”I paint as I see, as I feel. They also feel and see like me, but they don’t dare. I dare.”

-Cezanne

The Dissident Impressionist

When a young man, Cezanne was told by his banker father to abandon his foolish art aspirations and start studying for a respectable career in law. At the same time his best buddy, the radical writer Emile Zola, suggested he join him in Paris. Now, we know how this sort of thing goes. We are already suspecting that it is not eleven rooms of neatly ordered legal papers which lie ahead of us. And indeed, in 1861, at the auspicious age of twenty-one, he did indeed leave his home in Aix-en-Provence for Paris and Zola.

But ultimately, he chose not to choose. Never what you would call a team player, after less than a year he’d left Paris too, and split pretty much the rest of his life between the two places. This cemented him as intellectually as well as literally peripatetic, self-isolating, beholden to no other. He was a paradoxical combination of cantankerous and curmudgeonly, wilfully argumentative while at the same time a recluse who shunned, if not the ways of men, the world of art as much as he could. He fell in with the Impressionists early, exhibiting at their very first group show in 1874. But from then he only appeared in one further. (The third, from a total eight.)

’Rooftops In Paris’ (c.1882, above) neatly demonstrates this by giving up nearly half of the frame to a single angled roof. It’s less of an element in the picture than a barrier placed in front of it, suggesting that even when the artist was in Paris he was never really in Paris.

Early Cezanne, it’s easy to forget, looks almost absolutely unlike his mature style, with paint often slathered on with a palette knife. The show describes this era as “dark, brooding, violent.” (And suggests he was at this point most influenced by Zola’s writing.) He called it Couillarde, which critics and shows take delight in explaining means “ballsy”. Much of it, it’s true, is juvenalia. In fact it’s often literally juvenile, hyper-heightened dramatics - as if he’d gone through a teenage Goth phase. The show seems embarrassed by these, giving only a couple of examples. But in truth, there’s good stuff in among them.

’Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup’ (1865/70, above) is an example of that rare genre, the ballsy still life. There’s a collision between form and content which makes it involving. The objects are painted in such an intense way, then set against a near-black background, that it feels like rather than simply there they’re asserting their presence.

Landscape In Doubt

From 1870, Cezanne was living at least part of the year in L’Estaque, on the south coast. And quite frequently painting nature scenes en plein air, just like a regular Impressionist. But take 'The Bay of Marseille Seen from L’Estaque’ (c.1895, above) and mentally hang it next to a Monet landscape. In fact why don’t we pick the Monet seascape, the one that gave the school its name, 'Impression, Sunrise'? They don’t look like brothers in arms, they look worlds apart.

First, Monet’s vivid use of colour, so integral to what we now think of as Impressionism, is replaced by something much more muted. (On-line, Cezanne’s paintings are often artificially brightened, seen as an error that needs correcting.) More crucially, as we’ve already seen, Monet’s subject wasn’t objects so much as moments, his method to capture fleeting changes of light and weather. To Cezanne, such things were just an encumbrance. Not only does he give us no clues as to time of day, we can rarely guess what season it is. (It’s often suggested he preferred Provence because of its lesser seasonal variation.)

His work is more delineating, more dispassionate, even clinical. There’s no particular focus of interest, the whole view faithfully depicted in paint, with no more favour than a map-maker would show. Not a record of a fleeting moment, more of a summary. Unlike his view of Paris shown above, there’s no formal barrier between us and the landscape. But it still feel distanced from us, an object for examination. We know that Monet painted rapidly, and Cezanne deliberatively. He used small, diagonal ’constructive’ brush strokes, much more regular and even than Monet’s dabs. Look at some of those spanning dates given behind his paintings’ titles. He could hang on to works for years, and died with many still officially finished.

Also, Cezanne’s father may have issued plentiful orders but also left his son privately wealthy. So he had no financial incentive to be as productive as Monet, something he took full advantage of. Richard Verdi states “only thirteen works of Cezanne’s maturity were accorded the distinction” of his signing them. (Disclaimer: Cezanne was closest to Pissarro, whose work is less distinct from his. But Monet is the go-to Impressionist for most.)

Two terms almost impossible to avoid using over Impressionist art are verite and joie de vivre. They’d paint flaneurs perambulating around Paris, with the sense that they could at any time swap places with the figures in the frame. While with Cezanne there are no figures in the frame to be bothered by swapping with. Not even those diminutive dash figures so often used to convey scale.

