Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

The State of Things Back Then

Still lives, we’re soon told, had traditionally been pushed to the bottom in the hierarchy of the arts. Laid out in rank order, these were - Historical scenes, Portraiture, Genre painting, Landscapes and (as you may have guessed) Still Life. That slightly oddly named “genre painting” meant everyday scenes. So what this came down to was Important People Doing Important Things, Important People Looking Important, Unimportant People (Possibly Doing Things), No People But Big and Not People Not Even Big. You can see the thinking. They weren’t educational or morally instructive, they were just of things.

So what was any self-respecting Modernist to do? Upend the hierarchy, of course. Pull the bottom level out to collapse the thing, like a Jenga tower.

Yet in one way this can seem counter-intuitive, for we think of Modernism as being about creating newly dynamic art for a newly dynamic age. But it also, in general not just in art, took against the grand historical sweep and took to the close focus. The most clear-cut example must be Joyce’s ’Ulysses’ (1920), reworking the Odyssey into a single day of a quite regular life. At the time physics turned its gaze from stars and planets to particles.

Perhaps the ranking wasn’t all that surprising. We are egocentric creatures who are primed to see reflections of ourselves, and in no place less than our art. In fact, it can sometimes feel like we invented the thing just so we could make ourselves a flattering mirror. And as always, taking something out can create its own form of presence. When not sated our innate egoism doesn’t go away but into overdrive. Denied the desired sight of human beings we carry on looking for it anyway. And this can be put to use, in different ways…

How often, for example, have you seen a scene such as the one above? Solid-looking furniture before an open log fire, accumulated and exotic objects, clearly a mansion of some kind. But instead of the tweed-wearing Lord, in ’Amaryllis’ (1951) Stanley Spencer has placed a plant. (The plant of the title, in fact.) Pushing itself front and centre, running almost the full length of the frame, occupying the space art normally reserves for humans, it grabs at your attention. While the plant has more than one flower, one is firmly turned to face us, accentuating the anthropomorphism. You’re soon ascribing some form of sentience to it, just from context and positioning. (‘Day Of The Triffids’ was published the same year. Coincidence? Yes, probably.)

Whereas William Nicholson’s ’The Silver Casket and The Red Leather Box’ (1920, above) hints at a helmeted human figure. Intentional or otherwise, you cannot not see it there. Pushing this implication further is the silhouette of, presumably, the artist reflected in the casket.

But there’s as many approaches to still lives as there are in any other genre. Edward Wadsworth’s ’Bright Intervals’ (1928, above) places together a clutch of objects. Now objects should be simple, functional things, instruments for our use. And we immediately see they’re all related to the sea, and are painted in a vivid but limited palette, almost like a striped flag. (It was painted in tempura.) The title emphasises both these at once.

So its a work which should surely be easy to parse, yet somehow its not. Its like a sentence made up of words you know, which seems to follow grammatical order, but gives up no sense. I suspect its concerned with the distinction between the ideal world, represented by the objects in the foreground and the real word beyond, represented by the sea. The curve of the blueprints is echoed by the prow of the ship. It has the deep blue we associate to the sea, which is here rendered green. A barrier (a wall, a window?) lies between the two. The territory never matches the map.

Yet of course the whole point here is that we don’t understand, that these simple objects elude us. How did such a thing come about?

Prior to Modernism, many works were tableaus. They were painted via models holding stilted poses for long periods, while the artist debilitated and laboured. And for the most part they looked it. Their purpose being to convey a point (the Nativity, victory in a battle and so on), naturalism wasn’t strived for. So, while ostensibly of people, they were stiff and rigid. Art stilled life. Still lifes such as this essentially reverse things, painting inanimate objects as an arrangement of elements, but in a manner which feels elusive.

But there’s another, more oblique, influence. Edwaert Collier’s work above is titled ’Vanitas Still Life’ (1694) and Vanitas was often used as a name for this Dutch genre. “They sought,” the show says, “to convey the transience of life through arrangements of inanimate symbolic objects.”

(We’re also told that from the Seventeenth century these were imported. I confess to not being sure how we’re supposed to take this. This is a show devoted to, in its own words, “Modern and Contemporary British artists”. Had the snobbery over still lives been stopped a good couple of centuries before Modernism began? Or were they considered exceptions to the rule, before Modernism came along to take them up? But no matter. Let’s focus on what they did, and how they were received.)

The stillness of them feels foregrounded, creating an eerie calm. It’s like breaking into the room of a person long dead, their possessions lying as they are. We become aware what has happened to them will come to us. We are transient, our things will outlast us.

At this point I’ll take a guess. My guess is that this was not how they were received, at least not at this point, the early days of British Modernism. Some of the symbols used are effectively universal, the widely repeated skull to stand for death scarcely needing much interpretation. But many were specific to another time and place, a shared understanding gone. (In the way that one work here uses roast beef to represent England.) They arrived to British Modernists inscrutable and mysterious, devoid of a code book. Which of course made them enticing. So why not do the same to someone else?

And this leads to works such as Mark Gertler’s ’The Dutch Doll’ (1926, above) which possess a sinister, suggested animism, lurking near the surface without emerging. If you looked away and back, would things have moved? As the show says, ‘Still Life’ is “a contradictory name”, why not play that up?

The doll, placed centre where the human figure would normally go, is a clear enough source of this. As children we imbue dolls with life, a habit we never absolutely break from. But the picture is full of such suggestions. The flowers are of course painted, but on their vase is a painting of flowers. The playing cards also perform a picture-within-a-picture function. While the plant to the left seems to be composed of moving tendrils, enhanced by the sharp painting style. And the red curtain to the right suggests we’re looking at a stage, which makes everything on it props but also actors.

Outside this show, elsewhere in the gallery, Claire Rudland is quoted as saying: “There is more than what we see, there is something other.” She’s describing her own work. Yet it’s as fitting for this and many other works in the show.

Ask Not What, Ask Instead How

Objects, then, can be both present and elusive. But there’s also other approaches. One is to paint not just still lives but the same few objects over and over. With familiarity they fade from your attention, which instead falls on *how* they’re depicted. Which is perhaps Modernism in essence. Questions of how can never be disentangled from questions of why. (Cubism played a similar trick.) And from there, you’re free to take any route you want.

In ’The Cup And Saucer’ (1915, above), Harold Gillman homes in and fills the surround, so the title objects contain almost the only white in the composition. But rather than give them a smooth coat as would befit china, the paint is crusted thickly and in varying shades. Rather than something dull and solid, they seem to radiate and shimmer before you. (Who could have guessed a cup and saucer could be made into something so vivid?)

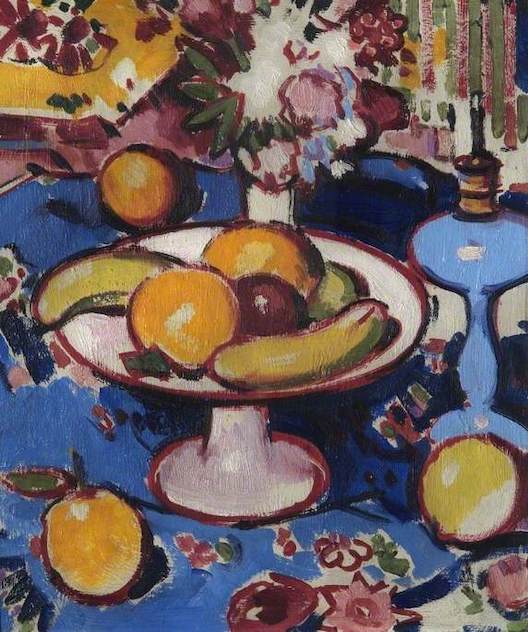

John Duncan Fergusson’s *’The Blue Lamp’* (1920, above) bears some compositional similarity - close-cropped, and centred around a white object. But its made up of bright, solid blocks of colour, held within thick red outlines, to the degree it could almost be a screenprint. The elements act almost like notes in a composition. In style, the two works are worlds apart.

