”In general it can be said that a nation’s art is greatest when it most reflects the character of it’s people.”

- Edward Hopper

Depression Invents Invention

Many commented on the Royal Academy devoting it’s (then) twin galleries to American and Russian art respectively. But it might be more significant they were based in successive decades. As we all know Russian Modernism essentially becomes derailed in the Thirties, as it collides with Stalinism. Yet that was the decade where art in America got into gear. Just as the creative spark was being snuffed out on one side of the map, it was being kindled on the other.

Modernism was around earlier, of course. As the Academy’s earlier George Bellows exhibition had shown, the Ashcan school had been operating in the nineteen hundreds and tens. But, considering how this was art for the new world and America effectively was the New World, it was not well embraced. At absolute odds to the claim America was some bastion of free speech, it faced stricter censorship than most European countries – with galleries frequently raided.

In fact it’s notable how many things we think of as quintessentially American actually start in this period. We’re told, for example, that this was the first iteration of the phrase “the American Dream”, and inevitably it came from someone lamenting it’s loss. (James Truslow Adams in 1931.)

Depressions can be… well, depressing. As the show puts it, “as the nation confronted these unprecedented challenges, it’s confidence was shattered”. But in another sense they can also be galvanising, in proving old ways haven’t worked, in forcing you to seek out the new. As Laura Cumming put it in the Guardian: “It was a terrible decade for America, and yet evidently great for its painting.” I still remember the slogan devised by another Fall, the legendary post-punk band, in the early Eighties: “New art forms hit recession cities and countries best.” Now ramp that recession up into a full-on Depression.

The change was driven by a congruence of two things. Stepped-up European migration (often fleeing both Fascism and Stalinism) included many Modernist artists. But the key thing was the Depression. In a remarkably brief turnabout, Modernism went from a marginal movement to being quite literally state sponsored. In 1933, the New Deal enabled both the Federal Art Project and the Public Works of Art Project, the nearest America ever got to the artist’s wage paid out in post-Revolutionary Russia. And yet, just as immigrants were supposed to show up on American shores ready-transformed but never did, Modernism was embraced in a strange and often self-contradictory way. Let’s start with the least modern...

Small Towns, Mighty Big Spaces

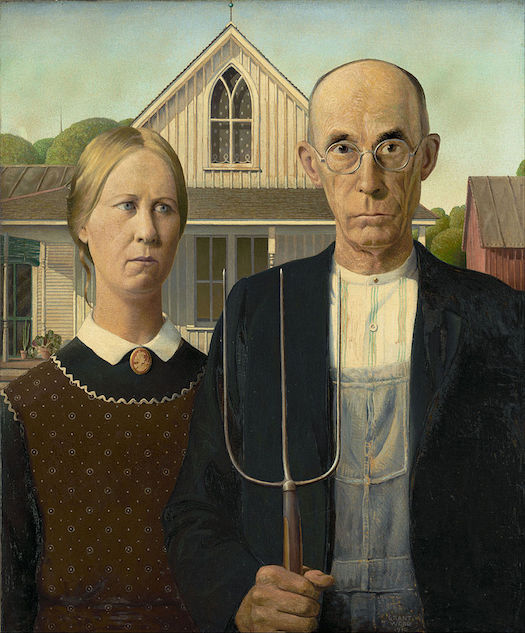

The great popularity of this exhibition was more than likely down to the inclusion of Grant Woods’ ‘American Gothic’ (1930, above). (Which inevitably made it onto the exhibition poster, up top.) If the measure of the popularity of an image is its dissemination into copies and parodies, then this work doesn’t lag far behind Munch’s ‘The Scream’. But, like a plant that requires home soil, this was its first showing out of it’s home country.

Wood started with the house after stumbling upon it, and only later added the figures which guard it so closely. And they seem almost its extensions, chipped from the same block. We don’t need to see a picket fence because the repeated three-stroke verticals essentially create one. Laura Cumming of the Guardian goes into its history and composition so throughly there’s little point repeating it all here. What matters is what’s evoked - those terse and steely, flinty people, who don’t get fat on Big Macs but save pennies in a jar. They look out at us and politely enquire if they can be helping us along on our way.

