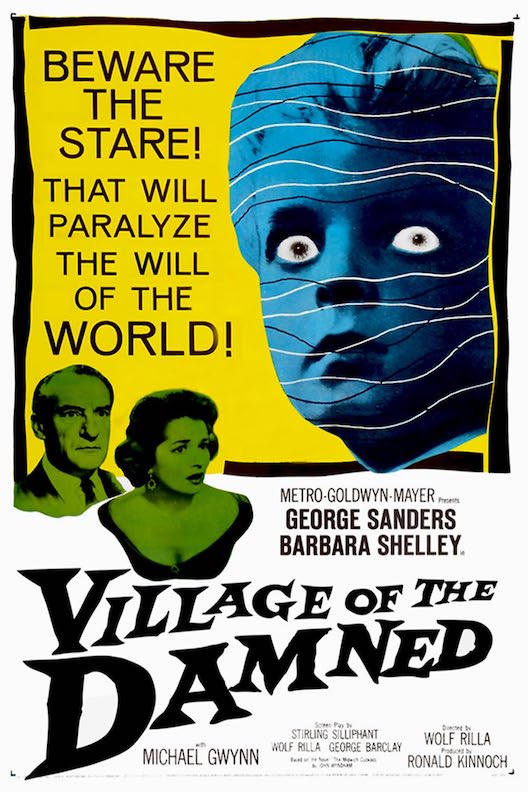

“Here is a picture. Someone is - other. Not one of the people.”

Seeing The Picture

William Golding always cited his second novel, ’The Inheritors’, (1955) as his favourite, even it it never achieved the recognition awarded its predecessor ’Lord Of the Flies’. It’s centred on the people, a pre-human group from stone age times. And tells of their encounter with the new people, modern humans. Now surely such a thing cannot belong in a series on pariah elites, alongside van Vogt potboilers? Don’t be so fast…

Its distinction is to be written not just from the perspective of the people, but in an approximation of the language they would have used. Or, as Golding’s daughter Judy more accurately put it: “my father uses our language to show the lives of people who don’t really have it.” And accordingly every sentence, whether prose or dialogue, deepens our understanding of the people.

The language is therefore simple and direct, at points almost reading like stage directions. But still with something evocative to it:

“The red creature turned to the right and trotted slowly towards the far end of the terrace. Water was cascading down the rocks beyond the terrace from the melting ice in the mountains. The river was high and flat and drowned the edge of the terrace.”

And they speak so simply and directly, of course, because they lead a simple and direct life, chiefly based around foraging.

“Life was fulfilled, there was no need to look farther for food, to-morrow was secure and the day after that was so remote that no one would bother to think of it.”

Their perspective is in many ways child-like, including ascribing sentience to objects if they’re seen moving.

“The water was not awake like the river or the fall but asleep, spreading there to the river and waking up.”

But the best-known aspect of this is their communicating via ‘pictures’, as in their phrase “I see/ do not see that picture.” This suggests two things, that they have not ventured far into abstract thought, and that idea and memory are not separated. Stuck with a problem they assume it must have been encountered before, so the answer will lie in the past. While “this is a new thing” is said like a curse. Though we casually use phrases such as “I see what you mean”, there is something transportive about this. I first heard it decades ago, in a TV documentary on Golding, and found it has remained in my head ever since.

At the same time, their other senses are so acute they are described as having their own autonomy. For example, Lok’s feet are “clever” in dodging obstacles as he runs, while at another point “Lok’s ears spoke to Lok” but he doesn’t hear them as he’s asleep. They follow a trail less by visual clues than by scent, and can become so locked into the task their other senses barely register with them.

And speaking of Lok… His name is literally the first word of the novel and we stay with him right up until the penultimate chapter. The slowest-witted of the adult people, often in a state of “obedient dumbness”, he therefore becomes an unreliable narrator. Events are described through him faithfully but not always comprehendingly. We’re often required to read past his words to understand what’s actually going on. At points, others in the group are required to explain to him, and thereby us, what’s really happening.