While Winnifred Gill’s ‘Still Life With Glass Jar and Silver Box’ (1914) keeps the heavy outlines, then makes the colours beneath them shift around and recur. Gunmetal grey seems reserved for shadows, but the two shades of brown dart around the composition. (The restrictions of the First World War already in place, Gill used a tea chest lid for a canvas.)

The Path To Abstraction Is Paved By Things

As artists were mostly interested in cups or fruit not in their own right but for their formal qualities, this meant still lifes played a prominent role in the path to abstraction. You can see the timeline over several Ben Nicholson works in the show. The first step is to make them into symbols. With ’Striped Jug and Flowers’ (1928, above) you don’t imagine grasping that jug by the handle. It’s an image of a jug, flattened into a representation, abstracted from any environment. Even as the flowers seem more three-dimensional.

Then eighteen years later, the almost fully abstract ’Still Life, Cerulean’ (1946, above) retains the lines of the jug handle at upper right.

…all of which may be true. But you cannot help feel the show overplay this a little, in order to fit it to their theme. The *’Expressionists’* show at the Tate (currently still running) demonstrates the same thing happening with landscape art. (Yes, one whole rung up the Academy’s hierarchy of genres!) At this time, all roads non-figurative led to abstraction - and sometimes figurative too.

Things During Wartime

Remember how we came in? The still lifes which inspired all this conveyed the transience of life by depicting the relative permanence of things? And how British Modernists instead created works which were dazzling and brilliant?

Then it seems something came along to burst this bubble. Around the year 1939, should you need a clue. And so we arrive at a room called the jolly 'Death, Decay and Post-War Austerity’. Skulls were back in a big way.

One of the best works is Edward Burra’s ’Still Life With Teeth’ (1946, above), precisely because it eschews such standard images and instead manages to make a fruit bowl menacing. The objects aren’t just pushed to the foreground but monstrously oversized. And other apparently domestic objects are also infused with lurking threat, the show talks of how the cutlery is imbued with “the sinister allure of weapons”.

The teeth and shoe are the only signs of human life, save a tiny figure fleeing the scene, long-shadowed in a de Chirico boulevard. Our misadventures have borne these monstrous fruits, which now dominate and push their creators from the frame. This is life thrown out of balance, as hallucinogenic as Dali yet more intimate. (This would be a good time to remember that the Pallant House once had a great show dedicated to Burra.)

Things - Not What They Used To Be

Then, after that final twist, things lost their lustre. Modernism had essentially won its battles, nobody was really talking about the hierarchy of genres any more, and so still lifes had little use. But it's natural enough. Nothing is useful forever, not even things.

Alas the show, which has up to now been enthralling, doesn’t work out this is the time to stop. Instead it progresses into Pop Art. Which does something entirely different. The representation of things, which had once been central, was no longer a question. Now the closer you could make the representation to the things themselves, the better. In a time of mass production, make art which looked like product. Airbrush. Or screnprint. Collage. Or just take the objects themselves and use them.

And what does this change? It changes everything! Pop Art appropriates, takes and recombines. (This is particularly daft when the Pallant House has already had a Pop Art show, which laid out all of this.)

Though one work which both belongs in context and is worth seeing is John Bratby’s (rather splendidly named) ’Still life With Chip Fryer’ (1954, above). As translucent doesn’t work well in painting, you can by tradition use white for glass. Here Bratby uses pure white not just for glasses and bottles but a whole bunch of objects, including a sieve. Others are bright blue.

Products include brand names, which might seem classic Pop Art. But all this is amassed together onto a drab brown table with drab wooden chairs in a drab room of bare floorboards. It looks like a collision, a clash of reality systems, a foreign invasion, almost like the Science Fiction device of sticking alien spaceships in Trafalgar Square. Its a fifties were the Forties and Sixties were struggling for control. (Regular reminder - great artists weren’t always great people. Bratby was an abuser.)

But let’s end there before we run into Rachel Whiteread. If this show loses its way later on, art did too. So let’s look to its successes. Early Modernists had a slightly paradoxical relationship to the still life. They saw a life in things which loftier-minded artists had missed. While at the same time they saw a nailed-down subject which allowed them to focus on questions of how. The result is works on what might seem the dryest and dullest of subjects, which are full of life.