“We do not want pretty pictures to be hung on drawing-room walls. We want to create… an art that gives something to humanity. An art that arrests and engages. An art of one’s innermost heart.”

- Edvard Munch

The Skull Beneath The Skin

So, Munch’s prints… in one of those things you won’t know till you’re told, he didn’t start making them until ten years into his career. But they came to cement his reputation. There were practical reasons for this, they were more easily acquired than paintings and better evaded censorship.

But also, we tend to parse paintings diegetically - as if they’re a window onto an actual space. Prints we accept more readily as artifice, as works of design. That’s why they can incorporate text or other seemingly extraneous elements. And Munch is perhaps the default example of an Expressionist artist, who painted not what he saw but what he felt. He often gave works thematic titles such as ’Despair’, ‘Jealousy’ and ’Angst’. Prints simply worked for him.

For example, in ‘Self-Portrait With a Skeleton Arm’ (1895, above) his signature is on a white strip at the top of the frame. This feature is then echoed by the skeleton arm at the base. And we could probably argue for some time whether the arm’s another framing device or should be seen as attached to his shoulder. All of which directs our attention to something right at the edge of the frame.

Which is a skeleton arm. Art Nouveau, then a contemporary movement, was always decorating borders with fronds, inter-twined vines and other fecund growths. Munch brings in bones, a forerunner of Eliot’s famous phrase “the skull beneath the skin”.

Emily Spicer, at Culture Whisper, wrote “Munch was the art world’s answer to playwright Henrik Ibsen. He painted what the Norwegian writer penned for the theatre – jealousy, adultery, madness and disease.” The suggestion they’re in some way interchangeable takes it too far. Ibsen was much more the social commentator, and Munch the confessor of his own heart. But there was definitely an association. Munch designed theatre posters and screens for Ibsen, and painted his portrait.

And given its artifice the association of his art with theatre is strong. The contradiction of putting domestic life on stage, as actually experienced by the audience, runs through both. His compositions often look more like set designs than real places, for example ‘Death in the Sick Room’ (1896, below).

However this is an artifice we shouldn’t associate with fakeness or aestheticism, but quite the opposite. Do you want to become distracted by some detail of perspective or foreshortening, when your aim is to capture an emotional truth?

And it leads to what can feel like the bizarrest perspective on life for works created during the modern era. Munch could be called a Symbolist as much as an Expressionist, and his art’s an ominous realm stuffed with signs, portents and encounters with quasi-human figures - almost a retreat to Medievalism. And yet this matched his world all too well. It’s a combination also to be found in Strindberg (if less so Ibsen). In fact scientific advances seemed to feed this mysticism. Laura Cumming in the Guardian commented: “X-rays, ‘aura’ photographs, Freudian analysis: this was an age of strange revelations.”

Nature is a Language And It Screams

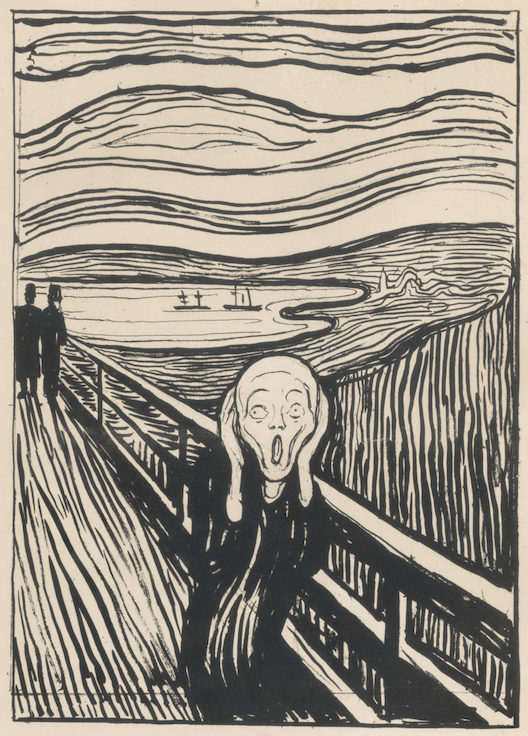

Though Munch made four versions of ‘The Scream’, his best-known work, that transfixed figure doesn’t travel much. The Tate exhibition of 2012 had to get by without one, and we’re excitedly told this is the first version to be shown in the UK for a decade. So unsurprisingly, the 1895 print (above) takes pride of place on the poster image.

