“Hokusai has produced everything from Daoist immortals, Buddhist Gods, scholar-officials and women, to birds, beasts, plants and trees. Nothing is lacking. He captures deities with a wave of his brush.”

- From the preface to ‘Hokusai’s Sketches’, 1814

So the British Museum is back with the great Japanese print artist Hokusai, just three years after dedicating a large show to him. Which, in exhibition time, is no time at all. All due to a trove of original art, which recently turned up. And that’s more remarkable than it sounds…

From my days in comics fandom, folk were ever-keen to see original art. It could offer valuable insights into a creator’s intentions and working methods. This is a rare chance to do the same for Hokusai. In fact, exceedingly rare. The working method for prints back then was for the engraver to trace over the artist’s linework when carving into the block - creating an accurate reproduction but destroying the original. ’The Great Picture Book of Everything,’ thought to have been created between the 1820s and 40s, only survived because it was never published. We get to see this stuff precisely because his contemporaries didn’t.

You inevitably miss his use of colour, so bold and expressive. And it is a surprise to discover the size of his originals, or rather the lack of it - they’re smaller than your hand. It’s a little like imagining you’re going to see a film in cinemascopic technicolour, only to find it’s showing on an old black-and-white TV. A few are blown up onto banners, and the show even makes a point of telling us “the composition would retain its integrity on almost any scale”, but there really should be more.

As the name might suggest, this seems to have been somewhere between an encyclopedia and a Boy’s Own annual. Charmingly, it seems to make no distinction between scientific observation and myth, but bounces readily between them.

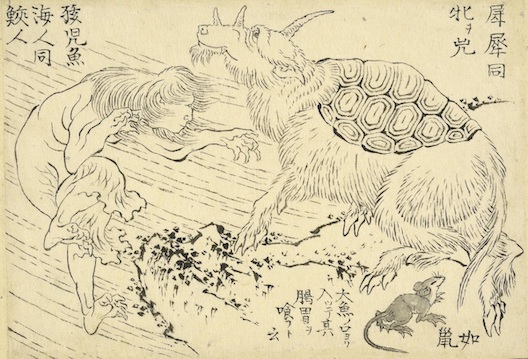

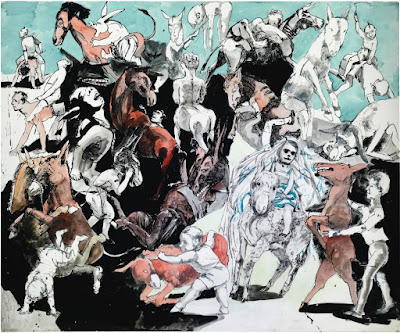

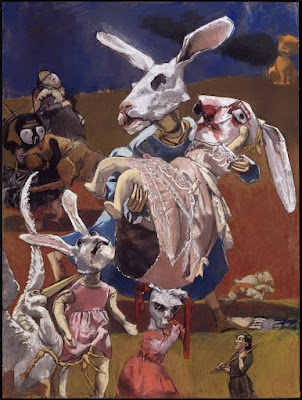

Unusually for Hokusai, but presumably because of the brief, the drawings are of figures rather than environments. Some you can even picture in an encyclopedia, ’Various Minerals and Shells’ for example is diagrammatically functional, with each individual element carefully labelled. While many are pairings so bizarre you’d think you’d wandered into some Surrealist show - ’Donkey and Seahorses’, ‘Phoenix and Peacock’, ‘Rhinoceros and Merperson’ (below), and so on.

Foreign travel was then banned in Japan, and it’s thought Hokusai never even visited its outlying islands. So when he draws things he knew to be real but wouldn’t have seen next to the entirely mythical, it’s hard to know how to respond. We’re told, for example, camels had been brought to Edo (Tokyo’s historic name). But when he depicts a rhinoceros with a shell on its back? Popular misconception, perhaps based on the notion they were related to dinosaurs? Personal artistic metaphor? Pure guesswork? Most likely, we’ll never know.

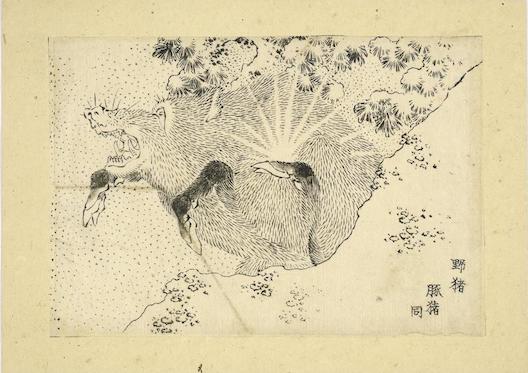

Some drawings seem executed almost like cave art, seeking more to convey the essence of its subject than place it anywhere. While others are more captured moments, such as ’Wild Boar Hunted And Shot in the Snow’ (below).

The show makes much of Hokusai’s ability to portray motion, pointing out ’A Bolt Of Lightning Strikes Virudhaka Dead’ (below) “prefigures modern manga by about a century”. Motion lines probably arose in Western comic art independently. But here they were normally used more sparingly - as flourishes, embellishments to an otherwise integral piece of artwork, like accents can only exist around letters. Whereas in Manga, they can - and do - dominate the artwork. Here, we see the radiating blast lines almost before the figure. We’re also told Hokusai distinguished between three speeds of brush stroke - formal, informal and rapid. (With ‘formal’ meaning something like ‘deliberative’.)

But there’s a twist to this. First he displays poise as well as he does movement. For example ’Two Cats By Hibiscus’ (below) accurately captures an arch-backed feline stand-off. Action scenes normally scrimp on detailing incidental objects, fearing they might distract, pushing them to the periphery of attention or eliminating them entirely. Whereas here the leaves of the bush are given as much detail as the two protagonists, as if Hokusai has no hierarchy of interests, his scrutinising eye being all-expansive.

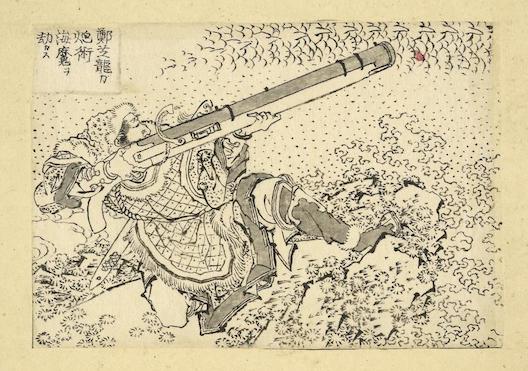

And at times Hokusai isn’t just comic art but out-and-out comical. In ’Zheng Zhilong Threatens A Sea Monster With A Gun’ (below) our hero struggles with the weight of an impossibly massive blunderbuss, which straddles most of the frame and leaves no room for the sea monster he’s theoretically threatening.

Given the brief, the show potentially tells us as much about the culture of the time as the brushwork. Though how much that culture we’re getting raw and how much is being filtered through Hokusai’s sensibilities is anybody’s guess.

And so what’s absent can as interesting as what’s present. And what’s most obviously absent? That would be us. Japan was by this point trading with the West, but holding it at arm’s length. Instead China and India appear aplenty.

Now the smartarse kids of my schooldays were keen to tell you that the popular Japanese shows ’The Water Margin’ and ’Monkey’ were actually based on Chinese legends. Which, given the subject matter here, seems pretty typical.

It’s an arguable point that civilisation effectively spread from China to Japan. (Tea and rice, for example now seem staples of Japan but originated in China.) Just as is spread to Britain from the continent. And Britain has been permeated by Greek myths and culture, in a way it hasn’t by, say, Egypt. The British Museum building itself is evidence of this, with its iconic columns and all.

Yet Japan seems much more preoccupied by China, as if it were the home of mythic time. An English-language Boy’s Own book would doubtless retell Greek myths, between gung-ho accounts of Trafalgar, taxidermies of birds and so on. But it would be understood those myths were not literal truth. This book of everything does seem much more a book of everything.

Why might this be? I’d honestly tell you if I knew! Perhaps some clue is the strong association of China with Daoism. Perhaps ancient wisdom always has to come from somewhere else, not the workaday world we inhabit.

And the India drawings have if anything a still-heavier emphasis on religion, this time Buddhism. (It’s thought both religions reached Japan before the development of Shintoism, despite the latter being native. We know Hokusai had his own Buddhist shrine.) And in the West Buddhism is associated with peaceful meditation, with looking inward not worldly change. It’s sometimes even used as an interchangeable term with pacifist.

Whereas these drawings are often of warriors! ’Buddhist Guards With Buddhist Sayings’ displays the sayings with some weapon-toting guards. Whereas Avalokiteśvara is shown in the eyes-closed meditation pose so familiar to us, but seated above a flying dragon (below).

The small number of finished prints prevents this from being a good introduction to Hokusai. Apologies to those hearing this now, but that was really the earlier show. But for those of us who saw that, this is a worthy sequel which does expand your knowledge of a great artist important not just to Japanese, not just to Eastern but to world art history.

There’s a companion mini-exhibition of, I kid not, Hokusai NFTs. I tried to not let that dampen my mood too much…