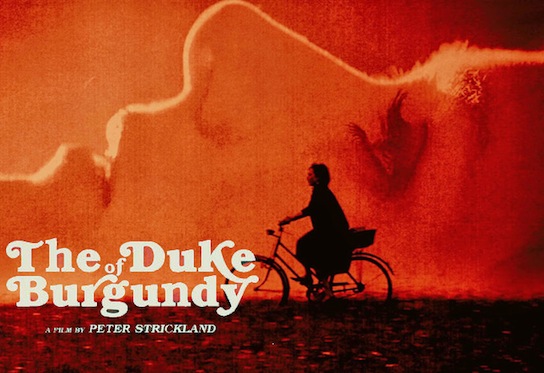

THE

DUKE OF BURGUNDY (WITH LIVE SOUNDTRACK BY CAT'S EYES)

Brighton

Dome, Fri 22nd

May

Part

of the Brighton Festival

This

review does contain some PLOT SPOILERS

Before

the internet showed up and started recording everything, the

fallibility of human memory was almost a creative act. Perhaps you

saw some Seventies pseudo-arty piece of erotica shown on BBC2, and

over the years your memories of it morphed. So hard was it to see

something so ephemeral as a film back then, perhaps you only saw some

stills from it, and resorted to imagining what it might be like. It's

less that your young mind read more into the film than it was

carrying, it's more that the atmosphere of the film and your memories

of it ferment over time, acquire a significance which comes to await

being pinned to something. Like a dream which stays with you, even

though you're never sure why or what it might mean.

Given

this, going back to watch the original film is obviously a mistake

bordering on category error. It won't add anything to a memory that

was only built up subsequently, the film itself can now only undo it

all – like pulling the foundations from a tower. One solution,

perhaps, is to try and remake the film as you remember it. Which is

pretty much what director Peter Strickland is doing here. The

Seventies pastiche credit sequence recalls the one for his previous

film, 'Berberian Sound Studio', but perhaps here

the conceit's enlarged to the whole film.

The

programme quoted him as particularly keen to channel the films of

Jess Franco, which “struck me as being incredibly rich in

atmosphere, intensity and sexual fever”. It notably recycles many

of the tropes of Seventies erotic cinema – the inherent kinkiness

of lesbianism, assumed to overlap with sado-masochism, the

near-hysteric mentality of women – with just enough framing that we

know not to take all this entirely seriously. (The audience

frequently laughed out loud, though even the absurdest moments are

presented deadpan.)

With

it's pointedly indeterminate setting in time and place, it could be

set in the Seventies, or as easily not. It has the same stilted,

distanced feeling of the era, as if the actors are presenting rather

than inhabiting the characters. (Often a side-effect of dubbing,

though English-language films can have much the same effect, such as

'Picnic at Hanging Rock'.) The central characters,

Cynthia and Evelyn, seem to inhabit the same hermetic dream-world,

inside which they are either free to pursue their obsessions, or

constrained to the same. In fact those central characters are pretty

much the only characters, bar a saleswoman, a

distantly-glimpsed neighbour and some public talks. (Where some of

the audience are quite visibly dummies.) Their cloistered world

contains not a single male character.

It's

mentioned in passing that Evelyn owns the big house they live in,

though she seems to have no job to speak of. While you could

speculate over the source of her masochism, the film doesn't seem to

encourage this. Its more presented as something she chooses to

indulge. She even refers to it at one point as “a luxury”.

The

conceit of the film is that Evelyn, ostensibly the masochist of the

relationship, is calling all the shots. And Cynthia becomes wearied

by the way her life has become so scripted. (In quite a literal

sense, she's given cue cards to read like an actor.) Notably,

however, if it is Cynthia who has what Hollywood screenwriters would

call “the arc” the film starts off with Evelyn and effectively

stays with her throughout. Almost every scene, even the ones where

Cynthia breaks down under the burden of bossing, are hers. To quote

Strickland from the programme again: “The most essential aspect of

the film is its dreamy, post-orgasmic flow. One feels as if the film

itself is a spell that Evelyn is under. Being under the spell is what

she's addicted to.”

Sixties

and Seventies culture perhaps became obsessed with the way we live

out roles. (Pinter's 1962 play 'The Lover' has

many of the same elements.) But perhaps it could never quite decide

whether they were liberating or confining. The Situationist writer

Raoul Vaneigem railed against roles as an aspect of modern alienation. (“Roles

are the bloodsuckers of the will to live. They express lived

experience, yet at the same time they reify it. They also offer

consolation for this impoverishment of life by supplying a surrogate,

neurotic gratification.”) While glam rock embraced them about as

fully as can be.

And

the recurrent and title-supplying motif of the moths, prevalent

enough that they get their own section of the credits, exists to

exemplify this. In the film it's both a metamorphosing creature

capable of taking shining flight and a pinned and labelled specimen

on the wall of Cynthia's study. Yet while Cynthia seems happiest

pulling off her wig and peeling her false eyelashes, the film ends

with the roles still in place. Her breakdowns against the script just

become part of the script - another cycle set on repeat. Like the

punishment chest Evelyn insists on being locked in, what makes roles

confining ultimately makes them inescapable.

