“Johanna may not even be real. But she is an addiction”

- Rolling Stone

The finest songs are not always the most immediate. I doubt if anyone in 1966, on first hearing Bob Dylan's new album 'Blonde On Blonde’, thought of 'Visions of Johanna' as the stand-out track.

First you needed to cope with yet another of Dylan's turns of direction, from the abrasive electric sound and venomous in-your-face surrealism of the previous year's 'Highway 61 Revisited'. That had been definitively Northern – urgent, brimming with attitude – while the Nashville-recorded 'Blonde' could not have sounded any more Southern, languid and brooding. Some tracks even gave woozy New Orleans jazz a look in.

But even then 'Johanna' must have sounded strangely closely to the country station it disparaginly describes, the one that “plays soft, but there's nothing really nothing to turn off”. It couldn't be any further from the epic swoops and rolls of the next number 'Sooner Or Later', the only track on the album to have survived from the original New York sessions. And yet what didn't arrive with a fanfare lingered, and is now one of Dylan's most celebrated songs.

Perhaps that could be something to do with the air of mystery which Dylan characteristically stirs up. “Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial”; “Jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule.” You could probably throw a dart at the lyric sheet and come up with something similar. It all sounds so vivid, like it should mean something, but trying to figure out precisely what can result in a whole load of headscratching.

Perhaps to try and pin down the cascade of images is a kind of category error. Robert Shelton wrote in his Dylan bio ’No Direction Home’ “the nonsequential visions are like a swivelling camera recording a fractured consciousness”, and he went on to quote Fowlie on Rimbaud, on a poet “bent upon subordinating words to their sounds and colours”. Dylan himself had earlier written: “To understand you know too soon/ There is no sense in trying” and was scornful of those who thought themselves able to interpret him.

Would the facts help any? Dylan almost certainly wrote the song while on honeymoon with Sarah Lownds in New York in the winter of 1965/66. And yet this isn’t exactly a love song. Which has tempted some to speculate that he wrote it pining for an earlier paramour, Joan Baez. The present Louise in the song thereby becomes a stand-in for Sara, contrasted against the absent but longed-for Johanna, aka Baez. (Though some claim the earlier ’Like A Rolling Stone’ was a put-down of Baez.)

Of course I have no more idea than anyone else whether this is true or not, but there may well be something in it. Firstly, when you hear sections of Dylan fandom hating on Baez so badly, in a manner reminiscent of Beatles fans on Yoko, you almost want to take it up just to spite them. But more importantly, Norman Mailer's theory of Picasso was structured around his relationships, embarking on new styles to capture each new lover, then all over again to decry them as he tired of them. And Dylan is in many ways the Picasso of music. For example, his earlier break into his trademark 'protest songs' came at least in part through the influence of an earlier girlfriend, Suze Rotolo. (Pictured with him on the cover of the 'Freewheelin' album of 1963, which launched that style.)

Except, as ever, the main problem with this biographical reading is that its just that – a biographical reading. Your interest flickers to hear the line “the ghost of 'lectricity howls in the bones of her face” after finding out that New York had that winter suffered a power blackout. Or that the song was originally called <i>'Freeze Out'</i>. But really, where does it take you? It's a bit like finding out where a film director used for a location shoot, or an artist for a painting. At most you're describing the impetus of a work, rather than the work itself. Ultimately, reducing “the ghost of electricity” to a power cut seems... well... reductive.

As Andrew Rilstone has said “I don't think that Bob set out to tell a naturalistic story... but decided, for some reason, to present the story in the form of a riddle.” To which we might add, when Dylan had earlier broken up with Suze Rotolo he didn't think himself as above writing a perfectly straightforward account of the whole affair in 'Ballad in Plain D'. (Much to the disdain of her sister, who'd been savaged while virtually named outright.)

Okay, you might well ask, so what is going on?

A common theme of the album was 'strandedness', referred to specifically in many tracks such as 'Temporary Like Achilles' or 'Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again', and ever-present in the more languidly paced music. But the theme is perhaps at its most developed here. Note the two separate references to keys, jangling uselessly in this inescapable situation. Note the second line “we sit here stranded, though we're all doing our best to deny it”.

