“We are human beings, our greatest obsession is with ourselves.”

- Bacon

The Self As A Moving Target

First off, don’t go thinking this is the equal of the Tate retrospective. Then again, that was fifteen years ago so this is the easier show to see now. And it has its moments of insight, as we’ll see…

For a story which gets so messy, with so much paint slathered across canvases, it starts off with surprising neatness. Post-War British art was dominated by Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud, with their return to figuration. Spurred by Freud’s first solo show and Bacon’s ‘Three Studies For Figures At the Base of a Crucifixion’ both in ’44.

And the two were friends. Freud’s wife is quoted commenting that they met for dinner almost every day, and often for lunch too. Yet they were similar the way bookends are, as complimentary opposites. Freud worked slowly, obsessively and always from life. Bacon tried that, but soon gave up on it. A trivial-sounding detail which becomes a thread to keep tugging at.

When he did use models, he normally brought in friends. Yet he was soon asking for them to be photographed instead. Even for his many self-portraits. He worked from photographs when painting the cast of William Blake’s head, despite owning a copy of it. He repeatedly worked on, in his phrase, distorted records, of Velazques’ ’Portrait of Pope Innocent X’ and Van Gogh’s ’Painter On The Road to Tarason’. But from reproductions, he never saw the originals. (In the latter case, it had been destroyed in the War, only reproductions existed.) Not the normal artist’s impulse.

And let us not forget the New York School were at this same time creating a style or art which they thought could hold photography at bay. Bacon’s instincts took him in the opposite direction.

One reason is a combination of collage and mutation-through-reproduction. After that first mark on a cave wall, all art has existed in the context of its influences, so in some way has been a reply to them. But with mass media this became more and more prevalent. The more that had already been said, the less and less could anything be added which wasn’t some sort of reply. It was in this context that Bacon chose to make his images from already existing images.

He kept a large, (and characteristically disordered) collection of photos and reproductions, from all sources - torn from the pages of art books or clipped from newspapers or cheap magazines. One photo (from 1950) shows some of these laid out on his studio floor, jumbled and paint-splattered, high art, history and nature studies thrown in together. It doesn’t look far from a Paolozzi collage of the same era. And from much the same motives, to break down creative hierarchies.

But there’s a bigger reason…

The show is full of photographs, to the point you can’t help but think a few more paintings might have been an idea. But that might well be how he wanted it, for he cultivated images both of himself and his studio (with its legendary messiness). They’re almost a part of his art, as much so as if he’d been a performer.

And none of his paintings look exactly like either of these. But they look quite like both of them, there’s a familial resemblance. Even if we say there’s only motion blur because the photo “went wrong”, only a photo would “go wrong” like that. Photography had its own visual vocabulary, which painting could borrow like languages use loanwords. There’s a looser, more fluid approach to imagery which photography had enabled.

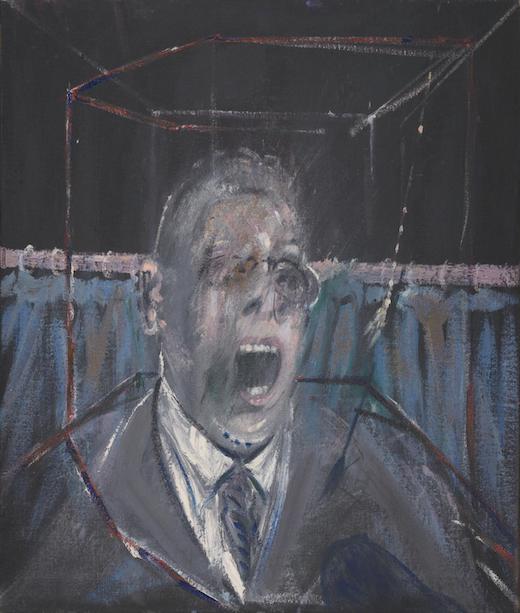

The shows says shrewdly that he sought to “exploit our familiarity with the traditional portrait form to shocking effect.” Because we know how portraits work, don’t we? For much of their history they were there to convey status, launder the reputations of usurpers and embezzlers by placing them loftily on the wall. Inevitably, they were still- in the way hieratic art was still.