But also, what he doesn’t perceive is as important as what he does. For example, when he first sees the new people he assumes they have “bone faces”. Which turns out to be their skin, but in the hitherto unfamiliar shade of white.

He hears the new people’s chatter, of course incomprehensible to him. But he continues to assume they can understand him. And he’s similarly unable to comprehend their hostility, like a schoolboy unable to take in that he’s being bullied, let alone do something about it. When they fire an arrow at him, he first assumes they must be sending him a gift.

But let’s ask an awkward question. If written through him so comprehensively, why isn’t it written as if by him, in the first person? Instead the novel opens more cinematically, the members of the tribe as brought into view one by one as they enter a setting. And at this point, emotions are given visual indicators. (“The grin faded and his mouth opened till the lower lip hung down.”) Though internal states do creep in as it progresses. (“Quite suddenly he was swept up by a tide of happiness and exultation.”)

The answer is this novel can’t be too centred on an individual, because it’s about a collective. Lok would not have seen himself as a discrete being, but as a part of the people. In one passage, heading on an errand, he looks back on the rest of the group from a vantage point where he’s no longer visible to them:

“All at once Lok was frightened because she had not seen him. The old woman knew so much; yet she had not seen him. He was cut off and no longer one of the people; as though his communion with the other had changed him. He was different from them and they could not see him. He had no words to formulate these thoughts but he felt his difference and invisibility as a cold wind that blew on his skin.”

And this is not in reaction to being lost or exiled, just temporarily separate. Later when he first sees the others he recoils into the comforting sense of being one of the people:

“They came in, closer and closer, not as they would come into the overhang, recognising home and being free of the whole space; they drove in until they were being joined to him, body to body. They shared a body as they shared a picture. Lok was safe.”

Then, right at the end of the novel, one section switches over to impersonal narration. For the first time we see Lok rather than see through him. (“A strange creature, smallish and bowed.”) At this point he’s the only one of his people left, bar a stolen baby. And, as he cannot exist alone, he’s effectively already dead. He’s described objectively because he’s become an object. When the root they’ve made the totem of their deity, Oa, is described simply as a tree root its heartbreaking, but heartbreaking precisely because its an unarguable truth.

There’s a section in Wyndham’s ’Day Of the Triffids’ (1951) which parallels this:

“The prisoner and the cenobite are aware that the herd exists beyond their exile; they are an aspect of it. But when the herd no longer exists there is, for the herd creature, no longer entity. He is a part of no whole: a freak without a place…no more than the twitch in the limb of a corpse.”

And they speak so simply and directly, of course, because they lead a simple and direct life, chiefly based around foraging.

“Life was fulfilled, there was no need to look farther for food, to-morrow was secure and the day after that was so remote that no one would bother to think of it.”

Their perspective is in many ways child-like, including ascribing sentience to objects if they’re seen moving.

“The water was not awake like the river or the fall but asleep, spreading there to the river and waking up.”

But the best-known aspect of this is their communicating via ‘pictures’, as in their phrase “I see/ do not see that picture.” This suggests two things, that they have not ventured far into abstract thought, and that idea and memory are not separated. Stuck with a problem they assume it must have been encountered before, so the answer will lie in the past. While “this is a new thing” is said like a curse. Though we casually use phrases such as “I see what you mean”, there is something transportive about this. I first heard it decades ago, in a TV documentary on Golding, and found it has remained in my head ever since.

At the same time, their other senses are so acute they are described as having their own autonomy. For example, Lok’s feet are “clever” in dodging obstacles as he runs, while at another point “Lok’s ears spoke to Lok” but he doesn’t hear them as he’s asleep. They follow a trail less by visual clues than by scent, and can become so locked into the task their other senses barely register with them.

And speaking of Lok… His name is literally the first word of the novel and we stay with him right up until the penultimate chapter. The slowest-witted of the adult people, often in a state of “obedient dumbness”, he therefore becomes an unreliable narrator. Events are described through him faithfully but not always comprehendingly. We’re often required to read past his words to understand what’s actually going on. At points, others in the group are required to explain to him, and thereby us, what’s really happening.