Cat's

Eyes are Rachel Zeffira and Horrors singer Faris Badwan, not names I

can claim to be familiar with. (Though Badwan was recently controversial for decrying the vote.) It's effective enough. Classical instruments are

marshalled into producing rich and leisurely Europop, wafts of choral

vocals passing like white clouds in the sky, so sweet it almost tips

over into sinister. It matches well enough the spell Evelyn is under.

However,

it's not staggeringly memorable and unlike Goblin's 'Suspiria' seeing it performed live doesn't add

much. Indeed, in one sense the live setting may even distract. For

long periods Strickland uses only ambient sounds – the creak of

cupboards, the click-clack of bicycle wheels. At first, there's a

structural reason. We enter the film with the roleplaying up and

running. Consequently we believe Evelyn may actually be a bullied

maid to Cynthia, so the initial note that's struck must be one of

realism. However, the soundtrack and the ambient sounds then

intersperse through out. Doubtless, the contrast allows each to

enhance the other. But there also seems a way in which Strickland is

actually employing two soundtracks, keeping the ambient sounds

running until we find a musicality in those creaking cupboards.

Yet

when the soundtrack is played live it creates a strange reversal of

the diegetic and non-diegetic, we see the actual strings being struck

but with the 'natural' sound of the cupbaord door being closed

there's only a representation projected onto a wall behind them. It

can weight what should really be a balance.

'Duke

of Burgundy' is perhaps eclipsed by Strickland's two

previous films, 'Katalin Varga' and 'Berberian

Sound Studio'. But it is certainly well worth seeing, if

not necessarily waiting for the soundtrack's next live outing.

LAURIE

ANDERSON: ALL THE ANIMALS

Brighton

Dome, Sunday 24th May

Part of the Brighton Festival

Four

years after her last Brighton festival appearance, Laurie Anderson is back

with an assemblage of her stories about animals. At which point you

may well ask – animals, why them? A clue might come from an early

comment on having read 'Wind in the Willows' as a

child, and the oddity of a six year old reading about “eccentric

gay bachelors”. The point being that Grahame's fully

anthropomorphised animals are really only displaced humans. Whereas

her interest is in things between, with one forepaw in human culture

and a tail flicking back into the animal world. Hence all the tales

of teaching her dog to play keyboards, it going on to headline a lot

of animal rights benefits and all the rest.

Which

may explain both why animals are so popular with children, and why

they are such a staple of fables. And Anderson's conception of

stories is basically fables in more modern dress. Her conceit may

even be that animals and fables become analogies for one another, as

representatives of the indeterminate. In one tale Adam and Eve are

morphed into a yachting couple who moor on an island, and the snake

offers no apples but instead tells Eve stories.

Her

measured, melodiously deadpan delivery leaves you constantly

wrongfooted as to how to take things, as she shifts between anecdote,

surrealist non-sequiturs and philosophical aphorisms. Did she really

do a concert for dogs in Sydney harbour, and did curious whales show

up half-way through? Perhaps, she's done stranger things. But the

literal truth of the stories doesn't seem to matter much, even for

the ones which might actually be true.

The

key image may have come early on. Before the earth was created,

flocks of birds swarmed the air with nowhere to land, endlessly

forming and reforming different shapes. But when one bird dies they

have nowhere to bury him, so his daughter inserts him in the back of

her head. Then began memory. Memory and the earth thereby become

conflated. Each gives you a reference point, they're ordering

devices. But ordering devices associated with myth's classic Fall

moment – awareness of death.

And

Anderson's accumulated stories become like the murmurations of those

birds. It's an image remarkably similar to the one in 'Landfall', of her belongings floating in her

flooded studio after Hurricane Sandy. As the show moves on things

don't develop so much as accrue, images and themes sparking off one

another. The earth's gravity never quite takes control. Like the

daughter bird, there's no path laid our for us. The show's not about

dispelling nuggets of feelgood wisdom or giving you new ideas about

the world. It's more like getting a personal trainer for your

imagination, making you more alert to associations, sharpening your

antennae.

Not

unrelatedly absence was also a key theme. There's lists of all the

animals who have existed over time but are now gone, there's the

Hebrew alphabet kicking off with a silent letter to represent all

that can't be said. (I have no idea whether this was something she

made up or not!) It suggests these epigrammatic tales are themselves

incomplete. They're there largely to hint at larger things, even if

its up to us what those larger things might be.

Like

the daughter bird, the show is so reliant on us doing so much of the

work the glass of water can feel half-empty as easily as half-full.

This show worked better for me than her previous Festival appearance.

Perhaps I was more keyed in to what to expect, or perhaps the

experience is so subjective it may simply be down to what mood you're

in on the night.

Something

she didn't do at all in Brighton, from Buenos Aires...

Coming soon! More of this sort of thing...

No comments:

Post a Comment