From Daylight To Twilight (How Munch Became Munch)

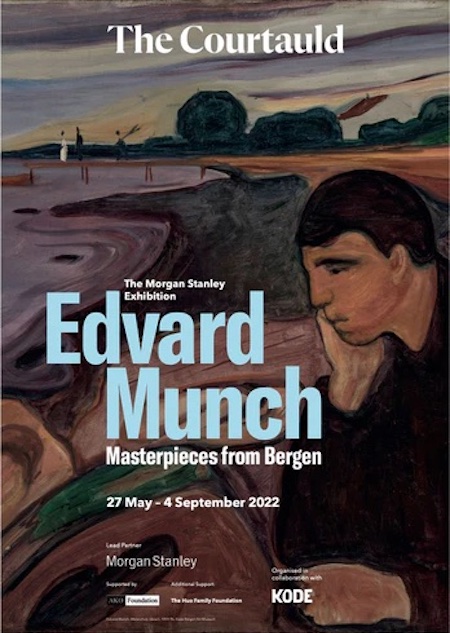

The Munch paintings in this smallish two-room show more normally reside in a dedicated museum in Bergen, in fact they haven’t been seen outside of Norway before. Perhaps unusually, they come from all stages of Munch’s career. Let’s start at the start…

The prime example of Expressionism, we soon discobver, started out as an Impressionist. That may be like discovering a Punk musician originally played Blues. It may be the more surprising thing that those early works hold up so well. To get here you need to walk through the Courtauld’s impressive Impressionist collection, Monet, Manets and Degas on all sides. Yet they don’t particularly pale in this fine company.

Take ’Morning’ (1884, above) with its captured moment in time, casual pose of the figure, precise play of light and the floorboards and side of bed seeming to extend out past you. It’s immediate, involving, like the painting’s not here but we’re there. It was a good enough stab at the style to flummox the Norwegian critics, who soon dubbed him ‘Bizarro’.

Or take ’Inger in Sunshine’ (1888, above), which manages to convey the sunshine despite being painted in Norway, and with what the show calls “shimmering colours”. Only the model’s impassive expression seems a departure.

But then try ’Summer Night: Inger On the Beach’ (above). It’s from 1889, only a year later. It takes the same model (one of his sisters), in a fairly similar outfit. But everything is now different, and Munch as we know him has arrived. She doesn’t look out but off, as if in a reverie.

The colours are flatter and more sombre. But two things stand out most of all. The lack of horizon line, the water extending past the edge of the frame. And that white dress makeing her the focus of the image, even though she’s not centred.

She isn’t placed before a setting, it’s built around her. This isn’t a slice of life but a psychodrama, a moodscape. Shoreline setting and twilight combine to create a liminal space, aids to help us guess what her pensive thoughts might be. As I said over the British Museum show of his prints: “Munch is perhaps the default example of an Expressionist artist, who painted not what he saw but what he felt.” In fact, the show is keen to say that it’s with this exact work that the shift occurred.

And he didn’t stop there. ’House in Moonlight’ (1893/5, above) is almost a series of theatre flats, where we work out what’s in front of what by placement, not perspective, the gate behind the woman, the house behind the gate and so on. (Only the very foreground, with the falling shadow, breaks from this.) And the greens look too green, the browns too brown, to be naturalistic. Everything we see here looks like a symbol.

Trapped In A Timeline

And ‘Woman in Three Stages’ (1894,) from the series ’The Frieze Of Life’ merely uses pictorial space as a backdrop to a light-to-dark timeline. Let’s get the obvious said first. The three stages of women, already referred to like points on a production line, are not-yet-ready-for-sex, ready-and-up-for-it and then past-her-sell-by. Just as with nature, Munch’s only interest in women seems to be what they can offer him. It shouldn’t be contentious to say this.

But let’s look more at how the theme recurs in other works on show here. At first glance, ’At the Deathbed’ (1985, above) more resembles the better-known ‘The Sick Child’ (1885/6). Both are inspired (if that’s the word) by the early death of his sister Sophie. Both split the frame, placing the sickly child on the left, the grieving adults on the right.

Yet in this work he inverts the figure and places her prone under a white sheet, as if already in her coffin. Which makes for a strong contrast to the assembled family, a cluster of black which extends beyond their mourning clothes to take up almost all the right section.

So we are almost back to the light-to-dark timeline of ’Woman In Three Stages’, merely with the middle figure removed. Sophie was fifteen when she died, but truncation makes this figure seem smaller. It’s as if she died before gaining the full awareness of death the adult figures are lumbered with, innocence your only possible protection against this world. It’s like the classic Larkin line amended: “Get out as early as you can, before the possibility of having any kids yourself has even arisen.”

’Four Stages of Life’ (1902, above), as the title suggests adds a stage. Though probably more significant is his arranging of the figures behind one another. The young girl isn’t just pushed to the front and given a red hat (with echoing flecks of red in her coat), she looks out at us, and so becomes our focus. She may even be pleased to see us.

While the figures receding along a receding road look progressively gloomier, and meet our gaze to lesser and lesser degrees, the third already seeming to wear a mask. With life reduced to a timeline, we can only focus our attention on the short-lived part that’s liveable.

’Evening on Karl Johan’ (1892, above) resembles the print ’Angst’ (1896) from the British Museum show, and indeed Munch had fixations he’d repeatedly hammer on. But there’s an irony here that the deep perspective and pushing of figures to the foreground, almost out of the frame, is an Impressionist device that almost takes us back to the start.

Except with them it would convey the vim and bustle of street life. While he uses it to get us eyeballed by that dead-eyed clump of black, with their identically blank expressions. This is like the mourning family from ’At The Deathbed’ transplanted. Last time I used an Eliot phrase to describe the pallor of those ghoulish faces, “the skull beneath the skin”. Let’s add another one, “I had not thought death had undone so many.”

As we saw in the British Museum show, Munch was very much a Bohemian who associated with other Bohemians and (at least at times) exulted in shocking polite society. Yet as we also saw, rather than any of the libertinism and hedonism we associate with Bohemianism, he gives us very much the reverse.

His family background was Pietist, an uber-Protestant group who saw little good in this world other than a way out of it, via connection to God. And he doesn’t upend or challenge any of that. He simply cuts the connection, leaving us marooned and bereft. Chesterton famously said “When a man stops believing in God he doesn't then believe in nothing, he believes anything.” Munch proves this wrong. He very much believed in nothing.

Right at the end are a few works by later Munch where, taking on a more optimistic perspective, he sought to portray human vitality. Which seems the opposite to what you tend to expect, that people start out full of vigour and drive to change the world, and as they age feel mortality slowly closing around them.

But it must be said these works are simply less involving to look at. Whether this is because he was faking the look, like giving a wan smile, because he was built to glower in the gloom, or simply because optimism is a harder look to pull off than pessimism… there’s probably no way of knowing. Whichever it is, Munch’s home ground was the liminal spaces.

No comments:

Post a Comment