But also, what he doesn’t perceive is as important as what he does. For example, when he first sees the new people he assumes they have “bone faces”. Which turns out to be their skin, but in the hitherto unfamiliar shade of white.

He hears the new people’s chatter, of course incomprehensible to him. But he continues to assume they can understand him. And he’s similarly unable to comprehend their hostility, like a schoolboy unable to take in that he’s being bullied, let alone do something about it. When they fire an arrow at him, he first assumes they must be sending him a gift.

But let’s ask an awkward question. If written through him so comprehensively, why isn’t it written as if by him, in the first person? Instead the novel opens more cinematically, the members of the tribe as brought into view one by one as they enter a setting. And at this point, emotions are given visual indicators. (“The grin faded and his mouth opened till the lower lip hung down.”) Though internal states do creep in as it progresses. (“Quite suddenly he was swept up by a tide of happiness and exultation.”)

The answer is this novel can’t be too centred on an individual, because it’s about a collective. Lok would not have seen himself as a discrete being, but as a part of the people. In one passage, heading on an errand, he looks back on the rest of the group from a vantage point where he’s no longer visible to them:

“All at once Lok was frightened because she had not seen him. The old woman knew so much; yet she had not seen him. He was cut off and no longer one of the people; as though his communion with the other had changed him. He was different from them and they could not see him. He had no words to formulate these thoughts but he felt his difference and invisibility as a cold wind that blew on his skin.”

And this is not in reaction to being lost or exiled, just temporarily separate. Later when he first sees the others he recoils into the comforting sense of being one of the people:

“They came in, closer and closer, not as they would come into the overhang, recognising home and being free of the whole space; they drove in until they were being joined to him, body to body. They shared a body as they shared a picture. Lok was safe.”

Then, right at the end of the novel, one section switches over to impersonal narration. For the first time we see Lok rather than see through him. (“A strange creature, smallish and bowed.”) At this point he’s the only one of his people left, bar a stolen baby. And, as he cannot exist alone, he’s effectively already dead. He’s described objectively because he’s become an object. When the root they’ve made the totem of their deity, Oa, is described simply as a tree root its heartbreaking, but heartbreaking precisely because its an unarguable truth.

There’s a section in Wyndham’s ’Day Of the Triffids’ (1951) which parallels this:

“The prisoner and the cenobite are aware that the herd exists beyond their exile; they are an aspect of it. But when the herd no longer exists there is, for the herd creature, no longer entity. He is a part of no whole: a freak without a place…no more than the twitch in the limb of a corpse.”

This communion also manifests in a profound empathy. When the old man of the group falls in the freezing river “the group of people crouched round Mal and shared his shivers.” They’re doing more than warming him with their body heat. They see no particular distinction from if they had fallen into the river. ‘An injury to one is an injury to all’ isn’t a credo to aspire to, it’s a functional feature of their lives.

Their ‘telepathy’ must be seen as stemming from here. Though that’s the term commonly used by commentators, and it would best suit this series, I’m not sure it’s quite right. Certainly not in the sense of a phoneless phone call. There’s a sense shared between them which is a combination of suggestibility and empathy. They share the same experiences which frame their thought, so share much the same thought, so can project their ‘pictures’ between brows. And the suggestion can travel because it is non-verbal, akin to the way a simple phrase can get communicated across a bad connection.

And what’s crucial here is that the people do not lose something nebulous such as ‘innocence’, even if that’s how the book is often described. They lose tangible things, a group bond and a perspective on the world perhaps beyond what we can imagine.

None of this is to suggest they lack individuality, or fail to see any sense of it in each other. Fa is clearly more acute than Lok. She not only works out before him the threat the new people pose, she hides from him her own realisation that they’ve killed a child. It’s that they don’t see the significance in individuality that we do.