Though I’ve started off with a view which is very Cezanne, they’re not all quite as distanced. ’The Sea At L’Estaque Behind Trees’ (1878/9) has a Parisian-like barrier before us. But those trees transform what would otherwise be quite a similar work to ’Bay of Marseilles’. By inserting themselves between us and the view, they give more of a sense of composition and involvement. They create a contract between their twisting and and the rigid geometry of those roofs and (especially) that jutting chimney.

While ’Chestnut Trees At Jas du Bouffan’ (1885/6, above) also uses trees to create compositional order. It’s not just their even spacing. In the lower half, the verticals of the trunks are echoed in the other straight lines of the farmhouse and wall, if at times at right angles to them. But the contoured mountain appears just as the trees break into branches, with the result the trees at once divide and unify the composition. While, from this perspective, the rugged mountain is the same heigh as the two buildings, creating another compare and contrast.

The mountain is Mont Sainte-Victoire. Cezanne painted twenty-nine portraits of his significant other, Marie-Hortense Fiquet. (One is coming up.) A high number, until you consider he painted that mountain no less than eighty times! He read books on it’s geology, the way a portraitist might get to know the backstory of his subject, and in 1902 even moved his studio nearer to it. What was it’s fascination for him?

The later work ’Mont Sainte-Victoire’ (1902/6, above) may answer that. It’s all something of a blur, particularly the foreground. But it’s not like Cezanne came across a blurry image, from a moving train or on a hazy day. This is more like a rough sketch, where lines are tentatively filled in then shifted, then transposed to the painting exactly as they are. Or more like several rough sketches, all combined into one. It’s not the result of a process, it’s the record of a working out.

What could be more of an unchanging fact than a mighty mountain, dominating the horizon? But how well do we truly see it? Is it even possible to capture it on canvas? Isn’t the more honest method to record our continuing failed attempts? In this way the mountain became his white whale.

The show describes his approach to painting “as a process and investigation, where uncertainty plays an integral role.” Robert Hughes is more poetic: “Cezanne takes you backstage...The Renaissance admired an artist's certainty about what he saw. But with Cezanne...the statement ’This is what I see,’ becomes replaced by a question: ’Is this what I see?’ You share his hesitations about the position of a tree or a branch; or the final shape of Mont Ste-Victoire, and the trees in front of it. Relativity is all. Doubt becomes part of the painter's subject.” Cezanne’s method is not about dazzling you with sights, but whispering doubts in your ear.

An Apple For Art History

You can read everywhere about how Cezanne took to still lifes in order to upset the traditional hierarchy of the arts. And there’s little doubt he exulted in that. A famous quote, stuck up on the wall in this show, is “with an apple I will astonish Paris!” But the crucial point is why they were held in so low regard. Which was because they gave little opportunity for either narrative or symbolism, widely regarded as art’s positive and enduring qualities.

With ’The Basket of Apples’ (c. 1893) the basket isn’t just upturned, it’s angle is emphasised by being set against the upright bottle. Added to the white cloth pushed so far in the foreground, and the effect is as if those apples are tumbling out at us. In fact, this ‘still life’ seems a lot more dynamic than may of his landscapes!

Though there’s other reasons. Richard Verdi is probably right to say still lifes partly appealed because in the studio he could control all conditions. (Though even then he could take so long the fruit would start to rot.)

I overheard one punter asking what the apples represented. Which is the wrong question squared. Cezanne is not interested in the apples as apples. To him, the fruit, the bowl, the bottle, all are mere props with which to create form. He’d return not just to these themes but the very same objects, repeatedly, until familiarity stops us noticing them for their own sake, reduces them to elements in a composition. (Picasso and Braque played a similar trick with their short-list of objects used in Cubism.)

And so two contradictory-sounding things are true at once. There’s no great difference between the way he looks at his stiff lifes and his landscapes, they’re both objects of contemplation from which the artist is distanced. Mountains and baskets, bottles and chimneys, apples and cottages, they take on an equivalence. And also, the essence of Cezanne lies in the still lifes. (See up top how they make it into the poster image.)

Even without the title, it’d be clear what the main figure was in ’Still Life With Plaster Cupid’ (c. 1894, above). But here the mini-statue isn’t treated as one more decorative element, as if the pitcher had the week off, the composition is centred around it as if a portrait. Which seems something of a statement, if not an active taunt, rubbing the viewer’s nose in the fact these are not figurative works.

But what we really need to talk about is that table. Nothing has been slipped in your drink, it actually looks so sloped and bent. Then has one solitary apple placed at the end of it, as if atop a slide which it is somehow not rolling down. Yet the foreground is so accurately painted we take a while to notice, we instinctively trust the artist to portray pictorial space ‘correctly’. There’s the second figure at the end, which we come to realise isn’t another statue but a painting within the painting. Then there’s the second frame on the left, forcing us to ask what there is painting-within-painting and what is still life object?

