(This, I'll have you know, is

Lucid Frenzy's five hundredth post! Don't you get a telegram from the

Queen for that? Perspective paradoxes may make it appear to go up

after the exhibition has closed)

“I cannot help mocking all

our unwavering certainties... Are you sure that a floor cannot also

be a ceiling? Are you absolutely certain that you go up when you walk

up a staircase. Can you be definite that it is impossible to eat your

cake and have it?”

Compelling impossibility

It may be fitting that the first time I

encountered Dutch artist MC Escher was through a popularised,

bastardised copy. As a child I won a drawing competition in a comic.

And unbeknownst to my young mind the poster prize, which soon adorned

my bedroom wall, ripped off his images wholesale. Their compelling

impossibility fascinated me. If you looked at them hard and long

enough, surely they resolved back again into something resembling the

laws of physics. My unwavering certainties were well and truly

mocked.

But here's the real thing. This being

the first major British exhibition devoted to Escher, its like Lowry all over again. With it's audience-attracting

adjective “amazing” the show sold so well I was lucky to get a

ticket. While the critics proved once more that the corollary of

popularity is critical disdain. In the Telegraph Alistair Smart dismissed him as “the sort

of artist you leave behind in your twenties… offering nothing in

the way of emotion, expression or depth – just little games that

grow tiresome when seen together on a large scale.” While Ben Luke, taking up Brian Sewell’s mantle in the Standard, scoffed “a great illustrator? Perhaps, if you like this kind of

thing. But a great artist? Not on your life.”

You can particularly hear his lofty

disregard in the use of the lowly i-word. In fact Escher may attract

a perfect storm of critical antipathy. He mostly worked with prints,

and while he limited his editions that wasn't enough for an art scene

so fixated upon the original. Plus, as the show states he had “little

to do with the main thrust of Modernism”, which makes him hard to

fit into the neat lineages they so dutifully curate. And like Lowry

the feeling may well have been mutual. Escher's standard response to

critical analysis was to rebuff it. His motifs, he insisted,

contained “no symbolic meaning whatsoever. I put them there only

because I like them”.

Yet if popularity keeps the critics at

bay, it can bring its own problems. Wikipedia has a well-populated page devoted to uses of Escher in popular culture. But these homages often do the opposite of my

bedroom poster, invoking his name but reproducing him in at best a

reduced format. Major elements of his art are often entirely absent,

he becomes simply a shorthand for gravity being applied locally to

different planes. In short Escher means walking the walls, which

confuses him with Spider-Man. We think we get Escher. When the very

point is not to.

He's most often associated with the

Surrealists, who were his contemporaries. Yet like Joseph Cornell

this misunderstands his art. Perhaps even more so for, unlike

Cornell, he didn’t even associate with the group - corresponding

not with British Surrealist Roland Penrose but his mathematician

nephew Roger. In fact he isn’t a Surrealist for reasons very

similar to Cornell. As said of the Cornell show:

“Surrealist

artworks tend to be about bursting the barriers between dream and

wakefulness, between the conscious and the unconscious, so have a

tendency to erupt with lurid and provocative imagery.”

Which

isn't Escher at all. Even 'Dream' (1935, above),

perhaps his most Surrealist work, has arches and avenues which

reflect the moonlight calm of de Chirico rather than the mad mid-day

sun of Dali. (Overall, the nearest Surrealist to him was probably

Magritte. Their work shares a deadpan quality which provides a

pseudo-seamlessness, delivering the impossible as though it was the

everyday. And both men topped that off by cultivating a staid,

anti-bohemian persona. But more of that anon.)

And all that separated him from

Surrealism became twice as true for the later psychedelic generation.

Escher’s reaction to hippie adulation was roughly similar to

Tolkien’s, and went along the lines of “you damn kids get off my

lawn”. In the now much-traded story, he refused the Stones

permission to use his art for an album cover because Mick Jagger's

letter had improperly addressed him by his first name. That may well

have been not just an anecdote but a rescue. His art didn't belong

there, and perhaps when seizing on that surface detail he intuitively

sensed it didn't.

In fact, in one of the biggest

surprises of the show, Escher's nearest relations were the Cubists,

even if he doesn't fully imitate their crazy paving. The early

'Portrait of Pieter Jan Zutphen' (1920, above),

combines the Cubist fracturing of an image into planes with the

poster artist's building of object up from blocks of colour and

shade. 'Other Worlds' (1947) superimposes

different views of a single scene (above, straight on and below) into

one. Much like Cubism, Escher's art is about art,

about how we depict and how we see things.

But the show makes a convincing

argument that his chief influence was not an art school but a place -

the landscape and architecture of the Mediterranean world. First

visiting there at the turn of the Twenties and living in Italy from

'23 he at first faithfully delineated the views he found, fully

obedient to all known laws of physics and gravity. Some works from

this era even stray into folk art, for example 'Corte,

Corsica' (1928) with it's vertical arrangement of fields in

the background.

Despite the critics, like many of his

prints Escher was multi-faceted, and to see him you need to take in

them all. His art, so much about metamorphosis, metamorphoses itself

between various themes, and looks at things from different angles

without ever finally settling on anything. Trying to capture him

isn't really so different from trying to resolve one of his warped

perspectives, and as you struggle with it you can hear his mockingly

straight-faced insistence there's nothing to see. I'm going to say

here he had five faces, in increasing order of importance, but as

everything shifts and overlaps in practice you might see more or even

less.

The Great Architect

With the well-known 'Tower of

Babel' (1928, above) Escher took what he called a “bird's eye view”

of the subject. However in an old post I saw a different set of eyes at work:

“The crest of the Tower is

looked down upon, an impossible angle for any human which suggests

God’s perspective. God is not just the only named character in the

Genesis passage, there’s even the suggestion he one day comes

across the Tower. (‘Then the Lord came down to see the city and

tower which mortal men had built.’) …Escher’s etching could

therefore be of the moment in Genesis where God spies the Tower and,

in a mixture of outrage and alarm, sabotages its builders by tying

their tongues.

”

In short, Escher is seeing things from

God's perspective. And when he draws himself he dominates his

environments, while almost all his other figures are diminutively

placed in a habitat. For 'Self Portrait' (1923,

above) he was still a young man but a combination of style and medium

make him look older, more authoritative. It could almost be a Bible

illo of Abraham or Moses. Those staring eyes, which the radiating

linework emphasises, often recur in his owls - another frequent motif

of his.

We should notice how recurrent the

paraphernalia of religion is in his work, how often we come across

monks and temples. And we should remember that Escher originally

studied to be an architect, while God is often referred to as “the Great Architect”. He

often puts himself into what are virtually creator poses. 'Hand

With Reflecting Sphere' (1935, used as the poster image of

the show, seen up top), can be read both as the Earth in the

creator's hand and Escher at home in his study. He holds the world up

while he's at the centre of it. It reflects chiefly his face -

monarch of all he surveys. After those early years the only fully

realised figures in his work are himself and, occasionally, his wife.

The others are little more than ciphers, a depersonalised populace

for his environments.

This of course risks banality. All

artists make stuff, and they frequently depict themselves at work as

artists. But its not just the frequency of the images. This combines

with the way he isn't arranging scenes but constructing worlds. The

word “world” is almost as important in the show's title as

“amazing”. He builds as much as he delineates.

These works have their own reality, even down to their own rules of

geometry. Escher is creating his own reality systems. If he is to be

a deranged God of his private realm, one who cries “let vanishing

points be bendy” then so be it. It's his world and anything he says

goes.

The Escape Artist

Though apolitical by nature Escher came

to distrust the increasing conformity of fascism and in 1935 he left

Mussolini's Italy. From there, deprived of the Mediterranean scenes

from which he drew inspiration, he started to invent his own - in his

words - “mental imagery”. He was, in short, thrown back on his

mind's eye. (Though he did produce fantastical images before then,

the show suggests this as a spur which pushed him further in that

direction.) And what better way to elude your enemies than tangle the

rules of perspective after you? Perhaps his insoluble puzzles were

his priest holes and escape hatches.

While this might seem to contradict

Escher as the Great Architect, in many ways the two fit together

neatly. It's often being out of place in this world that leads an

artist to create their own. Escher was even less of an outsider

artist than Cornell or Edward Burra, a tag which fits neither of them to start with. In a

career sense, he was a successful commercial artist. But he kept at a

remove from the art world, rigorously ploughing his furrow with total

disregard for its fads and fashions. He meticulously built up his

works, and pursued a private image repository over many years. That

hermeticism makes him something like an outsider artist with a bank

account.

Yet taken too far, this might suggest

someone pushed out of the world, an exile from reality. It doesn't

explain why, after the War, he didn't return to the Med or at least

resume his travels. More importantly, despite their undoubted

otherwordliness its inadequate to see his works purely in terms of

escapism. For all his feigned innocence and deflection of attempts to

analyse him, he said this quite explicitly:

“The primary purpose of all

art forms… is to say something to the outside world; in other

words, to make a personal thought, a striking idea, an inner emotion

perceptible to other people’s senses in such a way that there is no

uncertainty about the maker's intentions.”

The Cartographer of

Transformation

Even if they don't make his greatest

hits, Escher's works frequently featured tessellating forms. These

forms by their nature made up each other’s outlines, like countries

sharing borders. Breaking from the art convention that objects are

discrete from one another, from the “my outline belongs to me”

rule which can feel a basic presumption of art. (Portraiture, for

example, is dependent upon it.)

While he often made repeating

tessellations such as 'Regular Division of the Plane With

Reptiles' (1942), let's focus here on those that morphed.

Let’s remember that Cubism was the sole Modernist movement to catch

Escher’s attention, and that Cubism associated itself with

Relativity and other scientific developments. (Even if the

connections they made were more poetic than actual.) Similarly there

may be a general association between Escher and the less solid, more

uncertain world being discovered by developments in physics. (He even

called a print 'Relativity', one we'll look at in

more detail later.) But in particular, he became more and more

interested in morphology. (Chameleons became a common motif.)

'Encounter' (1944,

above) is almost the opposite of of the dumbstruck workmen in

'Tower of Babel' - here two figures come to life

and meet. The black figure in particular rises progressively from all

fours with each iteration, like the famous evolution diagram of a

monkey becoming a man.

And evolution became a recurrent theme.

Evolution is often popularly supposed to be teleological, like a

gradualist method of assembly. And as in the example above Escher can

conforms to this. It's also true of 'Development II'

(1939, above) which uses abstraction as a kind of primordial soup

from which form emerges, the fully realised lizards seemingly walking

off the edge of the print. But its a reversal of this which wins out,

such as the 'Circle Limit' series of the late

Fifties and early Sixties, where the realised figure is at the cente

of the image and shrinks in size towards the edge, like a pattern on

a ball.

And with this his streets became two

way. Or in the case of 'Verbum (Earth, Sky and Water)'

(1942), three-way. In a composition almost like a chart or table, you

can read outwards, the rays of creation building for example into a

frog. Yet you can as easily read sideways, so that frog might morph

into a fish or bird. While 'Metamorphosis II'

(1939/40), were it not more than four metres long, could be displayed

in a loop.

Escher articulated this cross traffic:

“We can think in terms of an interplay between the stiff,

crystallised two-dimensional figures of a regular pattern and

the individual freedom of three-dimensional creatures capable of

moving about in space without hindrance. On the one hand,

the members of planes of collectivity come to life in space; on

the other, the free individuals sink back and lose themselves in

the community.”

The Cartographer of Cosmic

Balance

Alistair Smart sees Escher as “unquestionably pessimistic – or, if you

prefer, absurdist – his figures not so much individuals as clones,

usually trapped in nightmarish scenarios.” And it’s true that

there's little to distinguish the faceless drones

of'Relativity' (1953) from the centipede creatures

of 'House of Stairs' (1951), displayed adjacently

in the show (and here, as above). The moss garden of

'Waterfall' (1961) suggests diminutive

micro-worlds, adding to insect associations.

And with that comes a definite ordering

to things. As said of Lowry, he “painted environments then placed his

figures within them… like animals in a habitat, like flocks of

birds in trees”. And this makes his creatures inscrutable. He

wrote that the figures in 'Ascending and Descending'

(1960) “appear to be monks, adherents of some unknown sect” - as

if he has no more clue than the rest of us. When his work is

duplicated in film, animation or computer games, when characters or

game-players have to be beamed from our world into one of his

environments, this distancing is shattered and something vital is

lost. We need to stand outside his prints, looking across an

uncrossable threshold, as much as we did Cornell's shadow boxes.

Plus, Smart's does seem to be a common

reaction. I overheard one attendee confessing she found Escher

nightmarish as a child. And yet many others had purposefully brought

their children, and were exultantly pointing out the logic puzzles to

them. Perhaps Escher is simply Marimitey. And perhaps my reaction was

set at an early age, by that poster on my bedroom wall. But while, as

with any artist everyone has their right to their own Escher, I claim

my Escher to be closer to Escher’s Escher.

For those figures never seem lost

inside their environments, like Harry Potter befuddled on the stairs

on his first day at Hogwarts. Instead they belong in them, are able

to navigate them. It's our separation from them which makes the

experience absurd, the way our perplexity contrasts with their ease.

Our world makes sense to us, and theirs to them. How can this be

reconciled?

If absurdism is at root the denial of

inherent meaning in the universe, Escher could by contrast sound very

much the optimist. He said “the desire for simplicity and order

helps us to endure and inspire us in the midst of chaos. Chaos is the

beginning, order is the conclusion.” Or, perhaps less certainly

“Chaos is present everywhere in countless shapes and forms, while

Order remains an impossible ideal, the exceptionally beautiful fusion

of cube and octahedron doesn't exist. Nevertheless, we can always

hope.”

As ever in art, order is associated

with symmetry. And there's a kind of thwarted symmetry to 'Tower

of Babel' with the two matching black-and-white harbours in

the upper background, which then triumphs in the handshake of

'Encounter'. (Which Escher described as “a black

pessimist and white optimist shaking hands with one another”.) And

this yin/yang of black and white recurs quite frequently, for example

in 'Day and Night' (1938, below.)

And this is visible in some of his more

cosmological prints, for example 'Double Planetoid'

(1949, below) which shown the human and animal worlds co-existing,

towers and dinosaurs side by side. 'Circle Limit IV (Heaven

and Hell)' (1960) is perhaps the pinnacle of this tendency,

showing an angel and devil perpetually interlocked.

And in his art the “exceptionally

beautiful fusion of cube and octahedron” did exist. This seems to

have been a totem of Order for him, the hexagon and square polyhedral

presented as a kind of ur-shape, a universal template out of which

all else can emerge. It's visible in 'Crystal'

(1947, below) or topping the towers in 'Waterfall'

(1961). In the last example he specifically warned the viewer against

any attaching any significance to them, surely enough to pique

interest in itself.

The Slayer of Perspective

With really effective art it's often

impossible to separate form and content – and Escher confirms this.

His prints look 'clean', like architects' plans. His preparatory

sketches were often made on graph paper, while his favoured

print-making method was lithography - allowing for greater detail.

The accumulation of this detail reassures the eye, lulls it. This is

the solid, dependable stuff we rely on, that places the floor at our

feet and keeps the ceiling up. It's like a joke told deadpan. It all

looks so plausible you take a while to notice the impossibility, and

even afterwards you still strain to reconcile the two.

'Belvedere' (1958,

above) looks like an instructive diagram, detailed enough in its

workings to be used as a plan. It even contains a diagrammatic map

analogous to its main tower, then a man grasping a model frame

beneath the finished thing. Yet it also has enough incidental detail

to feel like a real place. And it's significant that among this

detail Escher drapes his figures in Renaissance costumes.

There was no particular geographic

reason why perspective was first devised in Italy, Florence did not

contain more vanishing points than other places in the world. It came

about for social reasons, in effect 'bundled in' with other Renaissance developments. Nevertheless the effect was

to create an association. In the same back-of-the-brain way we assume

the Thirties happened in black-and-white, we imagine the Renaissance

was the time spatial depth first opened up. And with his Renaissance

imagery Escher is exploiting this, in a way which wouldn't work had

he used contemporary dress.

We've all become used to Post-Modern

art, which displays the tropes of Modernism while denying them their

meaning. In a similar way Escher is Post-Renaissance, pulling the rug

from under conventions so long taken for granted they seemed a kind

of natural law. “Surely its a bit absurd”, he wrote, “to draw a

few lines and then claim it is a house.” Modernism, inasmuch as it

had a relationship with the Renaissance, was anti-Renaissance,

aiming to supplant it by replacing its pictorial devices, or to look

back to times before it, or quite often both at the same time. But it

didn't subvert it from within in the same way as Escher.

This isn't just true of his warped

perspectives. Staircases and ladders, frequent images, are associated

with hierarchy and with it order. A phrase such as “upstairs

downstairs” suggests everything being in its place in the world.

Escher's impossible staircases screw with this notion.

A similar thing could be said of his

play with levels of reality, such as 'Reptiles'

(1943, above) is which modelling is used to make the reptiles appear

in relief then revert to two dimensions. Or his breaking down of

inside/outside distinctions, such as in 'Print Gallery'

(1956). And yet his warped perspectives seem to have hit home

the hardest. As the most counter-Renaissance bow in his quiver, they

became his twisted Rosebud.

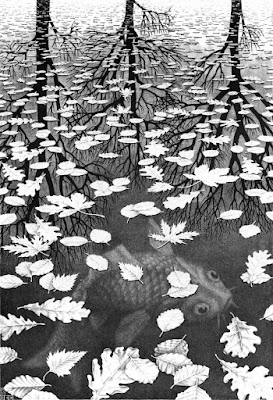

And Escher had one final twist to play

on perspective – he bent it back into shape. There are more

'straight' prints than you'd expect, but when he returns to them late

in his career it still pulls almost the same trick in reverse. In for

example 'Three Worlds' (1956, below), you can take

a while to realise its actually entirely possible. By the end the

presence of genuine perspective and actual levels seems as strange as

their absence. Even normal has stopped looking normal. Who could ask

for anything more than that?

Now the alert

reader has probably spotted what's going to be said next. Escher's

fascination with transformation and systematic distorting of standard

pictorial devices are undermining of the Renaissance. They cause

attention to and thereby question those devices, like a magic trick

being exposed by being done wrong. Yet his attempt to achieve order

and cosmic balance through art, his evoking of some kind of supreme

geometry could not be closer to a Renaissance mindset. Da Vinci for

example often made geometric sketches (compare this to 'Crystal'), and used geometric

forms in his compositions. Escher is the renaissance's successor and

its saboteur. These two things do not fit together. Just like one of

Escher's works, they make less sense the more you look at them. But

the paradox you get when you put them together – that's Escher.

That's who he is. Compellingly impossible.

No comments:

Post a Comment