The people are in an interchange between tribe and family group, from grandparents/elders down to infants. This was perhaps partly to make the cast list manageable, and partly to make them more sympathetic to Fifties audiences. (Golding’s daughter has suggested they were based on his own family.) Lineage is an unimportant question to them, subservient to if not overridden by the sense they are the people. Inferred from his actions, Liku must be Lok’s child, but he never refers to her as such.

Are We the Baddies?

How accurate is any of this? Golding seems to have told different tales over the years about the level of research he did. But we know he wrote the book quickly, and in the covering note originally sent to his publisher he confessed to doing little. Most likely, he simply relied on the knowledge he’d already absorbed and concentrated on writing.

I’ve done no great deal of research either, but some seems solid enough. Contrary to a common error, the people are nomadic rather than itinerant. As the novel opens they’re travelling from their winter to their summer quarters, and on reaching there act like coming home. It’s explained in some detail how they’re able to harvest fire but not make it, so carefully carry embers around with them embedded in clay.

We also discover they see it as sinful to hunt and kill, but acceptable to snatch already-dead prey from predators. Yet not only do we now know Neanderthals hunted, I’d not sure this mode of subsistence has existed anywhere. (Please correct me in the comments if I’m wrong!)

In Golding’s day it was still accepted that Neanderthals lacked the culture and communication skills of the Cro-Magnons, and so were if not eliminated then out-competed by their more innovative cousins. The discoveries of subsequent years have not exactly been kind to these easy notions. It would seem truer to say they did things differently, rather than not at all.

But then again, was this written as an exercise in scholarly accuracy? I do not see that picture. The Bible story of Cain slaying Abel is a kind of secondary Fall myth, where man turned against man and so became marked forever. It’s often regarded now as a mythologised retelling of hunting versus farming. This could be seen the same way, save that the stages represented are hunting versus gathering. We are better off reading it as a myth or fable than as a history of pre-history.

So it doesn’t make much literal sense that Lok looks uncomprehendingly upon the new people bonking, when he’s almost certainly a father himself. Or that the new people are white, when as more recent arrivals from Africa they’d more likely have been darker skinned than the natives. But this is a work of fiction, which affects us via symbols. Lok looks upon the new people as a child would upon adults. And the new people need to remind us of us, at a time when Golding’s readers would have been almost entirely white. So white they are.

How many times have you seen this trope in films? An exploratory mission is crossing a landscape, which seems devoid of life but turns out to contain hostile natives. The camera pans to their narrowed eyes, peering sinisterly from behind foliage. Golding reverses this, keeping the Cro-Magnons at a distance for almost the first half of the book. It progresses almost schematically, we see them first as distant murky shapes, very slowly getting closer to them. A whole chapter is given over to Lok and Fa observing their camp from hiding, literally reversing the standard perspective.

And their lurking at the periphery of the people’s vision is highly effective dramatically. This book is as compelling a read as anything else in this series, despite the relative lack of gaudy pulp covers, rocket ships and missile strikes.

The new people are compared to “when the fire flew away and ate up all the trees,” a collective trauma. But everyone instinctively runs from a fire, while they have something compelling about them. At one point Lok finds a flagon of their beer. Fa warns him off it, but he feels compelled to drink. “It was a bee-water, smelling of honey and wax and decay, it drew toward and repelled, it frightened and excited like the people themselves.” Soon, intoxicated by it, he cries out he now is the new people. It’s like Pandora’s Box as a liquid.

But of course all this raises the further question - why would we need such a fall myth be told? Despite what almost every writer in this series has assumed, evolution is not about linear progress but branching. Following one branch precludes the others, but that doesn’t make one branch objectively better.

In which case, why does this persist? Why, if that ’out-competed’ theory about the Neanderthals was so baseless, was it so widespread for so long? Of course, because people wanted it to be true. A capitalist society will forever try to divide us up into two groups, the entrepreneurs and forward thinkers versus the passive non-adaptors, who need to be dragged along the march of progress. (As one example, in Britain the Tories currently favour the term “the blob” for any and all of their adversaries, with its connotations of an inert blocking mass.) It seems to make sense to us, and so we project it back through time.

