia. Instead it’s their telepathy which offers a route out of the situation. Whereas, had none of the events in ’Midwich Cuckoos’ happened, had none of the Children arrived, English villagers would have led lives of, in Wyndham’s phrase, “Arcadian indistinction”.

Murray Ewing describes Wyndham’s writing style as “analgesic”. But its in Midwich where he goes into analgesic overdrive. The horror of the situation doesn’t rear up, it creeps up on you, slowly and remorselessly.

’Day of The Triffids’ had a weight of backstory to convey, but front loaded action before filling us in. This book devotes much time to explaining what happened in Midwich before the incident, which boil down to “nothing much”. Which may lay it on a little. The first six chapters, the first quarter of the book, tellingly have Midwich in their name. And only in the last of these do the mass pregnancies even happen. Though, inevitably, we now know what comes next and are in a hurry to get there. Wyndham’s intended reader didn’t, and so quite possibly wasn’t.

Further, ’Triffids’ stuck rigidly to its narrator’s perspective. For around half the book, he’s trying to find his love interest and we don’t know where she is because he doesn’t. ’Chrysalids’ isn’t so rigid because of the telepathy conceit, but has times when other characters fall out of contact with the narrator.

This book has a first-person narrator too. But there’s whole chapters he’s not present for, sections which go on so long you forget about him until he’s back. (There’s a brief ‘explanation’ he’s recounting events he was told of later.) At times, you’d be forgiven for thinking his presence was some sort of contractual obligation, which only required honouring formally.

Why the difference? If narrated by a Midwich local, this book has the village’s voice. Because this is not one person’s story, its the village’s story. With the assumption Midwich stands for the Home Counties, which stand for England, which stand for Britain. While we may react with derision to such a notion now, readers at the time would have taken this for granted. And its done because this is a story about our species encountering another. There needs to be a way this is conveyed collectively.

But things are taken further than that, and for their own reasons…

Mostly, one character relays events to some of the others, which they then discuss which something not far from philosophical detachment. Throughout, events occur at a distance - reported on, or sometimes elided over. Both ’Triffids’ and ’Chrysalids’ are rip-roaring action-adventures by comparison.

Advice is dispatched by Zellaby, some sort of public intellectual, the pipe-puffing equivalent of Dr. Vorless from ’Triffids’. (It’s surprising how many relate him to Coker, it’s definitely Vorless.) However, Vorless’ authority is effectively conveyed by his only appearing once, giving us our instructions and going. Whereas here its not the narrator but Zellaby’s perspective which dominates, which is of interested, detached contemplation But as we see him through the narrator this distances him further. We’re told: “as so often with Zellaby, the gap between theory and practical circumstances seemed too inadequately bridged.”

To use a term Graham Greene was fond of, this is a story of an involvement. The whole book can often feel like one of his many discourses, speculating and ruminating. At first he sees the changed Children purely as a fascinating object for study. But in the end… quite literally at the end he has to take himself out of his former existence, pontificating in studies before the dinner gong goes off, and get to grips with events. From thought to deed.

But Won’t Somebody Please Worry About the Children?

Zellaby is given to saying such things as “the desirability of intermittent periods of social rigidity for the purpose of curbing the subversive energies of a new generation.” Presumably to be brought about by the power of polysllabery alone. Or, at another point…

“The true fruit of this century has little interest in coming to living-terms with innovations; it just greedily grabs them all as they come along. Only when it encounters something really big does it become aware of a social problem at all, and then, rather than make concessions, it yammers for the impossibly easy way out, uninvention, suppression - as in the matter of The Bomb.”

(And we should note all of this gets settled by means of a bomb.)

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was formed the year this book was published. And Midwich’s, and therefore the novel’s, resident intellectual is here to tell us how foolish the demands of those ban-the-bombers are. Though to be clear, they aren’t being compared to the Children. Instead, they’re part of the problem the Children are able to exploit. Lives of post-war ease and comfort have left them ill-equipped for this struggle.

Why this desire to dunk on the new generation? One barometer of this would be the increase in higher education. Though the rise would curve up more steeply in the Sixties, the trend had already begun. And higher education offered youth something much closer to a space of their own than the parental home or workplace. The era where your children simply grew to replace you as you wore out, new parts to be slipped in the same mechanism, that was was coming to a close.

As an example, compare a still from the film (more of which anon) to another teacher-and-pupil image, from ’An Unearthly Child’, the first ever episode of ’Doctor Who’. About which I once said: “The focus is less on Susan than the fascination she exerts over her teachers… [they] stand behind, looking to her. But she gazes out of the frame as if it’s a world which doesn’t contain her… expression inscrutable.” (As also said at the time, her mystery is beguiling not threatening, a significant difference. But the similarity between the images is still striking.)

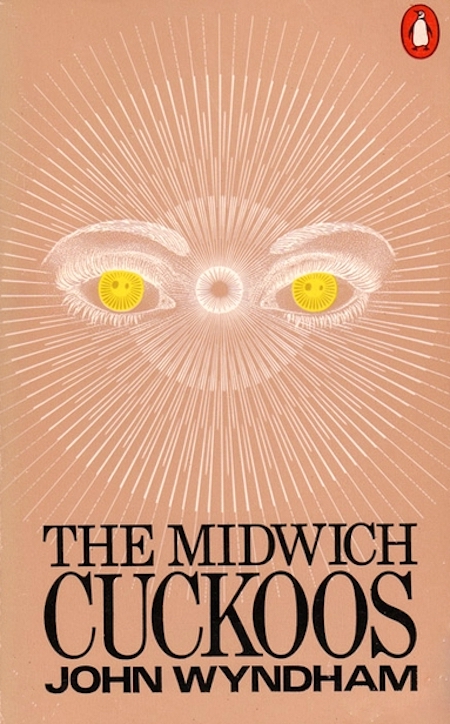

While one Penguin cover frames a single Child in the foreground, again looking away from his environment, in the all-black outfit stereotypical to Beatniks.

However, as with van Vogt’s slans, the Children develop faster than regular kids and so are of indeterminate age. In some, this leads to a tendency to take their oldest age and go into moral panics about the teenager, juvenile delinquency and so on. But this tendency shouldn’t be over-indulged. Much of the book is about the disturbing effect of them being simultaneously the Children and regular children.

Some themes are era-specific, others universal. And for something that’s universal, try this. You have a child. You created them from yourself, and yet they’re someone else. They arrive as a stranger to you. You cannot simply impose your will on them like they’re a remote limb of yours. Changeling stories unsurprisingly go back into folklore. (And get referenced here.)

Yet, as is often, this universal theme had an era-specific context. Dr. Spock’s manual ’Baby and Child Care’ had been influential on post-war attitudes. He asked parents to take their cues from children rather than impose a routine on them, ‘demand feeding’ becoming almost a byword for his school of thought. This was based on the idea that a child’s actions should be seen as natural and normal. And the inevitable phobia which came from this reassuring voice was an ‘otherly’ child, who was not and could not be explicable to you.

And yet who is missing from this perspective? Who is definitely not detached, and from the off?

“It’s all very well for a man. He doesn’t have to go through this sort of thing, and he knows he never will have to. How can he understand? He may mean as well as a saint, but he’s always on the outside. He can never know what it’s like, even in a normal way - so what sort of an idea can he have of this? - Of how it feels to like awake at night with the humiliating knowledge that one is simply being used? - As if one were not a person at all, but just a kind of mechanism, a sort of incubator…. And then to go on wondering… what, just what it may be that one is being forced to incubate. Of course you can’t understand how that feels - how could you? It’s degrading, it’s intolerable. I shall crack soon. I know I shall.”

Which seems so central to the main conceit that surely the whole thing would have been much more effective if our central character had been a woman. Yet of course here this is effectively a short-term plot obstacle, an attack of the vapours by Zellaby’s wife, to be overcome by reassuring male voices. And - par for the course - even this isn’t actually said by a woman, it’s Zellaby reporting his wife’s words.

