In this first part of our new series Mutants Are Our Future, we hold up the first issues of ‘Uncanny X-Men’ and ‘The Fantastic Four’, the better to compare monsters to mutants

”It Ain’t Human!”

Mutants, when did they change? When did they stop being scary distortions of human form, who hung about in forbidden zones with backwards Rs on their signs and especially hankered after half-dressed blondes? In the 1955 film ’This Island Earth’, for example, ‘Mutant’ is really just science fiction for monster. So when did these monsters switch to become the next step in human evolution? Which turned out to be developing super-powers while wearing flashy latex.

A significant part of that shift was Sixties Marvel comics. In fact it started with one title - ‘The Uncanny X-Men’, debuting in 1963. I often find people insisting that this was the point where superhero comics hit on a potent metaphor for racism. But as we’ll see the reverse is closer to the truth.

’X-Men’ 1 came with the cover catchphrase “in the sensational Fantastic Four style”. It was the second Marvel super-team to be cut from whole cloth (‘The Avengers’ having been assembled from existing characters) and unsurprisingly cribbed from its 1961 predecessor. (In at least one account of events, publisher Martin Goodman noted the FF was selling and told his charges “do another one”.)

Reed Richards is essentially split into two characters, Professor X and Cyclops, the brainiac boss and the sober-minded field leader. While the feuding horseplay between Ben Grimm and the Johnny Storm is transferred to Hank McCoy and Bobby Drake. Bobby, like Johnny, is the youngest team member. The fire-powered one is replaced with Iceman, like that reversal of elements might be enough to conceal the copy. In a similar vein, McCoy’s Beast would later name-defyingly spout thesauruses in his speech balloons. But they hadn’t come up with that yet, so here he even sounds like the Thing. (His first line is “leggo my arm, you blasted walking icicle.”)

And the books start out structurally similar. The Hulk begins with Bruce Banner, and we go on see how he became big and green. Spider-Man starts with Peter Parker in High School, Thor with Dr. Donald Blake and so on. But with both the FF and the X-Men we’re thrown straight into the action. It’s as if we just walked up to Xavier’s school window and peeped in. Characters and concepts don’t get introduced like on your first day at work, they just appear and leave you to catch up.

It’s a more common way to introduce villains than heroes, for them to rear up at us for shock value. In fact it’s just the way Magneto gets introduced, later in this same issue.

Though the reason for this probably differed. The FF were the first Marvel book, with no norms established, so trying to draw in the reader with a baiting opening was a virtue found in a necessity. And the X-Men couldn’t start with their origins because… well, they didn’t have any. As Marvel’s first mutants, their super-powers just manifested. (Lee later confessed he’d chiefly come up with the notion so he didn’t need to concoct a new origin story each time.)

But these similarities just shows up deeper differences between them. We see the FF become the Fantastic Four separately, each individually set against the great American public. We see the X-Men assemble in their school, and go through their motions. In short the first time we see the FF the thing that’s stressed is their effect upon humans. And with the X-Men it’s their team bond. Like the FF the X-Men are an honorary family. Yet as we get to witness, the FF knew each other before the ill-fated rocket expedition. The X-Men come together precisely because of their mutant status.

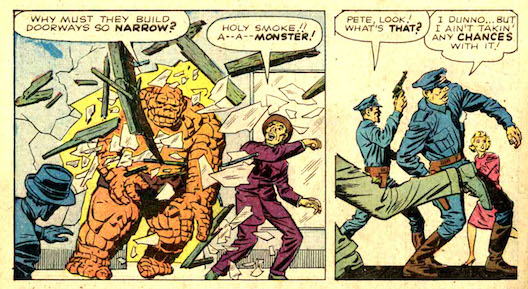

And the first public reaction to the FF is not the admiring public watching Superman perform a fly-by. Its horror and fear, the reaction to monsters. Let’s focus on the Thing who, alongside the Hulk, was the most monstrous Marvel hero. As he smashes his way out of a shop doorway (leaving you wondering how he ever got in), someone cries “Holy smoke!! A - a - monster!” and a cop starts shooting. Later someone adds “It ain’t human!”