If its Munch’s representative image, at least it’s typical. Though we’re given highly evocative slideshows of both Berlin and Paris, and hear him enthusing about life in both, his art remains set in this liminal Norway of bridges, shorelines and forests. His works sometimes seem to have been set within a radius of a few square miles.

The famous fact about ‘The Scream’ is that, even though his mouth is open, it’s not the figure doing the screaming. Look more to his hands, held over his ears. It’s virtually spelt out in words by the opening of Herzog’s 1974 film ‘The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser’: “Do you not then hear this horrible scream all around you that people usually call silence?”

Munch himself said “I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream.” And his own title for the work was ’The Scream of Nature’. We see the scream ripple through reality as if we’re looking at a seismograph, with the figure hopelessly trying to shut it out even as it bends like a reed in the wind.

Munch had been brought up by a pious, Pietist father. And Protestantism places a great emphasis on the word of God. We live in a vale of tears, a base place where all eventually die. Yet we hear the word of God, from outside of this, and feel redeemed. Hence the huge emphasis on prayer - eyes closed, ears open. While since Romanticism art had posited nature as the means by which we could re-find ourselves. Just to see it was considered rejuvenating. Consciously or otherwise, Munch brings us the worst of both worlds - here it’s nature which reduces to a sound, and it’s a scream.

However, there’s no getting around this – created to be reproduced, it became a victim of its success, too familiarised to remain potent. Inevitably there’s T-shirts, napkins, chocolates, ties and i-phone cases of it in the exit-through-gift-shop. Inevitably it even became an emoji. Even talking about how ubiquitous it has become seems of itself ubiquitous. But worse, much of what makes it ubiquitous also makes it insidious. In many ways, it encapsulates all that’s wrong about art from Modernism down to today.

Note the distinction of the main figure from the insensitive, tone-deaf others. Munch was accompanied by two friends the night of his dark revelation, who (unsurprisingly) heard nothing themselves. But that alone doesn’t explain why in all versions those two figures have to remain in, while pushed to the edge of, the frame. (And are then echoed by the two ships.)

Both Munch and Herzog discover the bohemian artist needs the conventional bourgeois to be defined against. His fine-tuned sensitivities have to be contrasted against the brute incomprehension exhibited by the rest of us. This trope of the suffering artist is of course absurd and tiresome, and gets rightly pilloried by AL Kennedy here. But we’ve still not arrived at the worst of it.

More pernicious still is that it turns the purpose of art upside-down. Note how, in the quote up top, Munch speaks of his “innermost heart”. The artist doesn’t articulate things which we might feel but be less skilled at expressing. Instead the artist parades his unique, rarified angst like a private horde of rubies, at which we less sensitive types can only gape in awe. The others could not hear the scream. The artist cannot not hear.

Munch was subject to both physical and psychological illness (once spending eight months in an asylum), which he seems to have parcelled together and fetishised. He commented “I would not cast off my illness, because there’s much in my art that I owe to it.”

So far so bad. Yet that’s not the whole of it. In an early version, the charcoal drawing Despair’ (1892, above) a full third is taken up by an explanatory text, suggesting the effect’s not being fully conveyed visually just yet. Once hit on, the modified pose seems obvious. But let’s concentrate here on the changed look of the figure.

Here he’s not recognisably Munch, but is obviously a Western man. In the final, famous version it’s simultaneously foregrounded and made more ambiguous. Often likened to an embryo, putative and genderless, in its way it’s like a stem cell out of which can grow any angst you’d like to profess. Which is the art that “gives something to humanity” in the quote up top.

It’s a paradoxical image. Munch universalises the figure at the very same time he reduces it to the suffering artist. Small wonder it’s so ubiquitous. It can stretch in two seemingly contradictory directions, which Munch himself seems to have regarded as interchangeable.

The Sickness At the Heart of Things

Munch saw the painting ‘The Sick Child’ (1907) as his breakthrough work, and in truth it probably is better than ‘The Scream’. The painting has an immediacy quite unlike the foreboding Symbolism of elsewhere, as if we’re actually in the room witnessing events. There’s just enough incidental detail, such as the edge of a cabinet, to help convey this. Art for Munch isn’t meditative, intended to help us reflect or take stock, but to capture moments as they hit us.

Yet it’s as much about the way it’s painted. It took him a year to complete, working it over and over. Take the oppressive downpour of those persistent strokes of deep green. The mother’s body seems to disappear into them, as much as the child’s pallid face does into the white pillow. Which spells out the whole story, unbearable but unavoidable parting, the mother trapped in the weight of this world just as the child fades out of it.

Munch’s father was a doctor, and the painting’s based on a child he saw treated for TB. Yet both his mother and sister died from the disease, while another developed schizophrenia. He came to believe that “disease and insanity were the black angels that stood over my family”.

But that merely instanced it. If this was a time when medicine was less advanced, where sickness seemed able to strike at will, it becomes so strongly and persistent a theme of Munch’s that it seems inadequate even to call it a perennial threat. It seems at the very heart of things. It runs right through nature, long held as the source of health. And so society cannot escape it…

Each Confined Within Themselves

Munch associated with the Kristiana Bohemians, described by the British Museum as “a group of bohemian writers and artists who sought to expose the anxiety and hypocrisy beneath society’s ordered surface, including a fear of sexuality and its consequences.”

Which we might well see in ’Angst’ (1896, above). Unlike the isolated figure of ’The Scream,’ respectable Sunday finery pulls the figures together into a black clump. (Something we also see in ’Death in the Sick Room’.) Yet their expressions while matching are mournful in their solitariness, a parade of ghouls each confined within themselves. Munch commented “I see their hollow eyes, skulls behind the pale masks.”

Yet when he depicted his comrades, as in ‘Kristiana Bohemians II’ (1895, above), these are far from the free spirits commonly thought of. Instead, in one of the most funereal party scenes in art history, they’re poor lost, pitiable things. They’re as angsty as the figures in ’Angst’, they’re just being angsty in a bar rather than on the way to Church. That’s thought to be Munch’s cheery visage, puffing away in lower left. And, at a distance but under the smoke from his fag, lurks a femme fatale if ever there was. The show identifies her for us (Oda Englehart), points out that a tempting bowl of fruit lies just below her and fills in the biographical details. But you’ve already guessed.

We’re told “Munch’s bohemian love affairs were frequent and beset with difficulty. He was attracted to women, but was unable to commit himself to anybody.” Suggesting the show’s title gets things the wrong way round. Fearful of both attachment and isolation, small wonder he became reclusive in later life. And while his bohemian brethren may have exposed the fear of sexuality, they articulated rather than dispelled it.

And this is bohemianism in a nutshell. Their revolt wasn’t entirely abstract and inconsequential. Hans Jaeger was banged up for sixty days for expressing deviant beliefs. Yet lacking any coherent or systemic critique of power (which would have involved questioning rather than just rejecting their bourgeois origins), bohemians become superstitious of it - fearing it’s tendrils wherever they wandered.

Why are these tropes so common? Why would women be presented as such powerful forces in so male-dominated a society? The question becomes self-resolving. In a world established as about predators and prey, the predator always fears the tables turning. Should women gain power it’s assumed this would not be over their own lives but over men’s. So in a work like ’Jealousy’ (1896, below) it’s assumed the woman’s motive isn’t attraction to the second figure, who is barely delineated, but to stir up jealousy in the first. Her life is about its effect on his. We even see his despairing reaction before its cause.

But that’s not the whole picture. Look at ’Attraction’ (1896, above). It’s like two energy vampires got together, and each is able to suck the essence from the other but without gaining sustenance - a feedback loop of mutually assured destruction. A desolate road stretches out ahead of them, spelling out their fate. You imagine each is aware this will happen, but neither can change their nature enough to break from it.

But ’Desire’ (1898, above) breaks the mould most of all. A young naked woman is laid out as if on a slab, with three malevolent male heads leeringly hovering over her like cruel apparitions. As if all they are is bulging eyes and devouring mouths. The nebulous black wash replacing any kind of a background makes the effect starker, as if we’re witnessing some primal sacrifice played out as a universal event.

Given his family history connection to ’The Sick Child’, this is perhaps the only work we’ve looked at were Munch is definitely not the subject. But even when defined more tightly, much of Munch features himself or fairly transparent stand-ins pushing their way into the foreground. An artist’s work may have to be about himself to some degree, but it also needs to involve us or it becomes a closed system. And this is the central question which hovers over Munch, perhaps over the whole of Expressionism, packed inside the paradox of ’The Scream’.

No comments:

Post a Comment