The narrator has a wife too, but she is un-induced due to a plot device. While the child of Zellaby’s wife, despite the outburst above, turns out to be normal. His daughter does have a changed child, but he succeeds in sending her away from Midwich and thereby out of the novel. In short Wyndham seems to signpost this road, then baulk at the prospect and instead detour around it. So if analysts don’t seem to talk about this theme much, its submerged in the book itself.

”The Eyes That Shine"

The book was the first work of Wyndham’s to be filmed, in 1960. A film about as successful as the later adaptation of ’Triffids' was a failure. But that success may have led to it over-imprinting itself on the book in our minds. One edition used a film still on the cover, not something ever done with ’Triffids’. (And yes, it’s the image we looked at earlier.)

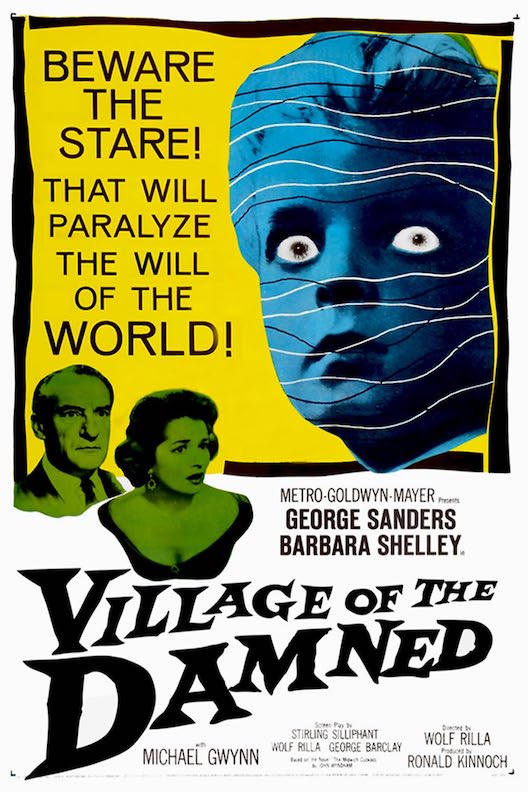

In general the differences are effectively conveyed by the change in title, to ’Village of the Damned’. The film’s much more dramatic and suspenseful, a streamlining of the sometimes languid novel. And if that sounds like a good thing, it probably is. It demonstrates how much of the book can be cut without losing anything essential, how much the analgesia was over-applied. The problem is, the film’s success is largely on its own terms.

Google Image ‘Village of the Damned 1960’ (to cut out the later version) and what dominates is those malevolent glowing eyes, lighting up whenever the Children use their sinister powers. The trailer opened with them and they were spelt out on the film poster. (“Beware the stare that will paralyse the will of the world!”)

In the book, in a not unusual motif, their strangeness also lies in their eyes. Yet in a characteristically quieter way, their eyes don’t light up but their irises are gold. (There are perhaps two phrases from the book which the film built on - “they had a quality of glowing gold” and “The… boy turned, and looked at us. His golden eyes were hard, and bright.”) Yet this film invention is present on almost all the later book covers. Only the 2000 Penguin edition keeps to the gold original.

Further, in the book they look alike. Not similar, not even like identical twins, more like clones, unrecognisable even by their birth mothers. There’s way more of them than in the film, in fact there’s fifty-eight. It becomes evident they share one mind. (“It will not be an individual who answers me, or performs what I ask, it will be an item of the group.”)

They mostly wander Midwich in an undifferentiated mass, neither spoken to by nor speaking to anyone. Direct, sustained conversation with them doesn’t happen until more than two-thirds in. (And they influence us with a thought. Why would they bother to talk to us much?) And when they do speak they neither try to conceal their nature, not exult in their success. (“He spoke simply, and without innuendo, as one stating a fact.”)