Though it’s hard to think back to this now, for the original readership this was their first sight of the Thing. Their reactions would have been much the same as the characters in the story. Not “here’s our hero”, but “a - a - a monster!”

Superheroes might transform their appearance, like Captain Marvel. Essentially Johnny Storm does this with his “flame on!” But Ben Grimm is stuck as this feared monster. Later stories featured Reed’s perpetual attempts to cure him, which (spoilers) always prove short-lived.

In fact the one person the Thing seems to have something in common with here is the villain, the Mole Man. Whose lumpen looks have led to him being shunned by society, hiding out underground with other monsters for companions, like it’s the world’s basement. “Even this loneliness”, he concludes, “is better than the cruelty of my fellow men.” The monsters he (somehow) commands are probably best understood as ‘Forbidden Planet’-style projections of his rage. The story ends with his death (no, honest) and Reed concluding “there was no place for him in our world.” Takes one to know one, you can’t help thinking.

Both comic books were created by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee. (Let’s not get into who did what right now.) Who were but two of many comic artists of their day to be Jewish. Lee was younger but both had been through the Thirties and Forties, so would inevitably have come across a great deal of anti-semitic propaganda - where people like you were effectively monsterised. Just consider that a sec. You’re not just thinking “that’s offensive”. You’re thinking “this is how others see me.”

Then, add the Civil Rights era. It’s true that the racist image of ‘The Jew’ was different, possibly even opposite, to that of ‘The Black’. Associated with usury, ‘The Jew’ is not a real man who lives by honest labour. Kafka’s phrase "damned loathsome thing” perhaps sums this up. Whereas, stemming from slavery and still associated with heavy labour, the problem with ‘The Black’ was that he was *too* manly. He was required for his supposed size and strength, but feared for it in equal measure. But direct experience of racism naturally lent them to sympathise with other such victims.

Next, happenstance. This monsterisation went alongside an industry predilection for monster stories, not least at Marvel. (Thing and Hulk were names both already used for monster stories before their now-better-known versions.) So, feared and shunned for their size and strength, the Thing and Hulk become associated with the ‘super-predator’ fears of anti-black racism.

In some ways between the social groups of white and black, they are able to articulate the white man’s fear of becoming, and being treated as, black. It’s similar to John Howard Griffin’s 1961 book ‘Black like Me’, a white journalist’s account of travelling through the segregated South as black. (Which was filmed in '64, and generated so much hostility he later moved his family to Mexico.) Interestingly this device echoes the earlier film ‘Gentleman’s Agreement’ (1947), where Gregory Peck plays a white journalist who poses as Jewish.

It’s an incomplete metaphor, of course. The most widespread and pernicious form of racism, structural racism, is bypassed to (yet again) individualise the problem. And our modern sensibilities want to ask why, instead of getting a white journalist to essentially black up, to know what being black or Jewish feels like - why not just get someone to tell us who’s… you know… black or Jewish?

But it captures something of how racism feels, from creators who had themselves experienced racism. And it does it juxtapositionally - it’s about having monsterisation thrust upon you.

(And as times went on even white-bread DC comics got in on the act. In 1970, issue 106 of ‘Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane’ was titled ‘I am Curious (Black)', where she declares “it’s important that I live the next 24 hours as a black woman.”)

”Got to Make Way”

So, how do mutants differ? In the first X-Men film, released in 2000, Professor X spells out the concept:

“Mutation, it is the key to our evolution. It is how we have evolved from a single-celled organism into the dominant species on the planet. This process is slow, normally taking thousands and thousands of years. But every few hundred millennia, evolution leaps forward.”

Though back in ’X-Men’ 1, Lee has still not entirely given up on his belief in the transformative properties of radiation. Here the great Professor says “I was born of parents who had worked on the first A bomb project…. I am a mutant… possibly the first.” Lee had previously loaded the Marvel universe with the stuff, springing up like whack-a-mole, always a flying canister or glowing spider for the unfortunate to run into. He now declares it all-pervasive. Functionally, of course, it’s still magic pixie dust mislabelled as science. Yet that upping of the ante makes a difference.

In ’The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction’, Paul A Carter points out “the nuclear bombs of 1945 inspired swarms of stories about radiation-induced human mutation, taking place no longer in race isolation... but in populations large enough to constitute substantial colonies. Authors could address themselves to the question of how such societies might function internally.”

And we see a version of that here. The Fantastic Four had stumbled into their super-powers, but by boarding the space rocket they had already chosen adventure. The X-Men, conversely, were simply born into changing times. Innate outsiders, they must build their own world. (Though the outsider schtick was at this point unevenly applied. In the second issue, the Angel’s held up from a mission by a mob of adoring girl fans, as if there was X-Mania afoot.)

Except there’s more… The formula is - radiation catalyses mutation, which in turn catalyses evolution. Evolutionary biologists are most likely sighing loudly at this point. But what concerns us here is the fictional applications. Popular culture tends to assume that evolution is teleological, that it’s essentially creation but without the God bit. Perhaps working more slowly but still towards some end-goal. Mutation then is evolution freed to speed up.

’X-Men’ 1 uses the term ‘homo superior’ once only. But that may have been enough to let the cat out of the bag. Because it goes on to be proclaimed quite openly as the trope advances, and particularly in popular song. There was Bowies ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ (1971):

“Homo sapiens have outgrown their use

“Let me make it plain

“You gotta make way for the homo superior.”

Radio Birdman then upped the ante still further with ‘New Race’ (1977):

“There’s gonna be a new race

“Kids are gonna start it up

“We’re all gonna mutate

“Kids are saying yeah hup”

(Everyone got that? “Yeah hup.”)

And what does this do but confirm the obsession of the most hardline racist - the ‘great replacement’ theory? Why are other people black or Jewish? Clearly to conspire against you and me!

Which is what makes mutation the single worst metaphor for racism. In racist conspiracy theories Jewish people are already in essence super-villains - masterful, elaborate schemers, secretly in control of everything. And not just more folk holding down regular jobs, like they actually are. Whether heroes or villains, mutants… well, they quite clearly are different to you and me. The X-Men’s Magneto was retconned as Jewish. Out of the Jewish people I know, not many can bend metal with their mind…

(Perhaps most bizarrely, as the series progressed Professor X’s mind control powers were more and more employed. Though more than once he’s wheeled out as a deus ex machina device, mostly they’re used to re-establish plot stasis; at each issue’s end he’ll wipe the memories of those who’ve learnt of the X-Men’s existence. Which seems to skate remarkably close to anti-semitic tropes about the seemingly physically weak who manipulate their world, conceits about the “Jewish-controlled media” and all the rest.)

But what’s a lie about race is a self-evident truth about age. One generation does replace another. And what was the other great sociological event of the Sixties, alongside the Bomb and Civil Rights, but the generation gap? Which proved perhaps more rupturing. Adults aren’t just party poopers, telling you you can’t use the car cause you didn’t work late. Now, in Dylan’s words, “Your old road is rapidly agin’/ Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend a hand.” When Prof X. says “there are many mutants walking the earth… and more are born each year!” it presages the later hippie saying “there’s more of us being born and more of them dying.”

Most people work out sooner rather than later that ‘breaking out’, as it’s called on the (upcoming) ‘Tomorrow People’, where your powers suddenly manifest unexpected and inexplicable transformation, is a metaphor for puberty. And like mutation puberty feels like evolution speeded up. Physical changes such as growth seem to happen frustratingly slowly to the young child. Then with puberty it’s like you were suddenly zapped.

(Though it’s also possible to overstate the significance of this. I certainly bought into the concept of the Tomorrow People, to the point where I’d keep watching an average-at-best show, long before puberty. And the most puberty-related character of classic Marvel was not a mutant but Spider-Man, again often beloved by young children.)

”The Day of the Mutants”

The opening line, “in the main study of an exclusive private school”, makes the whole thing seem about as cosy as Harry Potter going to Hogwarts. The Angel seems to be identified as the posh one to stop us noticing they’re all the posh one. Yet noticeably, at this stage these teens are very much teens. They’re regular kids who happen to have powers, indulging in horseplay and (not the issue’s most edifying moment) going ga-ga over Marvel Girl’s arrival.

The cerebral nerds and band of outlaws comes later. (And Kirby in particular, having a rough blue-collar upbringing on the Lower East Side, would have had little inclination to identify with them.) Perhaps it’s just hard to unsee. But it still seems inexorable. This is a path that leads to ‘the geeks will inherit the Earth’. As Richard Reynolds has said: “Much of the appeal and draw of the mutants that comprise the X-Men has to do with feeling like an outcast while simultaneously feeling like part of a family.”

Many monster stories throw in a switch by showing us a horrific creature then asking us to identify with it. Mutant stories presuppose that identification. Because we’re primed to see ourselves as the special one. First, to the racist mind, whiteness is considered a form of evolution in itself. Blackness is associated with Africa, with primitivism, whiteness which progress. Science fiction often fetishises whiteness as an aesthetic. To this mentality, whiteness is already a mutation, a signifier of improvement.

Comic fans, commonly white and from comfortable backgrounds, can identify with this more than most. And inasmuch as it works as a form of anti-racism, it’s not one where white folks renege on their privilege. It’s one where we assume we will naturally use our special powers for the greater good, such is our benevolence. Black folks are still held to be not as smart as us but that’s why we should take it on ourselves to look after them anyway. It’s a means by which we can feel simultaneously superior and virtuous.

Perhaps because they’re neither teens nor nerds, Kirby and Lee seem to see this problem. And their solution is to acknowledge it by externalising it. Enter the X-Men’s foe, Magneto, exemplifier of “the evil mutants”. “The human race no longer deserves dominion over the planet earth!” he monologues. “The day of the mutants is upon us!” Unlike the Mole Man, nothing happens within the first story to contextualise his stance or make it even semi-sympathetic. He’s just like that, in the same way the X-Men are just not like that.

The FF’s first reaction to their powers is to get into an acrimonious fight, then place their hands together in a pledge. The X-Men fight too, but in what’s emphasised to be no more than juvenile horseplay. All the negative stuff gets pushed onto Magneto.

But a side effect of this mechanism is to marginalise the regular humans. We’re told the reason for the secrecy round the school is their fear and distrust. But unlike FF 1 we never witness any of this. The only humans we encounter are, briefly, the US Army. Who quickly give this strange-looking team their blessing to take on Magneto.

Furthermore, unlike the Thing all of the X-Men can pass for human when they need to. Even his nearest double, the Beast. The ability of humans, already restricted in scope to fearing and shunning you, gets diminished further. Even the American army is the equivalent of the heroine in a Victorian melodrama, there to be rescued.

And if villains are normally the return of the repressed, the Mole Man was our fault. We were the ones who sent him into the exile from which he burst back out from, monsters in tow. Whereas in this closed loop Magneto exists solely to be the antithesis of their family group, the kid who plays nasty because he’s so used to playing alone. The relationship is quite close to International Rescue versus the Hood in ’Thunderbirds’. All you’d really need for a perfect match would be Magneto engineering the crisis to draw the X-Men out.

Of course you can’t always tell the flower by the roots. The FF had, after all, already changed quite considerably in the intervening couple of years before the X-Men’s first appearance. (Let alone later.) Read the two first issues together and you get such strange sights as the Thing not yet talking like the Thing, while the Beast does talk like the Thing! At one point Magneto skulkingly hides from the X-Men, hardly how he came to be.

Nevertheless, as soon as coined mutants were everywhere. With the aid of retconning. “I??”, asked the SubMariner in issue 6. “A mutant?? Why has that thought never occurred to me before?” Possibly for the same reason it’s never occurred to me. Because I’m not one.

But the clincher comes in issue 3, where the Blob first wobbles in. He’s told he’s a mutant by the X-Men, as they think this will lead him to join them. Instead he uses his new-found powers to fight them. Except… well, it’s not his powers that are new. He’s already using them in his circus act. It’s knowing the word, having the label to stick on himself, which makes the difference. “For years I thought I was just an extra-strong freak! But I found out what I really am! I’m a mutant! Understand? I’m one of homo-superior! And that means I’ll run this show from now on!” To which the only solution is Professor X getting him to forget the word again.

And so us regular folk are forever sidelined, dismissed by the Blob as “rubes”. Except of course we don’t see the humans as us at all. We see them as them, the semi-hysterical rabble in the street scenes, the nameless extras in our lives, but not our special li’l selves.

The X-Men’s introduction emphasises their otherness. But from there, first our interest, then our identification gravitates to the mutants. The fundamental premise, that this stuff is written not for the common herd but special people like you and me, may be less upfront but is there from the start. Issue 15 ended with the payoff “even if you’re not a mutant you mustn’t miss” the next instalment.

Coming Soon! Even if you’re not a mutant you mustn’t miss the next instalment, our comparison of the X-Men to the Tomorrow People…

Interesting. I have something presently on the back burner along these lines and agree that the mutant soap as metaphor for racism deal seems a little overstated / convenient. I'm presently wrestling with our guys as an outgrowth (albeit indirectly) of the Gernsbackian (etc.) fascination with supermen (see A.E. van Vogt's Slan and others), itself wrestling with the still not entirely digested realisation of biology being subject to change, as distinct from determined by the man upstairs, with which everyone from Shelley to Stoker to H.G. Wells wa preoccupied to a greater or lesser extent. Thumping good read as ever, and good luck with the Tomorrow People. Rather you than me.

ReplyDeleteThanks! Not only is the mutant thing a poor metaphor for racism, the irony is they threw away a more workable one - the monster - to get to it.

DeleteJust what makes the TP something you say "good luck with" about, that's something I'll pick up on.

I did think, very tentatively, of doing a successor series about the mutant trope in Yer Proper Books. Went so far as buying a copy of 'Slan', after near reading any Van Vogt before, but unstarted as yet.

"And our modern sensibilities want to ask why, instead of getting a white journalist to essentially black up, to know what being black or Jewish feels like - why not just get someone to tell us who’s… you know… black or Jewish?"

ReplyDeleteNot having seen the film, perhaps I shouldn't comment.

But this is the Internet, so you know I'm going to.

To me, this seems like obviously the right move. The real power of this film is surely the difference between how the same man is treated when he has white and black skin.

"The formula is - radiation catalyses mutation, which in turn catalyses evolution. Evolutionary biologists are most likely sighing loudly at this point."

ReplyDeleteEvolutionary biologist here. Actually, no, this is pretty much spot on!

Well I've never seen the film either, and it didn't stop me. (NB Have seen 'Gentleman's Agreement', not 'Black like Me'.) Couldn't you just ask a black and a white person, then note the differences?

ReplyDeleteWait, i have opposable thumbs because of radiation? Stan Lee is righter than i thought!

Here's a day-job question - is there a term for the notion that evolution always inherently accumulates advantages? 'Teleological' isn't quite right, as it implies working towards an end point.

I have been promising to think about The Tomorrow People as well. It’s not very good.

ReplyDeleteI am in a profound state of non-disagreement.

Delete"Couldn't you just ask a black and a white person, then note the differences?"

ReplyDeleteYou could. But you surely see that this is much less rhetorically forceful. The point the film makes is that the same man is treated differently depending on whether he is perceived as black or white. There is no wiggle room for someone watching the film to say "Well, of course the white man is treated better than the black man, it's because he's better educated, or had a better social background, or [some other reason]". But with the film as it stands, no such argument can be made.

"Here's a day-job question - is there a term for the notion that evolution always inherently accumulates advantages? 'Teleological' isn't quite right, as it implies working towards an end point."

Hmm. You'd think there would be a term for this, but I can't think of one -- unless you count "wishful thinking". It's essentially the same kind of assumption that people are operating under when they assume that each successive Covid variant will be less severe than the last -- something that there is no scientific reason to think will be the case.

This is a strange comment. Racism works precisely by denying certain social groups access to decent education and so on, then acting as if that was somehow their own fault. The cause of racism is not skin pigmentation. Skin pigmentation is just a hand hook to hang it on.

ReplyDeleteAnd even that isn't always necessary. In 'Gentleman's Agreement' the lead character passes himself off as Jewish simply by stating he's Jewish. And the social assumption is that no-one would say that unless it was true.

It's a bit hard to tell the order, but I fear the notion Covid variants would get progressively less severe was a popular one, which Bojo the Clown then used to base his completely dishonest policies on. I've found that, when I tell people that's not the case, some express surprise but many simply tune me out.