”So I Turn Myself To Face Me…”

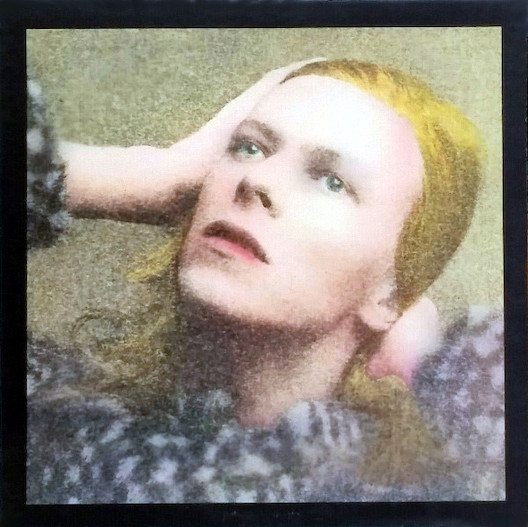

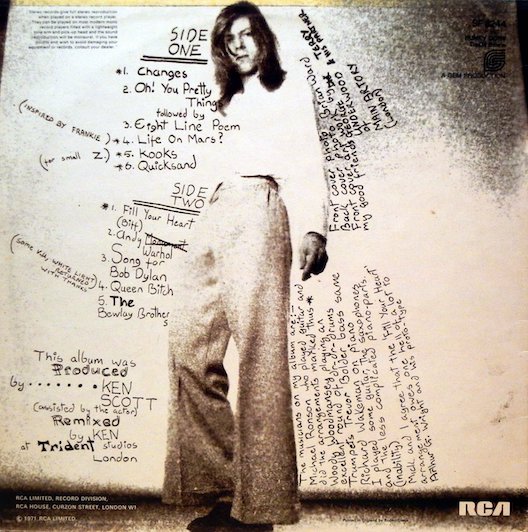

‘Hunky Dory’ (1971), David Bowie’s third album (depending how you count it) came between the mystic-folk-meets-primordial-heavy-rock of ‘The Man Who Sold The World’ and the snappy pop-rock of ‘Ziggy Stardust’. Each within a year of the next. But, bar odd tracks, and despite the Spiders From Mars being formed in all but name, it doesn’t sound like either. His voice is mostly accompanied by piano. Wrapped between a front close-up of a far-sighted Bowie and a handwritten back cover, it’s very much his singer-songwriter album.

Because of course those are all devices we associate with the personal voice, the raw unmediated truth, sung straight at us with no space for artifice. In ’Shock And Awe’ Simon Reynolds wrote “it resembled an existentialist Elton John”, and it often seems to be, in his own words…

“Written in pain, written in awe

“By a puzzled man who questioned

“What we are here for”

There’s even a direct tribute to the then-knighting King of singer-songwriters, Bob Dylan. Called, naturally enough, ‘Song For Bob Dylan’. Though it’s a mixture of tribute and barb, addressing him (as a disillusioned Lennon had) by his real name Zimmerman.

“We lost your train of thought

“Your paintings are all your own”

…was a none-too-subtle dig at his latest, underwhelming effort ’Self-Portrait’. In asking when we’d be getting the old Dylan back while knowing full well we weren’t, Bowie was clearly positioning himself as the great man’s successor. (Perhaps ironically, for an album which on release didn’t even chart.)

At this point Dylan’s run of late Sixties great electrified albums had only just happened. But Bowie skips over this creative peak, to go back almost a decade and focus on the righteous and dungareed spokesman for a generation with his Woody Guthrie cap and words of “truthful vengeance.”

Except Dylan performed those songs on guitar, the instrument of choice of protest singers, the one whose unadorned truth fascists were supposedly so allergic to. While Bowie’s on the piano. An instrument which can also signify ‘personal voice’, Joni Mitchell would swap between the two ambidextrously. But it’s as much associated with urbanity and verbal theatrics. (Perhaps because it’s less portable, or has a more dextrous sound.) And furthermore…

Audiences of the genre like singer-songwriters to be solo, or at least play the main instrument themselves, the way a painting is supposed to be all the artist’s own hand. They are even known to shout “Judas!” when they don’t think they’re getting this. But here even that piano is mostly provided by Rick Wakeman. (Who’d already played on ’Space Oddity’.) Bowie cheerfully conceded on that hand-written sleeve: “I played the less complicated piano parts (inability).”

And he plays into this, peppered the album with twists and turns on the theme. Even as he evokes “a voice like sand and glue”, he makes clear he’s as keen on greasepaint and glitter. “So I turn myself to face me”, could come from any singer-songwriter, making themselves their own inspiration. But Bowie quickly follows it with “but I’ve never caught a glimpse.”

’Quicksand’ refers to both Garbo and “the next Bardo”. Which could be, respectively, the wartime spy and Buddhist concept. Or perhaps the two glamorous actresses? People argue over which but… guys, really… twice in one song? Remember the sane/Seine pun from the previous album? He’s doing this deliberately, isn’t he?

‘Life on Mars’ is clearly Bowie’s zigzagged, idiosyncratic version of a protest song. While the two opening tracks, ’Changes’ and ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ would seem to be his take on the classic ‘Times They Are a-Changin’.’ (Perhaps the best-known early Dylan song after ‘Blowing in the Wind.’) Like their source they’re both ostensibly addressed disdainfully to an adult generation, telling them to get out our way (“don’t kid yourself they belong to you”), while of course they’re actually an anthem for marching youth.

Except Dylan’s song is full of quite Biblical imagery, floods and tribulations (“The line it is drawn/ the curse it is cast”). It opens with the proclamatory line “Come gather round people wherever you roam”, like a town cryer. While Bowie begins with “wake up you sleepy head”. His tone throughout is more intimate, conversational not confrontational. Even when he spies “a crack in the sky and a hand reaching down to me” he doesn’t dramatise, in fact he could sing in the same voice about the postman having come.

While Dylan was always writing accusatory “you” songs (usually pronounced “yeeeeeew!”), the first personal pronoun on this album is inevitably “I”. It’s clear enough that here its inner change, personal transformation, that counts. Bowie sings “I’m much too fast to take that test”. The streets aren’t made for political protest, they’re there to be treated as a catwalk. The secret to life is realise that this is all a show. And those children that you spit on try to change their world, they don’t just bring change, they represent it. Don’t just change one thing for another, be change, swap fixity for fluidity.

Simon Reynolds also wrote:

“Bowie came along at a time when the idea of revolution or alternative ways of living proposed in the Sixties began to fade. The big trade-off that ensured was the shunting of ‘revolution’ out of the social-political domain and into the commercial-aesthetic zone, as well as into the private life… Bowie is the emblem for this individualised, privatised form of revolution.”

And the man himself said, two years later: “The revolution has been fought on an entirely different plane to the plane that I thought it should be fought on… For instance, like capitalism can be all right.” (Another reason, should we need one, not to treat the Tomorrow People trope as somehow inherently radical.) He’d reject in song “that revolution stuff” of the Sixties - “what a drag, too many snags.”

While, interestingly, the chorus to ‘Song For Bob Dylan’ makes Sandy Glue’s adversary not Mr. Jones or some other fusty establishment figure, but “the same old painted lady/ From the brow of the superbrain.” Wait, what, who?

A clue might have come from the track straight before, another personal tribute, this time ‘Andy Warhol’. The words to which read something like a Glam manifesto:

“Dress my friends up just for show

“See them as they really are

“Put a peephole in my brain

“Two new pence to have a go

“Like to be a gallery

“Put you all inside my show”

For Warhol was more than anyone the self-proclaimed antithesis of the confessional school of creation - art was artifice, appearance, effect. He described himself as a “deeply superficial person”, and insisted “if you want to know all about Andy Warhol just look at the surface, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” For the press release, Bowie called him “a man of anti-message.”

Julian Cope later wrote ‘Christ vs. Warhol’, conveying how torn he felt between the rival pulls of pop immediacy and lasting grandeur. And Bowie at this point seems very Dylan vs. Warhol, split between really meanin’ it man and the desire to dress up and put on a show. An approach he arguably kept up over the rest of his career. He was the Seventies artist who was effectively employed to shut the door on the Sixties, yet at the same time never fully crossed that threshold himself.

And after all, how different were they really? Bowie’s already reminded us Sandy Glue was just a stage persona for Robert Zimmerman. And a corduroy cap and an acoustic guitar can be as much a pose as a blonde wig, as Dylan surely proved more than most. He said himself: “You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself.”

His “you” songs rarely stretched to “we”. That was more the era of the agitational late Sixties, perhaps reaching its succinct epitome in Jefferson Airplane’s “your enemy is we”. But it was a distinction most failed to spot, and his consequent failure to support that agitation mystified them. Bowie then positions himself to be Dylan’s successor, but with the “I” presented as a twist. His relationship to his fans was by the same mass media, but it was to be one-to-one, kids alone in their bedroom hearing a transformative track on the radio.

”The Start of the Coming Race”

And the man himself said, two years later: “The revolution has been fought on an entirely different plane to the plane that I thought it should be fought on… For instance, like capitalism can be all right.” (Another reason, should we need one, not to treat the Tomorrow People trope as somehow inherently radical.) He’d reject in song “that revolution stuff” of the Sixties - “what a drag, too many snags.”

While, interestingly, the chorus to ‘Song For Bob Dylan’ makes Sandy Glue’s adversary not Mr. Jones or some other fusty establishment figure, but “the same old painted lady/ From the brow of the superbrain.” Wait, what, who?

A clue might have come from the track straight before, another personal tribute, this time ‘Andy Warhol’. The words to which read something like a Glam manifesto:

“Dress my friends up just for show

“See them as they really are

“Put a peephole in my brain

“Two new pence to have a go

“Like to be a gallery

“Put you all inside my show”

For Warhol was more than anyone the self-proclaimed antithesis of the confessional school of creation - art was artifice, appearance, effect. He described himself as a “deeply superficial person”, and insisted “if you want to know all about Andy Warhol just look at the surface, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” For the press release, Bowie called him “a man of anti-message.”

Julian Cope later wrote ‘Christ vs. Warhol’, conveying how torn he felt between the rival pulls of pop immediacy and lasting grandeur. And Bowie at this point seems very Dylan vs. Warhol, split between really meanin’ it man and the desire to dress up and put on a show. An approach he arguably kept up over the rest of his career. He was the Seventies artist who was effectively employed to shut the door on the Sixties, yet at the same time never fully crossed that threshold himself.

And after all, how different were they really? Bowie’s already reminded us Sandy Glue was just a stage persona for Robert Zimmerman. And a corduroy cap and an acoustic guitar can be as much a pose as a blonde wig, as Dylan surely proved more than most. He said himself: “You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself.”

His “you” songs rarely stretched to “we”. That was more the era of the agitational late Sixties, perhaps reaching its succinct epitome in Jefferson Airplane’s “your enemy is we”. But it was a distinction most failed to spot, and his consequent failure to support that agitation mystified them. Bowie then positions himself to be Dylan’s successor, but with the “I” presented as a twist. His relationship to his fans was by the same mass media, but it was to be one-to-one, kids alone in their bedroom hearing a transformative track on the radio.

”The Start of the Coming Race”

Yet at the same time as all this Bowie ups the ante with the line that took us here - “better make way for the homo superior.” We’re “the start of a coming race”, not just different to their generation, but of another kind altogether. “The Earth is a bitch” (famously censored in the Peter Noon cover), suggests we’re leaving mere physical existence behind.

You could play compare and contrast to another great piano song, from the previous year - Neil Young’s ‘After the Gold Rush’. Which portrays the present as an impasse, a “burned out basement”, stuck between a Medievalist golden age and a silver science-fiction future, with spaceships to ferry to us to the stars. It’s eschatological, an SF retelling of the end-times, with aliens replacing angels to take the nice folk like us out of a place like this. (And remember “tall Venusians passing through” had appeared in Bowie’s earlier ‘Memories of a Free Festival’.)

Ever the early bird, Bowie was getting in ahead here. In the well-known tale he picked up the phrase “homo superior’ from meeting Roger Price in a TV studio. Yet, as we saw last time, Price’s ‘Tomorrow People’ series didn’t debut for another two years.

But this was another way he was still channelling the Sixties, for this cosmic mysticism had always been part of the hippie mentality. Once it had co-exited with fervent insurrectionism. But as the possibilities for radical social change faded, it was able to hog more and more of the stage. George Harrison had said in ’67 (quoted in Clinton Heylin’s ‘The Band You’ve Known For All These Years’):

“I read somewhere that the next… Messiah, he’ll come and he’ll just be too much… The majority of people are going to believe and they’ll be digging everything and he’ll come and say ‘Yeah, baby, that’s right’, and all those other people who are bastards, they’re gonna get something else.”

It’s a kind of inverted Calvinism, with the sober-minded short-haired businessman the damned and the indolent long-hairs the UFO-hopping elect. But it’s the same rigid division into saved and consigned. This is precisely what Nigel Kneale satirised with the Planet People in ‘Quatermass’.

Yet that “I” reasserts. The track which most aligns with ’The Tomorrow People’ is ’Pretty Things’, and that only comes as close as the plural “you”. ’Tomorrow People’s whole sell had been plugging into the we - you didn’t just join a gang, you became permanently telepathically linked. The teleological optimism of their premise was much more post-Sixties than Bowie. Questions like the role of violence in social change are literally not even questions for them, the answers seen as innate.

Bowie is much more personalised, more egotistical and at the same time more fractured. And it would be this less utopian take which would come to win the toss in dramatising the spirit of the often-contrapedal Seventies. Naming an album after a slang phrase for feeling good, that’s a surefire way of spelling out it won’t be very feelgood.

And significantly this album, which bombed on release, is not considered a classic. Bowie is often seen via his trailblazing influence on those who came after him. While ’Tomorrow People’ has become almost a byword for retro chic.

Which leads us to…

”If I don’t explain what you ought to know…”

’Quicksand’ is the album track of the album, not the one you went to it for but the one that keeps you there. Somewhat self-disparagingly, Bowie said he wrote it while still pretending he understood Nietzsche. But it’s more about not understanding Nietzsche, having a head full of half-digested notions of the ubermensch, stewing with some semi-masticated Cowley and chewed Buddhism. There’s a long list of characters, but they all seem to exist only in Bowie’s head. He described it as an “epic of confusion”, representing a “cacophony of thought”.

It reminds me most of student life, picking up one author and being swayed almost just by touching the cover, then trying another and being immediately converted, transferring your allegiances so often you get giddy. It’s the perspective of a young man, his voracious but magpie reading eye always bigger than his word-digesting brain, so constantly getting sucker-punched by erudition. Ultimately, it’s about having a reading hangover. The song we all struggled so hard to understand in our teenage bedrooms is ultimately about struggling so hard to understand. The war imagery, so pored over when Bowie attracted his own flock of magpie readers, stems from there.

But the album’s magic happens when these three themes intersect. Bowie was at this point coming up with songs at a rate of knots, so was free to choose what went with what for each album. (Many Ziggy songs were at this point already written, but saved till later.)

This doesn’t make it coherent, just cohesive. If he sang of being “torn between the light and dark”, that doesn’t map precisely to Dylan vs. Warhol. But 'Quicksand’ still internalises the conflict staged elsewhere, relocates Young’s “burned-out basement” inside his brain. While singing of a “crack in the sky”, he was only a few years from drawing a dividing line down his own face and in-so-doing creating the most potent self-image of his career. He’s not hoping the rest of the elect pick him for the team, he’s quizzing himself what his nature might turn out to be.

“I'm not a prophet or a stone-age man

“Just a mortal with the potential of a superman

“I’m living on”

And this creeps into other songs. ‘Pretty Things’ is more complex than the glam anthem it might appear, however proto-Ziggy that rousing chorus. Though thought to be written before his first child was born, “wake up you sleepy head” suggests that’s who its addressed to. The man who shortly would become a transexual alien saviour is here a father; at a time of great generational conflict he’s trapped between the sides. “Look at your children… Don’t kid yourself they belong to you” could be addressed as much to himself as some squaresville grown-up.

When that sky cracks and the hand points down to him, there’s no real telling which side of the divide he’ll be falling on. Let’s remember that ’Cygnet Committee’ two albums back, ostensibly a state-of-the-Sixties song is effectively about a parent/child relationship in which Bowie also gave himself the parent role.

Faulkner famously wrote “the only thing worth writing about is the human heart in conflict with itself”. Which is ultimately where ‘Hunky Dory’ is at, the befuddled mortal and the would-be superman in symbiotic struggle.

I have a weird relationship with Bowie. I was first aware of him in the early 80s, when he was tarred by suspicion by the mere fact that he had successful singles in the same era as Duran Duran and Culture Club at the time I was listening to Deep Purple and Pink Floyd. He was the kind of music my sister listened to. I long ago realised how silly this is, and set out to like Bowie, starting with Ziggy Stardust. But somehow that album has just never landed with me. So here I am left, loving just two songs (Life on Mars and Wild Is The Wind), and wondering when the lightning will strike. Given my tendency to appreciate the singer-songwriter idiom, maybe Hunky Dory is the place to make another start.

ReplyDeleteHe didn't write 'Wild Is the Wind', so that may be just one song!

DeleteWithout resorting to the "always reinventing himself" cliche, I don't think it's terribly important where you start with Bowie. If you already like 'Life On Mars', then 'Hunky Dory' is probably a good bet.

The only two I'd say to avoid, at least initially, are the two contenders for the first album. The first first album, if you follow, is a bit of a Sixties timepiece and he later effectively repudiated it. The second has high points but is both uneven and inconsistent, which makes it a strange listen.

And much of the Eighties stuff is production line, it's true. He later said he'd been consigned to "a netherworld of commercial acceptance".

Wasn't 'Another Brick In the Wall' the same era as Duran Duran and Culture Club?

Thanks, Gavin, Hunky Dory it shall be!

ReplyDeleteYou make a fair point about Another Brick in the Wall. I suppose what happened there is that I approach Pink Floyd by such a different route that I hardly registered that it was by the same band (although I knew it as a fact).

I keep wondering as well whether Tears for Fears might be worth a look, despite their sin of 80s popular success.

Brief reply, Nooooooooooo! Do not be distracted by the cover of 'Mad World'. (Though bizarrely, latter-day Talk Talk was often pretty good.)

Delete