We serve ourselves up a fait accompli. The Cro-Magnons must surely have been innovators because they survived to become us. The Neanderthals cannot have been, because they died out. It’s a cross between doing down the neighbours and dissing the dead, in order to big ourselves up. And, in so doing, bestowing upon us an abundance of the things we regard as important.

So stone age dramas most commonly become a version of the Robinson Crusoe myth. They set brutishness up against an embryonic form of civilisation, smarts trumping strength, as if this was the era we struggled to rid ourselves of alternately our childhood or our ‘animal-ness’. (With the two often lazily elided together.)

As Susan Mandala has said: “Scientific and fictional accounts of human evolution share the same basic structure and elements as fairy tales, with humans emerging as transcendent after overcoming a series of obstacles.”

Meanwhile, over the other side of the fence, I have sometimes been treated to a hippie theory that spiritual, creative people (such as the Irish) were descended from Neanderthals and grasping, possessive types (aka the English) from Cro-Magnons. You may already be able to guess how accurate that is. As so often, the supposedly ‘alternative’ theory retains the mainstream concepts while somehow trying to invert the value system between them.

Golding is not, of course, as foolish as that. The people don’t lead some Edenic life, but one periodically plagued by hunger. Fa, the brains of the outfit, is firmly told to stop having ideas because girls don’t do that sort of thing. But like the hippies he retains the concepts. Except in his case he asks what downside those advances might have brought with them, and devises a scenario which best demonstrates his concerns.

The people live as part of the landscape. Lok’s reaction to returning to their summer camp is: “The river had not gone away either or the mountains. The overhang had waited for them. Everything had waited for them; Oa had waited for them. Even now she was pushing up the spikes of the bulbs, fattening the grubs, reeking the smells out of the earth, bulging the fat buds out of every crevice and bough.”

While the new people impose themselves upon the landscape, chopping down trees, broadening paths to carry their canoes. Tools become cursed objects, functionally useful but separating their wielder from the world, imposing upon them a utilitarian mindset. What makes them more civilised also makes them more savage. (Disclaimer: the people will use rocks and sticks as tools, in an impromptu manner, but do little to fashion them and don’t hang on to them after their immediate function is served. The only exception seems to be the thorn bushes they hold onto as defensive weapons.)

Ellethinks saw the distinctive thing about the new people as their use of abstract language, focusing on a scene where their onset stimulates linguistic concepts even in Lok. (And, though she doesn’t say so, to a greater degree in the smarter Fa, who’s able to devise a pincer assault on the new people.) This is a valuable point, but in itself insufficient. There must have been a means by which the new people were able to develop this enhanced language, it can’t by itself have instigated their difference from the people. It must be effect, not cause.

The final chapter switches to follow Tuami, one of the new people. They have taken the people’s baby. (Though I don’t think it was known then that Cro-Magnons and Neanderthals interbred.) He whittles at a knife he is making, whose handle will be half of the baby and half one of his own people. When it’s finished he intends to kill the group leader and usurp his role. The last line is “he could not see if the line of darkness had an ending.”

The Yesterday People

So to return to the initial question, does this belong? There’s one obvious similarity to other Pariah Elite novels. If in varying degrees, they try to capture in prose how the world would look to a differently working mind. But that’s a partial likeness at best. And Golding’s pessimism seems entirely at odds with the teleological optimism of something like ’The Tomorrow People’.

And yet for all that they’re remarkably similar. Not just in their nascent form of telepathy, but their collective identity (that shared use of “people” is scarcely a co-incidence) which is enough of an erosion of the self/other distinction to turn them from violence. Andrew Rilstone smartly said that for all their jaunting and telekinesis “the Tomorrow People's main power is that they are nice.”

’The Tomorrow People’ portrays us in a state of becoming, for the nice will inherit the earth. While the people are effectively the Yesterday People, the last of the nice. But Golding’s pessimism isn’t absolute. He doesn’t say the line of darkness had no ending, only that Tuami could not at that point see it. The knife he makes is dualistic, and Neanderthal DNA still lies within us. We may see that picture yet.