Cezanne does this sort of thing all the time. And he does it to mess with you. To play games with you, to undermine your confidences, to slyly undermine the rules of art you normally take as read. (And the degree to which he took personal delight in being confounding shouldn’t be underestimated.)

One Foot In Arcadia

It’s curious that Cezanne was the Impressionist who most pioneered Post-Impressionism, yet also the one most indebted to Classicism. But to him the timelessness of Classicism, so at odds with the Impressionist drive to capture the moment, appealed. Along with its sense of overarching order. (Which, with typical perversity, he at once pursued and questioned.) This is most evident in his series of Bather paintings, which include the largest work in the show - ’Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses)’ (1894/1905, below).

With everything so idealised, with such disinterest in evoking a real place, the doubting Cezanne essentially disappears. For once, we know just what we’re looking at. And the ditching of ‘difficulty’ seems deliberate, for these were the works which Cezanne wanted to be remembered by. Verdi says they were “clearly intended as his artistic testament.”

The trouble is, it’s not good. Not at all.

You can see the thinking. Bathers lack the clothing or other trappings which would tie them to one time period. So they make the ideal subject to combine Classical and Modern themes. But the figures don’t convince as figures. The seated one on the left looks like a sack of flour, strangely sporting a head. Yet neither do they reduce neatly to elements in a composition, the human equivalent of those bottles and apples. Cezanne has one foot in Provence, the other in Arcadia. And it leads to an awkward stance.

Yet these works were popular, including among other artists. Matisse bought one when he could little afford it, and made his credo “if Cezanne is right, I am right.” Now Picasso’s inheritance from Cezanne seems clear enough. There’s twin tracks of it; first Cubism took a similar analytically questioning approach to subjects, and later he took up a similar Neo-Classicism. Matisse’s debt seems harder to discern. Even more than Monet, he was known for his rich and vibrant colours. Colours he delighted to find in the Mediterranean, colours Cezanne stood in front of and disregarded.

But squint at it and it all comes into focus. Cezanne has aligned his figures with the landscape. Look for example at that leftmost angle. Which has it’e echo in Matisse’s ‘Dance’ (1910), where the figures are shown in such abandon they have almost lost individuation, while their surroundings reduced to two simple colour blocks. ’Bathers’ occupies an interchange between more regular depictions and Matisse. Perhaps at the time a necessary one. Yet by the time we get to Matisse it’s just a stepping stone across a river, which we’ve no need to step back on after we’ve crossed. As ever, the peril of being ahead of your time is that time won’t keep you there forever.

The better works here are the ones Cezanne has less grandiose plans for, which he probably regarded as ancillary, such as ’Boy Resting’ (c. 1890, above). The casual pose suggests this figure could get up and walk away, as soon as he chose to.

Friends, Relations, Gardeners

So does this show that Cezanne had a problem with the figure, a stumbling block he was better of circumventing? Nope. In fact, nothing about him could ever be so simple. In fact he could excel at portraits.

’Madame Cezanne In a Yellow Chair’ (18880/90, above) is of Marie-Hortense, as promised earlier. It’s hardly an ostentatious or attention-grabbing work, but a supremely effective one. Her face is more iconic than ‘realist’, yet perhaps for that reason conveys a great sense of self. Accounts usually focus on her inscrutability, those narrow features enhanced by being set in the highly rounded head, the eyes looking off. But that inscrutability can only come through her sense of presence. Much as with his other subjects, he returned to the same few sitters - family, friends or workers on his father’s estate.

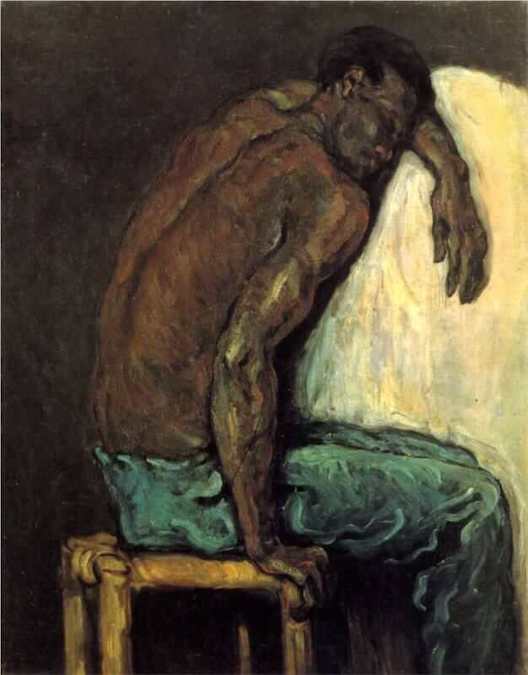

’Scipio’ (1866/8, above) is portrait enough to be named after its subject. But it seems pitched to occupy the impasse between portrait and narrative painting, with it’s figure largely turned away from us. With the emphasis on his physicality yet stillness, the mood is one of weary rest. And of course at this time black people would have been very much associated with physicality. The white… well, whatever that white thing is that he’s leaning on seems there to emphasise his blackness.