The film may well improve things by upping the stakes in giving Zellaby a changed son of his own. Amusingly called David, the same as the lead in ’The Chrysalids’. (Though most likely only by coincidence.) Yet this takes away even as it gives, assigning the Children a natural leader and spokesman, undercutting their collective otherness.

And if the dominant image of the film is the shiny eyes, the best-known scene is the final showdown - with the “I-must-think-of-a-brick-wall” business. Zellaby first wishes to break through the wall surrounding their minds and ends up building one to defend his own, his character arc in microcosm. (Its the briefcase, badge of his academic authority, that conceals the bomb.)

But this is played entirely differently in the book. There, as the narrator phrases it, the Children become children again, trustingly carrying in what they believe is part of his film projector equipment. It becomes almost a variant of the “could you kill baby Hitler?” quandary.

A dog reacts against baby David, as animals would in the later and more clear-cut horror ’The Omen’ (1976). Some versions of the film poster called them “Child-demons”. We’re explicitly told, in a actual dialogue quote, “these children are bad.” While Wyndham said, in a 1960 BBC interview, “they aren’t so evil in the original story”.

In the film the children are invaders, if with a slightly different strategy to the usual march across Westminster Bridge. But in the book they have less a strategy than an assumption - their superiority and therefore their success are taken as self-evident, they just need to await victory. And in this way the parallels actually function, they are like ’The Chrysalids’, in particular the Sealand woman who said “we cannot tolerate their obstruction”. As they say…

“This is not a civilised matter, it is a primitive matter. If we exist, we shall dominate you — that is clear and inevitable. Will you agree to be superseded, and start on the way to extinction without a struggle?”

While Zellaby comes to understand…

“We, like the other lords of creation before us, will one day be replaced. There are two ways in which it can happen: either through ourselves, by our self-destruction, or by the incursion of some species which we lack the equipment to subdue. Well, here we are now.”

The triffids may gesture towards weird fiction. Their way of being is wholly incomprehensible to us, even as they’re garden plants come to get us. While the Children, however strange and however powerful, have more explicable motivations. While still infants they punish their parents for accidentally harming them, ascribing motive to happenstance as children will. (One mother accidentally jabs her child with a safety pin while changing him, and he causes her to repeatedly jab her own arm.)

Even when older, they tolerate us insofar as we don’t get in their way. They stretch our terms of reference, but they don’t lie wholly outside of them. And this is necessary for the theme of evolution to apply. The Children come next after us.

Evolution was Wyndham’s theme, running (as we’ve seen) through all three of his main books. And there’s an odd paradox at the heart of this, for this “primitive matter” is simultaneously about who is the most evolved. In one sense, cosy Midwich is too evolved to deal with the problem of the Children, in that it’s too removed from the harsh imperatives of life. With nothing to threaten us, we’ve grown languid. The Children arrive to reassert the law of the jungle. (And Midwich’s civility is specifically posed as the problem. Children colonies are set up elsewhere but, foreign being a less well-behaved place, they’re soon wiped out.)

And yet at the same time the Children are more evolved. Evolution is an advance, and they look down at us norms from the next step up the ladder. And yet (again), at the immediate level evolution presents itself as a kind of trial by combat, victors surviving from one day to the next. Evolution is simultaneously a gladiatorial contest, decided in the cut-and-thrust of the arena, and a foregone conclusion.

Notably, both notions are widely considered part of evolution. Yet they’re pretty close to mutually exclusive. What’s more, if the first is true then the Children’s rise is inevitable. It would be like asking about the outcome of a knife fight where one brings a sharpened stone and the other a long-range missile. (And note Zellaby’s arc is not despair at the impossibility of resisting such a powerful foe, it’s about accepting his involvement in the battle of survival.)

Yet if Wyndham was aware of this paradox, there’s no sign of it in the book. His theme is the effect of evolution on popular culture. Yet by definition that means the effect of popular notions of evolution. The fears and dreams it led to didn’t come from it, at least not directly, they were fears and dreams we conjured up ourselves then assigned to it.

And speaking of winners and loser of evolution… well more of that in our final instalment…

No comments:

Post a Comment