Written by Mervyn Haisman & Henry Lincoln

Plot spoilers! And not just for this story! (Maybe just skip this one if you don't like plot spoilers)

”Why does someone wish harm to the monks of Det-Sen?"

- Khrisong

Making The Yeti A Threat Again

After Atlantis but before Loch Ness... it was inevitable the Abominable Snowman would show up on ’Who' someday. The hirsute fellow was a surprisingly late addition to the Western canon of folk monsters, due to the relatively late exploration of Tibet. Though longstanding in local folk mythology, he didn't gain his more dramatic stage name until acquiring an English agent in 1921. ('Yeti' in Tibetan means simply 'bear of the rocky place'.) He was in short one of the last wild things to be hunted down.

And it wasn’t really till the mid Fifties that his career truly took off, with salacious newspaper reports on Himalayan expeditions. (Even his name was coined by a journalist, Henry Newman.) These soon spread into films, with the Goons parodying the phenomenon (with ’Yehti’) in ‘55. From there he became ubiquitous, appearing in the central cast list of monsters in films such as ’Monsters Inc’ (2001), because he couldn’t not do.

Such stories were the latest iteration of a broader trope, which has resonance because of the ‘between’ nature of the man-beast. In folklore this creature often haunts the edges of towns, sneaking in under darkness. Neither fully feral nor human, his relationship to us is ambiguous. So we’re both drawn and repelled. More modern stories tend to be about attempts to seek him out, capture and categorise him, in an attempt to reassert order on the world. Which never, ever go wrong…

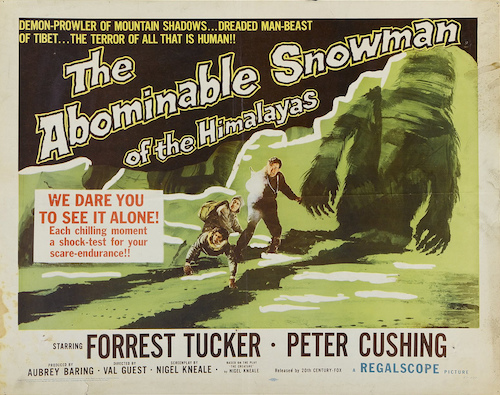

Yet this is more than a decade later and much of that had already been revised. In Nigel Kneale's 1957 film 'The Abominable Snowman' he twists the story by revealing the thing is not between but beyond, an all-wise being simply waiting out man's hubristic rise and inevitable fall, communing only with some Buddhist monks. The protagonist states “it isn’t what’s out there that’s dangerous, so much as what’s in us”.

Herge's 1960 comic album 'Tintin in Tibet' is less radical, but still imagines a sympathetic monster, capable of care, with a “human soul”, but misunderstood – in the mould of King Kong and Marvel's Hulk. But significantly both work in the other great cultural export of Tibet, robed Buddhism, manifesting ancient wisdom through the medium of Jedi mind tricks. And both rely on a Boo Radley ending, coming to the conclusion they're best off undiscovered.

Haisman and Lincoln faithfully reproduce many of Kneale's elements - the signifying footprint in the snow (despite a distinct lack of snow), the two Western parties who run into one another, the bumped-off hunter, the psi-powered monks and so on. However, after years of shamelessly ripping off Kneale like no-one was supposed to notice, despite his Yeti film being heavily borrowed from in the predecessor to this story, not only do they turn those elements into a whole new plot they seem to treat the original as a kind of canon.

By now the Yeti had been rehabilitated into fiction's equivalent of polite society. Here, even as it keeps that abominable title, it chiefly refers to its critters as Yeti and explains they're “timid creatures”. So it reverses the twist – it’s when they up and start killing that people get perplexed.

And if the Buddhism in these stories is similarly given a particular slant, perhaps that's standard. Westerners are often attracted to the exotic trappings of Tibetan Buddhism – the robes, the chanting and so on become spiritual bling. But at the same time they're less keen on its ascetic insistence on discipline. So they try to populate its form with the content of Zen Buddhism. (Which is actually Indo-Chinese.)

Being less doctrinal and more experiential, it appears more adapted to our individualised way of life. (Though whether they actually grasp any of that or simply read what they want into it is another matter.) In Herge's story, for example, psychic powers are personalised, the 'gift' of one particular Monk rather than part of the Monastery's teachings.