The picture’s straightforward enough, you can see what it’s of. And yet it led to the most vigorous debate over how to read it. Was Wood paying tribute to or parodying his subjects? While city intellectuals, such as Gertrude Stein, often preferred the parody interpretation the reverse wasn’t always true. When the picture was reproduced in Wood’s local paper, The Cedar Rapids Gazette, it was seen as a slight and provoked a backlash. The disagreements continue up to today, with Morgan Falconer’s article ’Tribute Or Travesty?’ appearing in the pages of the Royal Academy magazine.

In the Financial Times, Jackie Wullschlager suggests “the picture is so powerful because we can’t tell.” And it’s tempting to agree. It may well be so iconic precisely because it’s so ambiguous, because it allows each viewer to read it according to their preferences.

Yet Wood was quite unequivocal on the subject: “I did not intend this painting as satire. It seems to me that they are basically solid and good people. But I don’t feel that one gets at this fact better by denying their faults.” Which I think means something like “I respected these people, but they were strangers to me so I needed to paint them as that”. We shouldn’t assume that decides the issue. If artists were the ultimate authority of their work just because they painted it there’d be no need for them to paint it – they could just tell us what was on their minds. Which would be quicker, and I’d be less behind in these blog posts. However, here what the artist says makes most sense.

This show helps us see the work less as some great icon, whose home is in ‘greatest work’ lists, and more in its context. First, two things it wasn’t. As it was painted in 1930 try Google Imaging both ‘America Twenties’ and ‘America Thirties’. Two quite distinct sets of images come up. And this painting looks like neither of them. Perhaps it was even created out of contrariness, as an alternative to its times.

As mentioned over the Tate’s Barbara Hepworth show, this period was marked by a widespread “idealist belief in the universal language of abstraction”. And so rising to meet the latest thing from Europe was it’s polar opposite, pitchfork in raised hand. The style came to be known as Regionalism. It wasn’t enough for art to just be American, that was almost as abstract - it had to root itself in specific places. Bypassing the better-known coasts and big cities, it’s focus was on small-town mid-America. Arch-eaved houses were where you found the heart of the nation, the skyscrapers were at best the ribcage.

Charles Sheeler’s ’Home Sweet Home’, (above) painted the following year, is an interior, depopulated but which could perhaps belong to Woods’ couple. There’s a resolute plain-ness to the scene, a dislike of ornamentation, to the point where there’s almost a luxuriating in that aesthetic of simplicity. It suggests an American culture not in thrall to brash consumption but still dedicated to the pioneer spirit of the Puritans. And, much like Wood, the picture is painted in the plain style of those furnishings – there’s no separating of content from form.

Next, let’s return to Wood and look at what could be considered a pull-back view. His ‘The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere’ (1931, above) isn’t composed at all in the way the title might suggest, demonstrating his heroic historic ride. In fact Revere’s such a small figure, at first you don’t see him for the town. It’s a small American town, clustered around and dominated by the Church steeple. The cliff face behind gives it a kind of echo in the landscape. Follow back the snaking path Revere’s horse is on, and you come to the few lights on the horizon marking the previous town. The impression is of many such towns, strung along that ribbon road. As before the straightforwardness of the depiction, making it seem almost a diorama, adds to the effect.

Wood always insisted his influences came from the Flemish Renaissance. And Paul Sample’s ‘Church Supper’ (1933, above), in it’s muted palette and sense of sombre celebration, almost evokes Bruegel. And notably there’s not only another road snaking off to the next town, but it’s placed directly above the central figure (the old lady with the tray). It’s carefully shown that both towns have churches, the bell-tower to the left and the steeple at upper centre.

In both works America is not the mighty city on the hill but the small town in the valley, clustered round it’s church. And while each small town is itself a microcosm of America, it also leads to the next like nodes in a network. Every Springfield needs it’s Shelbyville. It’s the America of Capra films, where good neighbourliness derails big business simply by being closer to hand. The true America is not grandiose but unassuming, because it’s ultimately located in each citizen’s heart.

And what do you normally depict in art? The stuff you see around you, or the stuff you used to? Between 1890 and 1930 the population had doubled, with more than half now living in cities. In the show’s words Regionalism “lamented the disappearance of the settler mentality”, just as the Romantics had lamented the dying of folk traditions. (Indeed some works, such as Wood’s ’Young Corn’, 1931, could easily be set in England.)

The show’s title is well placed. Just like the original Fall myth, this is an origin story, and where it went wrong is also where it all began. Like a microcosm of his country, Wood was born in rural Anamosa, Iowa, but was then moved to the big city at the age of eleven, after his father suddenly died. It was nostalgia for that rural life which fuelled his art, even driving him to write the pamphlet ‘Revolt Against the City’ (1935).

Is nostalgia always reactionary? Thomas Hart Benton’s ‘Cotton Pickers’ (1945, above) is the only Regionalist work in the exhibition to show black people. In fact the whiteness of the cotton and the work-sacks they haul emphasises this. Their work is hard. By the pickers a baby lies in a makeshift shelter, while even the figure offering water is slightly bent. Behind them, that wagon has a slope to climb - emphasised with an echo in the curve of the clouds.

However much it was verbally venerated by white Anglo-Saxons, the hard work that built America was actually provided by successive waves of immigrants. Active on the Left, and typically for a New Deal artist primarily working on public murals, Benton’s solution to this is to transfer that spirit of industry to black workers, to emphasise how they are Americans too.

Yet unlike elsewhere the workers are de-individualised, only the water carrier showing their face. Most cotton pickers were share croppers, forced to sell only to their landlords. Who, unsurprisingly, often exploited their position. All of which is absent from this image, suggesting they were the beneficiaries of their own hard work. The romanticism inherent to Regionalism screws with Benton’s documentary impulses, there’s no place for black faces even in the faded American dream. (He often complained how he’d alienate European-looking Modernists with his politics and the art market with his “folksy” style.)

‘Roustabouts’ (1934, above) by Joe Jones, another Leftist artist, might be a more honest depiction, showing a group of black workers with a white boss standing over them. The ones shouldering the heavy bags have presumably more recently received their orders. And it may be no co-incidence that this work uses an urban location. With it’s cross-river view and belching chimney, it semi-echoes Bellows’ ‘Men of the Docks’ (1912).

It’s unremarked upon by the show, but Alexandre Hogue’s ’Erosion No. 4, Mother Earth Laid Bare’ (1936, above) is surely a commentary on Wood’s ’Fall Plowing’ (1931, also above). Both give a gradated view of a landscape, with the horizon line at about the same height. Both contain a farmhouse but no people. Yet Hogue turns Wood’s plough the other way, as if a reversal of the image.

In the gap between the two works the dust bowl migrations had begun, where migrants were forced to flee the now uninhabitable great plains. As Hogue points out the causes were as much human as fluctuations in weather patterns, as over-intrusive farming methods stripped away topsoil. Here the land takes on a woman’s contours, and the plow comes to resemble an instrument of rape.

Admittedly it’s not a very good painting. Even were we willing to accept the gender essentialist concept of ‘Mother Earth’ (which we’re not), there’s an uneasy mixture of heavy-handed righteousness with a rather furtive sexual fascination. While there’s not enough of an attempt to challenge Regionalism’s rather neat and tidy view of nature, pushing the work into an uncanny valley. That ‘earth’ looking more like foam rubber. But it is historically interesting, an attempt to counter Regionalism’s illusory idylls.

The City On the Hill

The two things Wood most definitely wasn’t doing, the urban as a signifier of the modern and the tendency towards the universalism of abstraction, are neatly put together in Charles Green Shaw’s Wrigleys’ (1937, above). And yes that is a stick of chewing gum he stuck centre; in this land of free enterprise, he was trying to win an advertising competition. The result is, to quote the Royal Academy magazine “as if a pack of gum had zoomed in on an early Rothko”, or like one of those gag cartoons where the Mona Lisa beams unenigmatically as she hawks toothpaste.

A remarkably similar cityscape appears on the upper right of Aaron Douglas’ ’Aspiration’ (1936, above). As the silhouetted figures look up to it the City becomes escape, Oz to your Kansas. The image of… sometimes just the term ‘city on the hill’ became something of a stalwart of American discourse. It stems from a sermon of Jesus’ from Matthew: “You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden."

In other words, Christians have the obligation to act in an exemplary manner. (The proverb “don’t hide your light under a bushel” stems from it.) Yet what seems to have popularised the phrase in America isn’t behaviour so much as place - the association of the futuristic city with the radiance of heaven. America lit the world like beacon. And its cities lit America.

(And in fact I’ve placed this section second partly to convey the notion of the city framed by the country. As said of the Bellows show, he “had to see those soaring skyscrapers and teeming streets with an outsider's eye, the better to convey them to the rest of us.”)

Take in the painting as a whole and several schematics can be seen at work, overlapping one another, all journeying from lower dark to upper radiance. As above, it could be seen religiously, as turning to the light of the Church. Or it could be through time, those shackled hands at the base clamouring to escape the darkness of slavery. Or through space, the journey from South to North, or rural to urban.

The two were in practice combined, in the Great Migration (possibly the world’s biggest peacetime migration) many black Americans migrated from the segregation of the rural south to relative opportunity in the industrial north. Which could be seen, provided you took it from the right angle, as a whole continent of Whittingtons turning towards the city in order to seek their fortune. Or, more widely still, a timeline of human evolution, from the darkness of tool-less hands to the light of modernity. (Look at what the centre left figure clutches.)

And it’s through this multi-mapping that blackness comes to be associated with the primitive, and ‘lightness’ with resolution. In other words, uh-oh. At its most extreme, it might be read as dark-skinned people being washed white. Yet this work was made by a black artist. Douglas was strongly associated with the Harlem Renaissance, which asserted the value of black culture in American life, but which in the process came to be criticised as assimilationist. It seems a long way from the “black is beautiful” aesthetic of the Sixties and Seventies. (More of which coming up.)

Exhibiting in the uber Modernist Armoury Show exhibition, staged in New York in 1913, could scarcely be more of a contrast to Wood’s Regionalism. Stuart Davis’ ‘New York – Paris No. 3’ (1931, above) presents the city as somewhere between a pattern and a collage of elements. And this style fits the city more readily than it would the country or small town. We don’t think to ask why gas pumps might be the size of three-storey hotels. Painted after Davis spent a year Seine-side, the picture’s less a contrast than a comparison of New York to Paris. And while Reginald Marsh’s ’Twenty Cent Movie’ (1936, also above) isn’t a collage but a street scene, it’s such a busy jumble of elements, including frames within frames, it has much the same effect.

Whereas Edward Hopper’s ‘New York Movie’ (1939, above) though only varying the setting by taking us inside a movie theatre, has much the opposite effect. This work is all about space and stillness. A central column bisects the painting, even giving the two halves their own light sources. The woman, who we have to take for the main figure, is pushed to the side of the composition. Though handily lit by a lamp, her face is pushed into shadow. Over the other side, we see only a slither of the silver screen. The blue uniform, highlit by that thin red stripe, would mark her out to contemporaries as an usherette. She’s a worker there, yet she’s passive and pensive.

And what’s she thinking? We don’t know. How could we, when she’s just paint on canvas? Yet Hopper makes that a mystery at the core of the work. Hopper disliked comparisons to Regionalism. A point he might over-argue, that quote of his up top is almost the credo of the scene. But he was correct in seeing his style as more psychological than parochial.

He styled himself after Manet and Degas, but I was reminded more of another of their disciples – Walter Sickert. It’s true he has a much smoother painting style, and his regular guys and everypeople are some way from Sickert’s rootless cosmopolitans and angsty bohemians. But like Sickert, he tended to paint the space between things rather than things themselves.

The show then smartly hung his ‘Gas’ (1940) the other side of a doorway, and indeed they work well as bookends. Hopper makes much of the twilight setting, with the light that plays through the door and windows of that gas station cutting across the frame. The main figure is again solitary, but this time is placed at the centre of the frame. He’s smart-dressed and dutiful; in fact, never in history has a gas attendant looked more like a sentry. We’re asked to assume both figures are beset by the same existential crisis, but one knows the solution is to act your way out. One setting being rural and the other urban… that’s probably as significant as one being male and the other female.

A Dream To Some...

Finally, in the section ’Visions of Dystopia’ the show looks at the works which most literally took the Depression as a Fall. To them, the phrase “the American dream” was only a cue to the most grotesque and nightmarish visions.

Superficially, in it’s insertion of various figures into a scene, ‘Dance Marathon’,by Philip Evergood (1934, above), resembles Marsh. But this work is much more reminiscent of German Expressionism, as a series of grotesque couples lean heavily against one another, the couple at the centre looking crossways. These events were a Depression phenomenon, an endurance version of showbiz later immortalised in 1969 film ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They’. The radiating blocks of the dancefloor make them appear as if trapped in a spider’s web.

America liked to present itself as full of youth and vigour. Here, even the audience looks tired and isolated. And we’re placed among them, hands grasping the bar before us, making us implicit in this voyeuristic spectacle. But then against this naturalising gesture, at upper left it’s skeleton fingers which holds out the prize money. (Adding to the grotesquery, above the hands at lower right appears to protrude the face of Boris Johnstone. Well, he does have dual nationality…)

The damage the Depression did was severe, but had strange upsides. Despite it’s extremism and associations with violence, the Klan had for many years been able to present itself as a mainstream political organisation. (It’s peak membership year had been 1925.) However, the Thirties were to mark a drastic fall in their fortunes. And an image such as Joe Jones’ ‘American Justice’

It’s not a great painting, not the match of Jones’ earlier-seen ’Roustabouts’, still less the visual equivalent of Billie Holliday’s (recorded 1939).

Lurid cartoonishness belies its seriousness of purpose and its documentary message is marred lack of consistent lighting; it’s like a tabloid that thinks it’s a broadsheet. But as with Hogue its significance is cultural.

And if the Depression wasn’t bad enough, then came warning of war from Europe. With its title and central masked figure, Philip Guston’s ’Bombardment’ (1937, above) may seem reminiscent of Picasso’s ’Gunernica’ of the same year. And both were visceral reactions to Francoist bombing.

But it’s actually not a collage of elements. It just uses its circular shape to distort and dynamise what would otherwise be pictorial space. Unlike Picasso’s allegorical take, here real planes blast a real street. The bomb is going off dead centre, actually some way from us, but yet the blown figures are flying out so far they’ll surely whack us. War, it seems, is headed this way. The story of Guston abandoning Abstract Expressionism for cartoony representation is so strong, there’s a tendency to overlook his earlier work from this era. The tendency’s understandable, but mistaken.

The bridge is almost as iconic an image of urban America as the skyscraper. (Think of how often they showed up in the Bellows’ show.) San Francisco’s Golden Gate bridge had only been finished two years before. So of course O. Louis Gulgliemi’s ’Mental Geography’ (1939) takes it to Brooklyn Bridge. The date might suggest that like Guston he’s playing on fears of war winds blowing West, yet what he does is subject it not to artillery but Surrealist distortion - what Dali did to clocks.

The expanse of sky above it’s crest suggests it’s an act of hubris which God has now confounded. The child figure looking up at it has a bomb protruding from her back. War has made hybrid creatures of us, we’re part victims of its weapons and part weapons ourselves.

The smaller Sackler gallery is perhaps best suited to solo artist shows. Attempts to embrace vast themes soon run up against it’s constraints. Things here aren’t as crammed and inadequate as in the earlier ‘Mexico: A Revolution In Art’ exhibition, but this tour is still sometimes too whistlestop. The last section, on post-figurative art, is precisely five paintings long – like they miscalculated and ran into a back wall when they hoped for extra time. It’s better read not as a part of this show but a “coming soon” trailer for what happened next.

(I read later, in Sarah Churchwell’s piece in the Royal Academy magazine, that the Paris version of the show ended with a montage of Depression-era movies, including the Emerald City from ’Wizard of Oz’. It’s a shame there was no space for that here.)

But then let’s be grateful for what we got. In the Guardian, Adrian Searle exulted “there is terrific range in style and subject matter, outlook and temperament, artistic registers, ambitions and focus here.” And he’s right. There’s perhaps not the limits-busting range as seen in ‘Revolution: Russian Art’, but the sense of tumultuous times generating creativity still hits you.

And like the Russian exhibition the works vary dramatically in quality, all the way from sublime to awful. And like the Russian exhibition this really doesn’t matter, or at least anywhere near as much as it could do. Art seems so broken with the past, so new that you need to allow for it still feeling its way. You look at works for what they were evoking, for what they say about their times. Your brain needs to keep switching between aesthetic, political and cultural concerns. But so be it. That’s as much a strength as a weakness.

But then let’s be grateful for what we got. In the Guardian, Adrian Searle exulted “there is terrific range in style and subject matter, outlook and temperament, artistic registers, ambitions and focus here.” And he’s right. There’s perhaps not the limits-busting range as seen in ‘Revolution: Russian Art’, but the sense of tumultuous times generating creativity still hits you.

And like the Russian exhibition the works vary dramatically in quality, all the way from sublime to awful. And like the Russian exhibition this really doesn’t matter, or at least anywhere near as much as it could do. Art seems so broken with the past, so new that you need to allow for it still feeling its way. You look at works for what they were evoking, for what they say about their times. Your brain needs to keep switching between aesthetic, political and cultural concerns. But so be it. That’s as much a strength as a weakness.

No comments:

Post a Comment