“All” makes it seem a crowded song. But, befitting the feeling of confinement, I contend there's only three characters to the story – and one of those is conspicuous by her absence. All the others – the ladies and the watchmen, the pedlar and the countess – merely collapse in on one another, like alter egos invented to distract you from your loneliness. (Or perhaps bystanders, a watchman seen through the window who has a character projected onto him. It scarcely matters which.)

Before we get to Louise and Johanna, let's start with the third-named character:

”Now, little boy lost, he takes himself so seriously

He brags of his misery, he likes to live dangerously”

Remind you of anybody? Little Boy Lost is starting to sound like a straw-man parody of Dylan himself. And after slagging off pretty much everybody he knew, plus a fair few innocent bystanders, why not give himself a turn?

Now the alert reader at this point is probably thinking there's a fourth character in the song.I f Little Boy Lost is Dylan, then just who is the unnamed narrator? And I'll concede things might seem that way.

”Just Louise and her lover so entwined

And these visions of Johanna that conquer my mind”

Then again, perhaps not. Little Boy Lost most likely is the lover getting it on with Louise. But I'm suggesting Dylan is simultaneously the body entwined with Louise and the mind thinking of the absent Johanna. He feels so disconnected from the picture he's in that he conceives of himself as two entities – the present body and the removed, preoccupied mind.

Johanna is a religious name – it means the grace of God. If you look Louise up, it means warrior. But you might as well go and forget that second part, for it's not really got much to do with the song. I suspect Dylan just picked the most regular and the most out-of-ordinary names he could think of. I must have met many Louises in my time, I'm not sure I've known one Johanna.

And the distinction between them is all there in that early line...

”Louise, she’s all right, she’s just near...

But she just makes it all too concise and too clear

That Johanna’s not here”

Something many people seem to miss is that, unlike many a Dylan song, he's not actually disparaging about Louise. “She’s alright... she's delicate and seems like the mirror.” He quotes her saying “Ya can’t look at much, can ya man?” as if she's being perceptive. But the point about Louise is that she's merely present, just as Johanna is defined by her absence. They divide much as Little Boy Lost and the narrator are split.

Clinton Heylin has suggested that Dylan, suffering from writer's block at this point, has made Johanna his absent muse. And lines about Mona Lisa with “the highway blues” would seem to go along with that. But this seems only marginally less prosaic than the earlier romantic triangle notion. Dylan may have got there through cold feet about a marriage, or deciding to write a song about not being able to write a song. In the end, the how of it doesn't really matter.

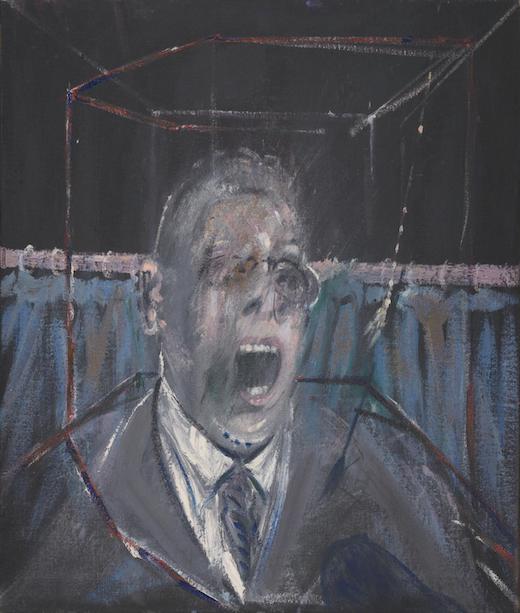

In a word, it's purgatorial. The song is about separation, about the body being exiled from the spirit. At the end of the song, rather than having Johanna show up, everything else goes away – leaving only her absence.

”And Madonna, she still has not showed

We see this empty cage now corrode...

...the harmonicas play the skeleton keys and the rain

And these visions of Johanna are now all that remain”

Coming soon! While we're on the subject of Dylan...

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

%20copy.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)