“It is not an image I am seeking. It is not an idea. It is an emotion you want to recreate, an emotion of wanting, of giving, of destroying."

Getting out The Dirty Linen

Louise Bourgeois’ life was so long and so remarkably productive that this exhibition, fills the Hayward with work produced when she was in her Eighties and Nineties. An era where her art incorporated textiles and “domestic fabrics”, including bed linen and items of clothing.

Her career was effectively launched in 1932 where Fernand Leger, then her tutor, told her she was at root a sculptor. Because her art is about the physical, and needs its own physical presence. She said herself “to me, a sculpture is the body.” Yet much of her work alludes to the human figure without showing it. And crucially, when absent, the figure is made conspicuous by that absence. It’s in no one place in order to be everywhere.

As a rough but ready analogy - you know that scene from horror films, where someone pokes about in an attic full of weird old stuff, unsure whether something alive is hidden amongst it? In the films the cat is soon let out of the bag. Whereas this show is like rummaging endlessly about in that attic while remaining unknowing, and retaining all that enticing tension.

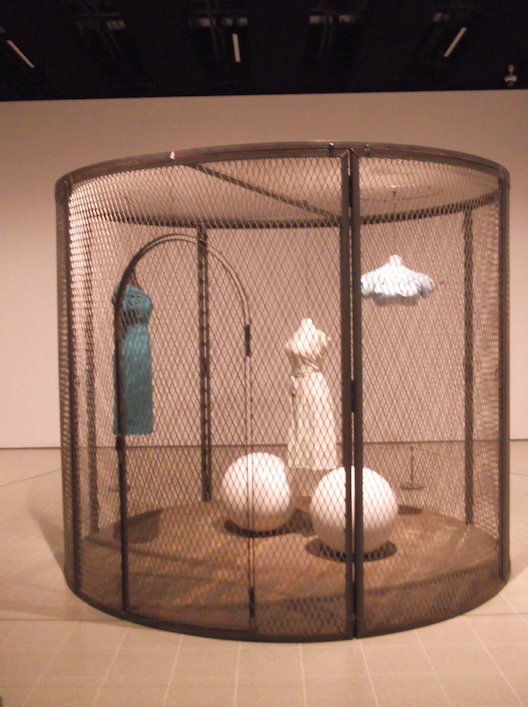

Let’s start off with the Pole pieces, where various elements are hung from a central pole (example above). They’re often items of clothing, as if arranged on a somewhat spectral radial clothes hanger. It recalls the commonly used Surrealist device, where clothes and mannequins are used to stand for the human figure. In one dated 1996 (all are untitled), a dress is sewn up and stuffed to resemble a mannequin.

The pole acts as a kind of equals sign, inviting us to compare the items around it. Which seems key. In general throughout the show its the large-scale assemblages which work best, where we have to somehow reconcile the often-disparate elements in our minds. (Even the piece from which the show took its title, a fabric book, is unmemorable.) So in another, also from 1996, a gnarled tree stump is combined with the clothing, with one truncated branch morphing into a mannequin arm.

Bourgeois called clothes a “second skin” and there’s a sense they’re to do with the extended self. (The way we formulate the terms “my foot” and “my shoe” so similarly.) But at the same time this expanded definition goes alongside a narrow one. Consciousness means that we’re aware we have a physical existence. Most living creatures don’t know this, precisely because that’s all they have. But consciousness can also lead us to the sense that physical existence goes on outside of ourselves, that our real self is elsewhere. And in practise our terminology becomes fuzzy, slipping between these two extremes. Sometimes our shoe is part of us, other times our foot isn’t.

At the same time she was producing Cells, installation environments enclosed by doors, walls or chain fencing, littered with objects. Many such as ’Cell VIII’ (1998, above) have narrow entry-ways. And we are, I suspect, intended to use them, to experience the work from inside, enveloped by it. (Unfortunately if unsurprisingly, they’ve been deemed off limits by a nervous gallery.)

Should we see these as rooms or head spaces? The point is they’re both. Earlier in her career, Bourgeois had produced a series of Femme Maisons, which were less anthropomorphised buildings than figures morphing into buildings.

Bourgeois’ career was long enough that she personally knew the Surrealists. Who she was simultaneously influenced by and took against, more-or-less for the reasons a women artist would. (She was a natural fit for the ‘Dreamers Awake’ show, on female responses to Surrealism.)