So if 'Who' has a somewhat schizo approach to Det-Sen Monastery, perhaps that's par for the course. It is a Monastery, with “strict discipline and self training”, and not some Tibetan equivalent of a hippy commune. But, this being a Troughton story, it has to double as the de rigueur base under siege. Which of course is a metaphor for the closed mind. So chief sentry Khrisong busily orders his underlings while still more busily distrusting the Doctor. “Let them meditate! Let them consult!” he cries in derision. “I will act!” You could call him trigger-happy, if he was armed with anything more than a stick.

The story even takes steps to avoid it's own natural get-out. As Yeti start attacking people you could imagine him reactively falling into a military mentality. Yet dialogue between other Monks seems there specifically to tell us that he's just that kind of person.

”Formless in Space... I Astral Travelled”

So if 'Who' has a somewhat schizo approach to Det-Sen Monastery, perhaps that's par for the course. It is a Monastery, with “strict discipline and self training”, and not some Tibetan equivalent of a hippy commune. But, this being a Troughton story, it has to double as the de rigueur base under siege. Which of course is a metaphor for the closed mind. So chief sentry Khrisong busily orders his underlings while still more busily distrusting the Doctor. “Let them meditate! Let them consult!” he cries in derision. “I will act!” You could call him trigger-happy, if he was armed with anything more than a stick.

The story even takes steps to avoid it's own natural get-out. As Yeti start attacking people you could imagine him reactively falling into a military mentality. Yet dialogue between other Monks seems there specifically to tell us that he's just that kind of person.

”Formless in Space... I Astral Travelled”

In a rare early example of retconning, the Doctor has not only been here before but is there to return a relic. He even knows its Master, Padmasambhava. (Or as Jamie calls him 'Padmathingmy'.) And 'old friend of the Doctor' is a pretty clear nod that this is a character to be trusted.

...which of course is exactly why we shouldn't. Because Padmathingmy has fallen under the psychic control of the Great Intelligence, a disembodied force seeking to make itself manifest. The Yeti are actually robots at his malevolent command.

Now, by this point in 'Who' history, mind control might seem somewhat hackneyed. We've already had it in 'Keys of Marinus’, 'Web Planet’ and 'The War Machines’ to name three. (In fact the beeping of the spheres which control the Yeti is quite similar to the Zarbi signalling in 'Web Planet'.) And of course it's hard to escape the notion that these are plain cheaper to stage. You don't even need the rubber suit, just tell an actor to put on his sinister voice and you're away.

Yet, as we've seen, all those Hartnell examples are about the separation of mental from manual labour. This time it takes Buddhism as a set of synonyms for Western psychology. The Great Intelligence, that’s a name the Ego would like to adopt. Its as if his achievements had led Padmathingy not to enlightenment but to a pride which then Bunyanesquely rears up at him – his ego manifesting as an alter ego. When it states proudly “I am much power!”, the formulation of words seems telling.

Or on the other hand it could actually be Buddhist after all. At least by the standards of this sort of thing. The Great Intelligence's plan is like nirvana in reverse, an incorporeal being desiring to get back on the wheel. Padmathingmy can be seen as stuck in the state between death and rebirth, which Buddhists call Bardo. Initiates are taught to surrender to this process, but some trap themselves by clinging hopelessly to what has gone before. The plot involves him living hundreds of years past his natural span, then at the end welcoming death as “rest” and “peace”. (Which would make for two stories in a row about accepting the inevitability of death.)

And of course retconning a prior connection between him and the Doctor establishes an equivalence between the two. When Victoria attempts to explain the Tardis to a novice monk, he counters that his Master's astral travelling is pretty much the same thing. (Though oddly Jamie later shushes the Doctor against mentioning their mode of transport.) A plot point is his concealing his presence from the Doctor, to avoid giving away that he's hundreds of years old. Just like… oh, you guessed.

And these suggestions permeate the story. When Jamie first sees the Doctor on the Tardis monitor in his Himalayan fur coat, he cries “beastie!” And the same fur coat leads the explorer Travers to claim it must have been the Doctor who murdered his buddy, and Khrisong to insist he has the Yeti under his control. (Right plot, Khrisong, wrong perp.) There's even the suggestion that in returning the relic the Doctor is on some kind of pilgrimage. Certainly it's his managing to achieve this task which convinces the Monks to stop leaving him out as Yeti bait.

Ghost Traps and Chains

And beyond the Tardis and astral flight, there's a fair amount of paralleling in the story. The Doctor takes two objects from the Tardis, the relic and an electronic triangulation device (to track the Yeti). A captured Yeti is held down by a magic ghost trap, but also heavy chains. (A double precaution a monk describes as “wise”.) It's very 'Who', his science and their religion merely one thing seen from different angles. But how does it play out?

In the finale, Travers rushes out to the mountain where the Intelligence is physically manifesting, armed with his gun. To no avail, of course. While the Doctor and his crew find a room behind the sanctum, literally the power behind the throne. It's full of machinery which they promptly smash up. To no avail either. After all, we've already seen how the GI controls them by moving Yeti pieces around a game board rather than by any mechanism.

But then they break a pyramid of spheres. Throughout, the GI has been represented by these geometrically pure objects, like they're the portal-like link between his Platonic realm and our world. The Doctor finds the spheres inside the Yeti early in the story, but initially dismisses them as too light to contain any mechanisms. Not the mountain, not the mechanisms. It's a neat final twist, there to tell us what sort of story this was. It's an inner story, concerned with the workings of the mind.

But it pulls the twist only by utilising its own contradictions. Why are the machines there then? Just as a decoy? Beyond that, why go to the trouble of building the robot Yeti at all? Khrisong's question up top is quite a good one. The intra-story reason seems to be to scare away those pesky interfering monks and explorers, but before the Doctor shows up no-one seems much of a threat. And why model them on a creature everyone knows to be timid? Perhaps if the GI had tried this in England he’d have frightened everyone off with giant robot squirrels. Beyond that, just how were the Yeti built, with what materials? We're told it took Padmathingmy many years, which poses time as a solution for lack of materials.

It's much like Wotan's War Machines. There's two separate stories, joined together only in a plan that defies coherence. Not only can you imagine the story working without the robot Yeti stamping about, at times they seem keen to show you just how it would work – through spiritual possession, levitation and so on. The monastery could seem to be haunted by 'evil spirits', the faithful being driven out. Or perhaps the GI could have animated the actual Yeti into attacking, just as he turns people into his thralls. But we have to have killer robots, because killer robots are the sort of thing you have to have on 'Who'.

While the equivalence between the Doctor, the GU and Padmathingmy seems not even undeveloped but merely hinted at. You expect at least an 'Exorcist' moment where the GI suddenly tries to possess the Doctor, but no.

The Curious Case of Victoria

After an introductory story in which she was no more than a plot piece, and a follow-up where she obligingly stepped into a death trap, this time Victoria's even dressed differently. Her explorer's trouser suit makes her look like a principal boy in a panto. And this time she does stuff.

Yes, actually does stuff.

Alas, it doesn't help.

She's driven by a new-found curiosity, first insisting to Jamie she wants to go exploring despite what the Doctor said. Then once in the Monastery she becomes intent on reaching the Sanctum, off limits even to the monks. Of course she's being plot driven. She gets in there to discover it harbours ill deeds, stumbling on a revelation rather than confirming suspicions. But her cavalier disdain for the customs of her hosts makes her look brattish, like space travel has finally given her her teenage years. And, in a story which otherwise gestures at Buddhist sympathies, it doesn't seem at all clear we're supposed to be bothered by this.

On Balance...

Buddhists are big on balance, and there's a balance to be struck here. The way the GI's intrusive force goes almost entirely unexplained makes for something more effective than the banal biography Moffat later gave him. But rather than striking right this merely becomes imbalanced the other way. There's some intriguing themes and images, but they tend to lie about undeveloped and disconnected on the surface of a standard adventure story. Overall, the closest cousin to this story is 'The Faceless Ones’. In many of it's themes it feels like a dry run for 'Planet of the Spiders', despite that coming so much later. You may be best off foregoing your 'Who' fixation and watching the Kneale film instead.

Further reading: 'How Buddhist is This Series?' In the first 'About Time' volume, Wood and Miles came up with an intriguing reading of 'Web Planet' based on a biography of the writer. In the second volume, they do a similar thing...

No comments:

Post a Comment