Bacon’s figures are plasticated, amorphous, sweeping curves of paint which neither go abstract or quite resolve into a face. Portraits are supposed to be adjacent to still lifes. Bacon’s figures seem to shift before us, slithering, ungraspable. We’re not the stuff of statues, we’re protoplasmic. Many have words like “study” in the title, like they’re unfinished and quite possibly unfinishable. Just look, for example, at ’Portrait of Man With Glasses III’, (1963) below.

And if the portrait had to some extent been democratised in previous decades, we still assumed our identities were fixed. After all, above all things, we know who we are. Yet there’d been what David Bowie called “that triumvirate at the beginning of the century, Nietzsche, Einstein, and Freud. They really demolished everything we believed. 'Time bends, God is dead, the inner-self is made of many personalities’.” Bacon was using modern methods to convey a modern theme, while using his chosen genre to exploit the discrepancy between modernity and tradition.

It All Comes Into Colour (But Black and White Was Better)

Early Bacon wasn’t just monochrome, it was so murky you peer into his paintings like darkened rooms. When colour is used, it's not too different to spot colour in printing. You are often unsure what are objects in space and what are lines representing psychological states, like those wiggly lines in cartoons which represent anger and so on. Take 'Study For a Portrait’ (1949, below).

But by the early Sixties that had started to change. Works become bigger and brighter, as if someone just hit the light switch. Sizes enlarge and the figures correspondingly shrink, become more situated in a ‘real’ space. See for example the couch potato in another ’Study For a Self-Portrait’ (1963, below).

The show is laid out to present this as if its Bacon coming into his own. The first section is essentially a long corridor, which you travel through to arrive into a bright and spacious room. Except I feel precisely the opposite. There’s a nightmarish quality to the earlier works which is banished by all this light.

About the same time, he started to paint and re-paint a relatively small group of friends. (The show puts this down to the death of his lover Peter Lacy, in 1962.) And this large room is divided into sections, devoted to each of these. Which isn’t the way to go. It may have worked for Freud, but not here. The portraits don’t differ in style or imagery very much, their subject is more the person holding the brush than the one smeared across the canvas. Rather than his chief motive being fidelity to his subjects, he could switch from one to another mid-portrait. Bacon’s art at its best was universal, more than particular.

As Laura Cumming points out in the Guardian: “Likeness is almost beside the point… If it weren’t for the photographs threaded through this show, could you really tell [these subjects]? The one recognisable face is Bacon’s own.”

Except there’s one glaring exception to this rule, and that’s George Dyer. Their relationship was tempestuous to the point of violence, but he seems to have been Bacon’s great love. The show saves for its finale the 1973 triptych which portrays his suicide. But perhaps more interesting is ’Portrait Of George Dyer In a Mirror’ (1968), which looks like multiple images of him scalpel-bladed together. The presence of the mirror suggests truth, and recalls Bacon’s comment “no matter how deformed it may be, it returns to the person you are trying to catch.”

Overall, the image suggests Bacon was divided whether to capture or obliterate him. The flying flecks of white paint are added to other Dyer portraits and, as far as I could see, to no others. There’s little avoiding the suggestion that someone has been jerking off to this disturbing scene.

And there’s other upsides. An early work, ’Study For a Portrait’, (1952) was based on the well-known still from Eisenstein’s film ’Battleship Potemkin’ (both above). But while the broken eyeglasses remain the figure is swapped from female to male. Bacon’s earlier era was in general very male-dominated. Which, when combined with its themes, does start to stray towards man-painy. While in the later portraits women feature more. The poster image, for example, is of Muriel Belcher (up top).

Then there’s the small heads…

Most of Bacon’s paintings of this era were on an almost monumental scale. But at the same time, as the name might suggest, the heads aren’t even life size. With the show arranged around subject model, again and again these are hung adjacent to the large paintings. They look almost like punctuation marks between words. But you notice it quickly - the smaller is the better. See for example ’Three Heads of Muriel Belcher’ (1966, below). The poster image is the middle one.

The heads are normally arranged in triptychs like that, sometimes diptychs. And they look to me like they were composed together, with the combination in mind. (I hve no way of proving that. But that’s how they look.) They’re not sequential, like a mini comic strip. But when the individual images suggest movement anyway, lining them up like this enhances the sense. The eye’s movement across them comes to suggest movement within them.

At the time, that old Tate show seemed pretty comprehensive. So it must be a tribute to Bacon that there was more to say about him.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

%20copy.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment