”This exhibition follows

Wassily Kandinsky’s intriguing journey from figurative landscape

painter to modernist master, as he strove to develop a radically

abstract language.”

Sometimes it’s all too easy to react.

What’s more, the rarified air of galleries can stir this in you.

You find your brain vying with the documentation and curatorial

efforts, as if they’re all part of some conspiracy conjured up to

keep us apart from the pictures. (Albeit a conspiracy conjured up by

the very people showing us the pictures.) I do this myself and I know

I do.

Of course the world has no shortage of

educated idiots, and with Modernism in particular there’s aspects

that are almost always (if not consciously) suppressed. But if all

you do is react you’re never actually acting – you’re just

being somebody else’s mirror image. It’s more likely the problem

here lies in reducing art to mere words, and in so doing tying it

down to a neat narrative.

‘The Path to

Abstraction’ is more a sound-bite concept that fits

neatly on a poster than some plot. But it's still reducing

Kandinsky's career to a “path”, a “journey”, a series of

linear “developments” we can cut up neatly into successive rooms

like marking it out with milestones.

The exhibition “focuses on the early,

exploratory period of his career, as he moved from early observations

of landscape towards fully abstract compositions.” (So says Kate

Pau in the catalogue). The first two rooms therefore offer us the

Fauvist Kandinsky, but their benefit in being there lies in

“offer[ing] a foretaste of his later explorations into the use of

colour”.

This skating over Fauvism is so common

as to be almost orthodox. Fauvism is like the middle child who parent

attention skipped over. Indeed, it suffers from something of a double

whammy. See Modernism as a linear series of formal innovations and

Fauvism becomes incidental, a staging-post, a way-station on the road

from Impressionism to Expressionism. On a more popular level,

Fauvism lacks the big hitter that can turn a Tate show into a

blockbuster. No Monet, no Picasso, no Dali. (Matisse is the exception

to the rule, except he’s rarely popularly associated with Fauvism.)

Personally I find Fauvism, with its

solid blocks of bright and often unexpected colours, somewhere I’m

happy to linger. (See for example 'Landscape With Factory

Chimney', 1910, above.) I enjoy the similarity not just

between it and folk art but much commercial art. (Commercial art

presumably uses the style more due to skimping on printing processes

than any fancy philosophising. But then so did folk art.) But mostly

I just enjoy it, the juxtaposition of realist and

non-realist styles appeals to something deep in my brain I couldn’t

vocalise. (Something Kandinsky himself would have been proud to

hear!) I even found myself taking a guilty pleasure in the

perspectives used, the key element expunged by abstraction, like

indulging in the last piece of chocolate before Lent.

Try this for an angle: “Kandinsky’s

paintings during the years immediately preceding the First World War

often convey a dramatic sense of a world on the verge of destruction…

An artistic revolution was also underway, with Kandinsky emerging as

one of the key figures.” Now just wouldn’t that make a great

montage on 'The South Bank Show', World War One

trenches morphing into Kandinskian colour and all that? From this

angle the pictures are scanned for elements representing cannons and

swords, as if it was the violence of the world around him which drove

Kandinsky off into the arms of the abstract.

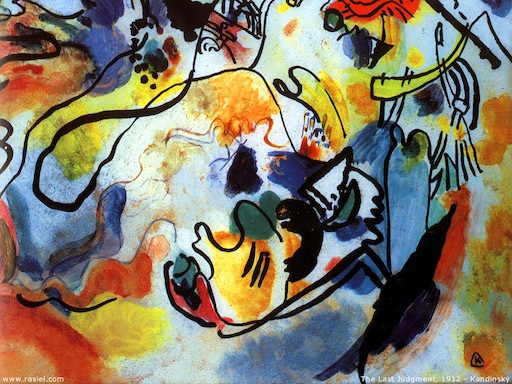

In 'The Last Judgement'

(1912, above), for example, a figure is described as cowering before

a trumpet. Now there are dark paintings on show here, but they all

follow a fairly simple code. One of the codes is that they’re

always …um… dark. This one could hardly be painted in brighter

colours and still be visible without sunglasses! Moreover, the

“cowering” figure may possibly have her hands over her ears, but

could as easily be said to be kneeling in prayer. Compositionally

she’s not recoiling against the trumpeter but facing the same way.

It’s like they’re alongside each other.

Certainly, Kandinsky was no bloodless

New Ager who shied from savagery. All his works of this era have a

dynamic, convulsive quality, and there’s often a sense that they

are storms. But there’s a greater, and finally overpowering, sense

that they are dances.

I see Kandinsky as a more spiritual

than political figure, always asking what was universal and rarely

what was particular. With bombs going off around him, he’d probably

just ponder the mystery of the purple rectangle regardless. I don’t

imagine war somehow ‘abstracted’ him from the world and I don’t

think he was ‘driven’ down that path in any case. If there is a

narrative journey towards abstraction here, it’s one of revelation

more than damnation.

His great compositions have a sweep and

swirl to them. (See 'Improvisation Gorge',, 1914,

above.) As you stand before them you won’t fix on their entirety so

much as take in one then another element, you eye being pulled

backwards and forwards like exploring a city across it’s

criss-cross tramlines rather than surveying it from outside and

above. His favourite Biblical image, the deluge and flood, is partly

a metaphor for the journey from solidity to swirling liquid.

If the

hippies hadn’t run off with the word, we’d be able to call

Kandinsky truly cosmic. The transition from Room One (Fauvist) to

Room Nine (Abstract) merely mirror the changes he hoped to see in the

world, changes he hoped to help magic into being by depicting them.

He’s not fearing apocalpse but pining for revelation, the time we

can just cast off the outer forms which divide everything and

inter-mingle.

Kandinsky asked the viewer, should they

notice any representational elements, not to comment on them. But

there’s more to this than just good manners, like not telling the

critic whose just been on the Late Review his flies were undone. The

best way to approach these impressions, improvisations and

compositions is to just go with the flow, open yourself up to their

suggestion. If one thing looks like a face, a boat or a ladder and

another just the sweep of a line, don’t dwell too much on the

distinction.

In life our sight passes between

'abstract' and 'non-abstract' images all the time. Walking down the

street our eye might flit betwen on a pattern of cracks in the

pavement and a tree or a shop window. This doesn't cause us much

concern, so I don't see why it should if the two things were in a

painting.

Pretty soon the sense that these

pictures aren’t completely abstract, and the attendant notion that

it’s hard to tell when they are from when they aren’t, stops

being a problem and starts becoming part of the pleasure of looking

at them. It’s like listening to a song or reading a poem. By seting

yourself the task of deciphering it you’re just going to bypass the

point for the sake of a thousand trivial details. We’re here being

asked to do the same thing the other way up, expunge the

representational for the sake of the abstract. But it is the same

thing – and it’s not the most useful thing.

And all art is

abstract if you choose to look at it that way, an arrangement of

lines and coloured shapes on a canvas. Abstraction in art is like

ambience in music, more a way of looking at or responding to art than

a way of creating art. Even if some works try harder to evoke such a

response, all can be responded to that way.

Equally our eyes are adept at picking scenes and images from clouds

or out of the grain of wood. When we stop to look at a painting we

can sometimes listen to the polemicists more than we do our own

senses. We shouldn’t.

Partly the problem comes from the

‘ism’-ness of Modernism, which in a way was the supreme ‘ism’.

Modernism was widely written about, in fact in some ways it

existed to be written about in a way previous art

movements hadn’t. The art most written about is often that which is

most easily written about, which takes a concept or theory and

exemplifies it. But the art best remembered

is often that which takes a bunch of seemingly incongruous or even

contradictory concepts and notions and holds them in perfect balance.

This problem could even turn inward,

like a particularly nasty toenail. Modernists frequently felt obliged

to come up with grand high-faulutin’ theories to justify their

daubs, and it wasn’t always to the work’s benefit. Mondrian was a

classic example of an artist who was far better when just flailing

around, before he boxed his thinking up into his grand scheme.

Kandinsky wrote voluminously, if not

always coherently. But perhaps the secret of his talent is that he

was willing to follow his nose. Draw something over and over, and

pretty soon it will start looking more and more codified. When you

see yourself doing that, you can fight against it (like you’re

supposed) or go with it to see where it takes you. I suspect the

origins of Kandinsky’s abstraction lie far more in such roots than

in any grand narrative of advancing art.

And his paintings are great not because

they finally reach the point where they expunge the representational

for the abstract, but because they mix the two up so... well, I think

the word is carelessly, though in the positive

sense. Ernst employed a thousand tricks and devices to leave the

viewer unsure what they were actually looking at, as it created a

potent ambiguity and forced the viewer to take a far less passive

role. Kandinsky just swung it like a natural. His great paintings are

like that song or poem you figure must be

about something but can never quite pin down to what,

so you always want to go back to it.

Perhaps another weakness of this “path

to…” stuff is that we only get one tiny room at the end for the

later, geometric Kandinsky (such as 'Circles On Black',

1921, above) – as a kind of post-script. Of course there might well

be too much to the man’s career than could be captured in a single

exhibition, but there’s significance in fixing on the beginning and

middle of the story rather than the finale. These Bauhaus-era works

may appear more stately, more considered than the convulsive early

abstracts but ultimately they’re my personal favourite Kandinskys.

Coming Soon! More on

abstraction and semi-abstraction in the arts...