So is this, as has been suggested, an anti-slavery work? Perhaps. But we should forever be cautious about reading into art what we want to see. Despite his association with the radicals Zola and Pissarro he was mostly silent on political questions, allowing us to project our wants onto him.

Sombre Still Life

By the late Nineteenth century, Cezanne was becoming increasingly plagued by ill health. At which point many of the themes of his early years return, but with a twist. The young man’s thrilling sense of dalliance with death is replaced by an old man’s sense of grim inevitability. What was brooding and violent becomes sombre.

Compare 'Still Life With Apples and Peaches’ (c. 1905, above) to the earlier ’Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup’. The colour scheme, the paint style, all is less in your face. And yet while it’s closer in composition to his mature still lifes, it seems nearer in mood to that early work. It’s as if all the elements are the same as he’s been using, save for Cezanne himself, whose older eyes now see in more sombre colours. The contained white of the cloth seems there just to set those colours off.

An Artist For Artists

As we’ve seen both Matisse and Picasso owned works by Cezanne. A list to which we should add Monet… yes the Monet we’ve sent so much time contrasting him from. And he continued to appeal to later generations of artists, including Gauguin and Van Gogh, and - some time later - Henry Moore. As the show says, he’s an artist’s artist. And you can see why. Some artists close off a direction simply by occupying it, straddling it until others are forced to detour around. Cezanne, who always posed questions and foregrounded problems, was the opposite of that.

Yet, whenever anyone is called an artist’s artist or musician’s musician I’m tempted to ask - all very well, but what about the rest of us?

Cezanne himself said he was influenced by the Realists. Who, as mentioned before now, are normally written out of popular art history, their existence challenging the popular myth the Impressionists arose from nowhere. (The indicia here has a particularly absurd sentence claiming art had been unchanged the past four centuries before Impressionism.)

True, the art isn’t the same, but the tone is. There’s a dourness to it, a sense of thrusting the truth in the publics’ face and demanding they look. Their truth was (more or less) political, while Cezanne’s is that we cannot claim to know the truth, but the effect is the same. Aesthetic appeal is seen as a distraction, painting exists to prove a point. A sign you can tap, only done in oil.

And this line continues. You can see the roots of Cubism in Cezanne, clear as day. It’s already budding in those neat, angled little brush strokes of his. (And Braque, Picasso’s co-conspirator in Cubism, praised Cezanne just as much.) Which, of all the well-known Modernist movements, was the most formalist, most concerned with questions around painting, the conventions used to convey objects, and so on.

And Modernism was concerned with such questions, inherently so. Anything that wasn’t simply wasn’t Modernism, by definition. Yet Modernism was also concerned with the modern condition, and how changed times might be reflected in changed art. Impressionism was deeply concerned with this, even if that’s part-obscured by hindsight. It’s central paradox was to create paintings which were unambiguously painted, with brush strokes entirely recognisable as brush strokes, which were still of something. Cezanne’s paintings are primarily paintings, his primary subject art and representation.

And without this second half of the equation Modernism soon becomes dry, hermetic and uninvolving. The reclusive Cezanne seems pitched on the edge of this abyss, falling in, pulling himself out, falling back in again. And it’s consequently almost impossible for those of us who aren’t artists not to have a love/hate relationship to his work. Art should interest the viewer, yes. It should be more than merely decorative. But it should also appeal.

(Just in case anyone’s wondering, why does his formalism bother me more than Giacometti’s? After all, both are about constantly re-positing the most essential questions of art. And I’m not sure I’ve much of an answer. Perhaps because Giacometti’s white whale was the human figure, not an apple or a distant mountain. So there’s always a subliminal association between his capturing the figure and getting to know the person.)

Yet Cezanne fits well into art histories, particularly those which reduce to simple flow charts. An original Impressionist who went on effectively found Post-Impressionism? An artist particularly interested in art theory? Those who see their job as telling us about art are likely to be telling us about Cezanne before long. This prestigious Tate show is thick with punters. But had his name slipped from art history and now needed re-inserting, if this show was the first people were seeing of him, would he then prove so easy a sell? Like Cezanne himself before a subject, I remain skeptical.

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment