- Courtney Love

”You Showed Me Just What I Could Do”

Polly Jean Harvey’s fifth album, ’Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea’ (2000) features her singing “is this love, is this love that I’m feeling?” like trying to hit on a name for some unfamiliar taste. It was described by Caroline Sullivan as her “wild-love-in-New York record… that bubble[s] over with adoration for a significant other, with the city as its backdrop.”

All of which made for a contrast to the earlier darker, more bluesy mood, particularly on her first two albums. Back then weightier tracks seemed to thicken the air around them, as characters entangled themselves in their own follies and desires. Tracks were called things like ’Water, ‘Hair’, ‘Legs’, ‘Snake’ and ’Man-Size’. Imagery was mostly bodily, nature-based or elemental. (’Kamikaze’ is perhaps the only number here which kept up the old ways. Listen for example to her high-register voice on the chorus.) Yet she broke up her original trio to embark on exploits new.

We’ve grown so used to love songs we tend to tune out the words as soon as we glean that’s what’s going on. They’re like politicians promising prosperity. Yet despite all the dead weight of overspent cliches, sometimes a record comes along which genuinely seems to bottle the feeling, the euphoria, the sense of daily life transformed into something thrilling. To cite the old Situationist saying: “Being in love means really wanting to live in a different world.”

There’s a tradition more often found in Latin arts (for example in the films ’Les Amants Dans Pont Neuf’ (1991) and ’Betty Blue’) (1986) where the lovers are counterposed to society. They just want to be together but the demands, possibly the very presence, of others inevitably insinuates its way between them. In this tradition the lovers’ desire to be together is tantamount to their fusing into one.

“When we walked through

“Little Italy

“I saw my reflection

“Come right off your face”

And isn’t the city the perfect backdrop to a love affair? A burst of endless energy passing around and through you, streets to discover just as you discover each other.

Remember how being out on the town would be demonstrated by old films? With a whirling montage of bright neon lights, careering traffic, dancing girls and spouting champagne? Tracks such as ’Good Fortune’ feel like those sequences looked, erupting in a euphoric rush. And rock music itself seems to belong with the city, as much as it does with electricity.

So the album’s shot through with parallels between big and small, between the vast and the immediate. “Do you remember the first kiss?/ Stars shooting across the sky.”

And Harvey pointedly sings “from England to America”. British artists have long had a tradition of the American album, the hit-and-rush of being plunged into the States on their first tour. Except it meant something simultaneously narrower and broader than that suggests. The American album was often really the New York album. And sure enough all those landmarks show up here, Brooklyn, Little Italy, the Empire State Building.

But at the same time it was the city album, the reaction to metropolitan life. Because even if they existed elsewhere New York was still the ur-city, the city of cities. (For later generations this may well become somewhere in China.) And notably this album titles itself not after New York but the more archetypal “the City.” (Harvey herself said that many songs were written during a long stay in New York, but it shouldn’t be seen as her New York album.)

Like rock music cities can feel liberating. You can throw off the weight of custom, of social expectation, to finally become yourself. Partly, their mass nature offers anonymity. But it’s a feeling which gets fused with the geography of a city, boulevards to stride along, rooftops to scale and look down from. That’s a feeling caught in art and literature aplenty. So the open streets of the city enables the affair, letting the lovers run down them past a sea of strangers. (“Threw my bad fortune/ Off the top of/ A tall building.”) It’s cities which have freeways, after all.

”Just Give Me Something I Can Believe”

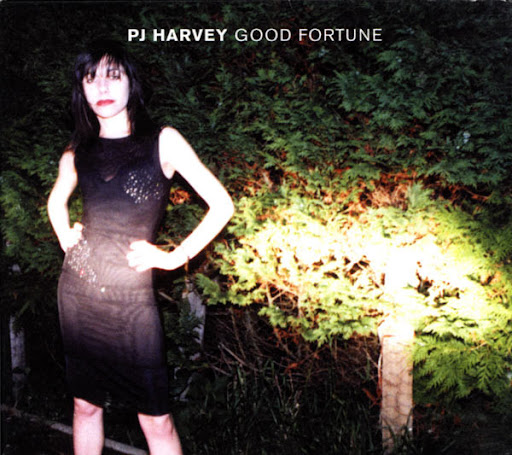

Exhilarating, but perhaps not sufficient. For an album with so many love songs, only one’s a duet. (‘The Place We’re In’.) And both the album cover and video for ‘Good Fortune’ show her amid the whirlygig of a night out on the town, but adventuring alone.

Exhilarating, but perhaps not sufficient. For an album with so many love songs, only one’s a duet. (‘The Place We’re In’.) And both the album cover and video for ‘Good Fortune’ show her amid the whirlygig of a night out on the town, but adventuring alone.

Or maybe not? What if in that opening quote Sullivan had it right, but wrongside-up? What if the city’s not background but foreground?

You sometimes entertain theories about art not because you want them to be right, for the internet to unite in agreement with you, but because you just want them to work for you - and only in that moment. Even terms like ‘headcannon’ are too strong to describe this, for you need to be free to dump your own theory as soon as it stops working for you, and move on to entertain something else - even if it formally contradicts. It’s not about them being right, but useful.

It’s like placing a filter over a photo. It allows you to see that photo in a certain way, it brings out some elements and diminishes others. And you can take it away again when you’re finished with it.

And as one such theory, what if the love affair doesn’t just take place within the City but with it? The never-named lover is a personalisation of the place, its liberating force jolting through you like the sensation of being in love. ’You Said Something’ keeps coming back to that “something” you said (without ever saying it, naturally enough). What if it isn’t said before that Manhattan view but by it - by the flashing lights, the colours and the five bridges. All of that stretching vista seen as a message just for you. Me-into-you morphs into me-into-City.

Harvey has been dismissive of the notion her music should be taken as displaced autobiography, and understandably so. Too many confuse the impetus of a song with its meaning. But it’s perhaps notable that she was brought up in the scarcely-more-rural location of a Dorset farmhouse. (While I may love the album so much having grown up in a small town. As a child my intention was to move to America, and change my name to something more befitting this new land. At the time Fred seemed a good choice. And naturally by America I meant New York.)

”When You Got Lost Into the City”

On release, most concentrated on the album’s bright and striking new tone. But if this is about a love story with the city its a torrid and tempestuous affair, not one solely spent watching sunsets. Just like getting lost in the city, it has another face. Which is, to quote another lyric, “sharp as knives”.

It opens, after all with declamatory guitar and the lines “Look out ahead/ See danger come/ I want a pistol/ I want a gun”. And more knives and guns ensue than are found in your normal love story. Because the overpowering city cannot but cast its shadow over you, dominating you and rendering you anonymous. From the Bible via Brecht and punk (all three lyrical or musical influences) comes the longstanding tradition of the City as Babylon, the centre of all that’s corrupt and oppressive. And this shadow spreads over numbers like (the near-Brechtian titled) ’The Whores Hustle and the Hustlers Whore’. (“Too many people out of love”).

The tracks here often sound just as energised but by a different kind of energy, one not bestowed upon you but generated by necessity. The link’s reversed, the City doesn’t enable you but comes down upon you. It becomes a battlefield, its “universal laws” set against your “inner charm”. You’re in a constant state of agitation, if not outright war, just to keep hold of your own self. (“This world’s crazy/ Give me the gun”). The line “Little people at the amusement park” always reminds me of Harry Lime’s infamous cuckoo clock speech in ’The Third Man’, delivered looking down at human dots from a Ferris wheel.

In fact it comes to feel so Babylonian it’s inherently apocalyptic, as if set somewhere so mighty the only possible next step will be a fall. Though written long before the terrorist attacks on New York on September 11th, it now seems almost impossible not to hear the album in that context.

"Sometimes it rains so hard…

“And in my heart

“Feels like the end of the world”

But, and should there be any regular readers they’ll doubtless be ahead of me here, the magic happens when these misfitting pieces are put together regardless. There’s no absolute division between the themes, more the feeling that as two sides of the same coin one bleeds into the other. The album starts with ’Big Exit’, running into ’Good Fortune’. The in-your-eyes lovers morph before your eyes into the folk staple of the outlaw couple, living not just outside of but against society.

Because when seen from a distance, the City isn’t just where the good stuff happens, or even the bad stuff. It’s where the stuff happens, while the small-town backwater you inhabit is a featureless, event-free purgatory.

”One Day There’ll be a Place For Us”

And there’s one other aspect to the album, which I suspect is more (if not entirely) personal to me…

Part and parcel of my leaving that afore-mentioned small town was my ability to enmesh myself in political activism. Which I was soon pursuing with the fervour of a love affair; the exhilarating feeling of being transformed and being able to transform, the desire to be everywhere at once, the belief you could punch your way out of consensus reality into a better one by force of will alone. You told yourself everything was heading towards a mighty conflagration, during which the future would be hammered out.

It was heady stuff, and inevitably it made you headstrong. It came with a tendency to fetishise conflict beyond any context, and a romanticisation of crime as some inherently Robin Hood affair. We indulged all that, in the words of the song, “until nothing was enough/ Until my middle name was excess.”

This being Britain, none of us actually had guns. Thankfully, as in our befuddled hands they’d have less likely to shot down the lackeys of the klepto-imperialist hegemonic order, and more likely taken our own toes out. But “this world’s crazy, give me the gun”, that sentiment captures how it all felt.

Remember the Funkadelic line “freedom is free of the need to be free”? We were the very opposite, enslaved to the need to be free, all-consumed by the burning desire to keep activism ever-aflame lest it splutter and all be lost. Like the song says “we just kind of lost our way/ But we were trying to be free.”

Set against the slow, measured piano and virtually sprechgesang vocals are those agitated cymbals. It sounds like dry kindling, one of those tracks that smoulders so much it constantly threatens to self-ignite. But it sets expectations to defy them, breaking into a more serene chorus, and the promise “one day… we’ll take life as it comes”.

Harvey proved keen to keep her sound moving. She took to pinning up a sign in the studio asking ‘Too PJH?’, a warning against repeating herself. And this was really the album that cemented all that, the freeway that always took you somewhere new.

No comments:

Post a Comment