And, as mentioned, these phantom forms of the self are a Surrealist device. The Surrealists sought to undermine the notion of the essential self, which they saw as limiting. They developed a penchant for alter egos, and their works can often look like a self-portrait which has just been divided into its component parts, a cast of characters created to illustrate various aspects of the artist. All this is to the good.

But there’s times when this multiplicity of selves tries to do away with the central question just by sub-dividing it. What can look from outside as one person is in fact several selves cohabiting. We’re less like a classical bronze, solid and fixed, and more like a wardrobe, a collection of costumes. But the central question remains - what does it mean to have a self?

Bourgeois’ answer is that we become like a scrapbook of experiences we amass. These don’t build up like kit parts to create some core identity but perpetually interact. A little like the way we discovered atoms to not be a solid mass but a collection of particles in space, the self is little more than an optical illusion when seen from without. Elsewhere, a fabric head such as ’Pierre’ (1998, above) is held together by Frankenstein stitching, despite the cloth all being the same colour.

Along Came A Spider

“All very interesting”, you say, “but what about the spiders?” Bourgeois is famous for them, and one of the two variants of the exhibition poster is devoted to ’Spider (Cell)’ (1997, above), so let’s look at that next. A spider straddles a cell like a kind of double cage, and there is something deliciously menacing about those elongated, knotty legs.

Spiders do, in fact, have a body. At least they have head and abdomen segments. But we tend to conceive of them as a head sporting multiple limbs, an image we see in several of Bourgeois’ drawings. Part of our horrified reaction may be that we parse them as something we cannot parse. They appear to be physical beings but are unembodied, a defiance of what seems fundamental rules. So they come to represent utter otherness, as alien as anything on Earth can be. Hence their very existence can feel menacing.

But we also tend to parse them as feminine. Google has readymade answers to the questions “are there male spiders?” and “are house spiders female?” (Spoilers: “yes”, and “not always”.) Spider-Man aside, most spider characters in popular culture tend to be female. And this spider is shown with eggs, in the upper part of the cell. Her pose could be construed as protective of that cell. In which case, it’s being protected against us.

There’s also fragments of tapestry stretched along sections of the chain-link cage. And Bourgeois identifies spiders with her mother, who worked as a tapestry restorer. “The spider is a repairer”, she commented. And of course we need to bring together both these things. The ‘otherness’ of the spider remains part of the point. To Bourgeois, it’s the very thing which makes it something with which to identify.

The Needle And The Pin

On the subject of repairers, she further commented: “When I was growing up, all the women in my house were using needles. I’ve always had a fascination with the magic power of the needle. The needle is used to repair the damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness. It is never aggressive, it’s not a pin.”

Mostly it is remarkable to think she produced these works in decades most devote to watching UK Gold. However it is possible they represent an old person’s view of the world, a time when memory has more substance to you than substance has, when both your environs and mind are full of the detritus of earlier eras. Bourgeois said herself “I am a prisoner of my memories”, and she was perhaps caught in her own web.

In this way there’s a tension between whether her work is a repairing needle or a pin - in the sense of pinning something down, of documentation. Some critics claim to find her art pedagogically ‘feminist’ and therefore dismissible as one-dimensional. In fact it’s often highly ambiguous, and this is the axis on which that ambiguity plays out.

At times her art’s about the familiar Modernist frustration with the flesh, of our minds being stuck inside meat sacks which will slowly wear out on us. ’Lady In Waiting’ (2003, above) is another Cell, but of quite a different kind. It’s recursive, the small figure set inside a larger fabric chair, itself inside a doorless chamber. But also the figure is made of the same fabric as the chair. It isn’t just in the cell, but is of the cell - we are our own prison. Similarly the red legs (which must have been signed somewhere, but I couldn’t find it) have stigmata holes, as if bodily existence is inherently a form of crucifixion.

Perhaps significantly, its enclosed against us. (While elsewhere, vitrines are used as confining cells.) It’s sub-headed ’The View Of the World of the Jealous Wife’, as if a map of symbolic power, so perhaps owes us no other perspective. Yet where does that other perspective come in? Telling it like it is, that’s important. But in itself it’s insufficient.

The print ’Eternity’ (2009) is a clock face with a male and female torso set against every hour, one sporting an erection, the other already pregnant The pregnant belly is normally absent from Surrealist art, so fixated on male desire. Yet this also reads as essentialist, as if biology is all-defining to us. Every time is up-the-duff o’clock, with literally no way out of this endless round. In that sense it’s not so far from a work like Duchamp’s ’Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors’ (1923), which (as noted another time) involved “the reduction of sex to the mechanical.”

And ’Knife Figure’ (2002, above), where a chopping knife hangs poised over a pink mannequin, doesn’t look so different to some of Giacometti’s Surrealist sculptures, such as ’Man And Woman’ (1928/9) or the charmingly titled ’Woman with Her Throat Cut’ (1932). Does she intend as protest what they meant as simple description? Quite possibly. Does that make a difference? Yes. But not enough of one.

Whereas ’Femme’ (2005) is a block with ‘feminine’ parts attached, breasts and vagina. It seems linked to the notion of ‘femininity’ as a construct, an idea some have forced upon others.

Similarly, while the clothes could be her second skin, you could as easily see them as shed skins, relics of the past, the way a spider sheds old ill-fitting skins. The figure in ’Lady in Waiting’ has spools of thread going into her mouth, perhaps forming her, and spiders’ legs digging into her torso. Or is it the other way around, that she’s both exuding the thread and growing the legs? Could the cell be a womb-like space, in which it can grow?

This tension between pin and needle may be most acute in ’Repairers In the Sky’ (1999), where gashes in a metal plate are part-stitched together. This perhaps turns the magic of the needle in on itself. Whether we take these as eyes, mouths, vaginas or some combination of them all, does this turn ‘repair’ into a form of silencing, as erasure?

Overall, though ambiguity over this question runs right through her work, Bourgeois seems to fall more on one side. The existence of her art confirms that there can be such a thing as a woman artist, bringing a female perspective to things. The strange-but-true story that she saw little recognition till the Eighties may, at least in part, be due to this. But the content of her art, too often that merely looks back to before such a time.

Doors Marked Private

The items were sometimes foraged for, but often were personal effects, items of clothing she once wore, and similar. She said part of her fascination with the spider was that it made its web from its own body. And there’s no doubt that much of her work stemmed from her relationship with her father, which she regarded as emotionally abusive.

A door, used as a wall, on one of the cells is marked ‘Private’. And never let it be said we don’t know a metaphor when we run into one. What do we do when we reach this door? The standard answer is that we need the guidance of experts, who can unlock it for us, who can demonstrate their familiarity with her life by explaining where this particular object came from, and so on. And initially, this seam can seem a lucrative one to dig. We’re told, for example, to look out for when objects are in groups of five, representing the size of her family.

But these are breadcrumbs which will just get you lost in the wood. And we know this from those who’ve already followed them. Tracey Emin, a self-acknowledged Bourgeois fan who has even collaborated with her, shows us what the terminus of this trail is. Her ’My Bed’ (1998) offers no point of contact with the viewer. It shows us the messy, unmade bed where she had a depressive episode, but is silent on the episode itself. It’s like trying to figure out why a battle was fought, going only by marks left behind in a field. We who got there too late gape at the bed from the outside, remarking on the heightened sensitivities of the artist which we couldn’t possibly share.

Do these works tell us things about the artist? Of course they do, the artist made them! But the more challenging and more vital question is - do they say things to us? If they don’t then nothing is exchanged, and where there isn’t exchange there’s robbery. We shouldn’t look at Bourgeois’ work in that misdirected way, and we don’t need to.

Coming soon! You never know, there may be more visual arts reviews…

.JPG)

This, sadly, is a classic case of the kind of art that does nothing for me. But one sentence of your essay struck me: "The existence of her art confirms that there can be such a thing as a woman artist, bringing a female perspective to things."

ReplyDeleteThis is what I was getting at back when Jodie Whittaker was first announced and I was trying to figure out whether that was likely to be an interesting development, or merely stunt casting. Is there a way to be a female Doctor, bringing a female perspective to things while still recognisable being The Doctor?

Sadly, we never found out, as all we got was not-very-good David Tennant impressions. And with only a couple of Whittaker/Chibnall episodes left to go, it seems unlikely that that's going to change. I still can't figure out which of the two of them is most to blame.

(But Mike, does everything have to be about Doctor Who? No; but nearly everything is.)

It's art you need to experience, really. See it 'in person', walk around it. (But not, unfortunately, go in it.) Besides, some of those illo photos are by me and I'm not exactly a pro photographer.

DeleteAnyway, you know what I think about this. it's Chibnall who's to blame. He had one idea the whole three seasons. And it was a really bad idea.