”Blessed is the norm! Watch thou for the mutant!”

Deviation and Progress

Brian Aldiss, not always Wyndham’s greatest fan, described ’The Chrysalids’ (1955) as his best book. About which he may well be right. But in a more unarguable point, it’s about a pariah elite possessed of mutant powers. So it fits into our series like a six-fingered glove. (See here for list so far.)

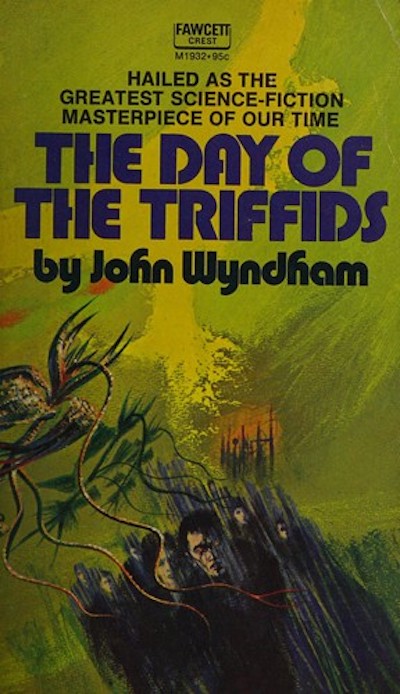

Then on the other hand... The original Penguin version of his breakthrough novel, ’Day of the Triffids’, had described it as “a modified version of what is unhappily known as ‘science fiction’,” his earlier career in American pulps politely elided over. For his writings were now aimed squarely at the regular reader. Which means what has been our standard model, that mutant powers act as a metaphor to big up science fiction fans’ self-image, no longer applies.

But that other hand may be six-fingered too. It only needs a little tweaking…

As we saw last time, ’Day of the Triffids’ essentially came from the culture of the Forties, even if it was published early in the next decade. But much of what makes a good popular writer is the ability to act as an antennae for the zeitgeizt. And this mid-Fifties book, conversely, looked forwards. If van Vogt’s credo was in essence “fans are slans” (even if he didn’t devise that phrase himself), Wyndham’s is “kids become butterflies, adults just stay grubs”.

The conceit is similar enough to ‘The Tomorrow People’ for two different covers to use the same splayed-hand image as it had in its opening credits. But when that specified puberty as the point your powers manifested, here its a more general youth. And that wider range makes it a coming-of-age story. Powers increase with age and, significantly, its the youngest who is the most powerful. While even the older sister of protagonist David lacks them.

In a later introduction, M. John Harrison commented on its appeal to the post-war generation: “They had more in common with each other than with their parents. Their social expectations were raised… they were in possession of a new language… the generation gap was opening up.”

(Wyndham had gone to the ‘progressive’ public school Bedales, which a couple of generations later would be pretty much the type of background the leaders of the Sixties counter-culture came from.)

This being post-nuclear world where only the margins remain inhabitable it’s set in Labrador, Northern Canada. Or a version of it. Much is made of this being Wyndham’s only work to have a fantasy setting. But what that really means is that it’s not set in contemporary South-East England. If strictly speaking it has no real-world equivalent it’s a setting we quickly recognise from elsewhere. It’s a Western, just one where the past-the-border badlands is populated by mutants rather than outlaws. Strictly speaking, it’s Western crossed with a pioneer town of devout Puritans as in ’The Crucible’ (1953). But the two mingle easily enough, especially to us British readers.

Labrador is more Kanas than Oz. And the abnormal, after all, only has meaning in relation to the normal, the mutation to the standard.

Now, you may be about to say that Science Fiction is almost always relabelled Westerns. But this isn’t Flash Gordon, shootouts against a more exotic backdrop. It’s very much set in a material world where people till their own soil, fix their own carts, and hunt with bows and arrows (plus the occasional primitive gun).

And this makes the introduction of telepathy juxtapositional, as strange an interruption to this world as it would be to ours. The adults are obsessed with rooting out ‘deviation’ (as they call mutation) but spend much of the novel looking for it in the wrong place, outer rather than inner, getting all het up over an extra toe. (The novel is somewhat fuzzy over when the young folk first recognise their powers will count as deviation.)

Added to which, telepathy is the only one of the Tomorrow People’s three T’s to be incorporated. And here it means just mind-talk, no mental control or powers of suggestion. There’s a narrowing of unbelievable things, until there’s only one asking to be believed. Which is itself subject to material constraints, a point reiterated even if they’re hazily defined.

”The Shortcomings Of Words"

At the same time telepathy isn’t just phone calls without phones. Telepathy is qualitatively different, a higher form of communication…

“Even some of the things he did not understand properly himself became clearer when we all thought about them.”

Unlike all those other Ts, telepathy only works as a group power. Telepaths can only contact other telepaths. And this ‘thinking-together’ is about the young folk’s ability to immediately put their heads together, similar to Brian Eno’s dictum “everyone is smarter than anyone.”

But it’s more than that…

“I don’t suppose ‘normals’, who can never share their thoughts, can understand how we are so much more part of one another. What comprehension can they have..? Wwe don’t have to flounder among the shortcomings of words; it is difficult for us to falsify or pretend a thought even if we want to: on the other hand, it is almost impossible for us to misunderstand one another.”

We’re told that pre-apocalypse people "were shut off by different languages and different beliefs”, suggesting telepathy is a universal language that will by its nature overcome such divisions. True, there’s limits to this. We’re also told no-one can know David’s love interest Rosalind as well as him, even the other telepaths. But its simultaneously suggests that telepathy enables them to achieve a higher form of love, much as van Vogt did in ’Slan’.

Wyndham’s ‘big three’ novels are surely this, ’Triffids’ and (coming up) 'The Midwich Cuckoos’. Yet while the others have been adapted multiple times, this has only had a 1981 radio version. And surely a main reason is the difficulty of visualising this ‘thinking-together’.

As with ‘The X-Men’, their powers are essentially given a double explanation. Ostensibly they’re mutations due to post-nuclear radiation. But it would be hard not to see teleological evolution’s hand here too. And, as with the X-Men, these two explanations seem rather shoehorned together. In something closer to a ‘serious novel’ than a four-colour comic, where we might expect better.

But they perform different tasks. The first is diegetic and plot-functional, to give the adults a reason to fear the children. The second is more symbolic, closer to a metaphor even within the story. To quote Harrison again: “Telepathy in fiction is often a metaphor for communication, for empathy, for an open style of human relationship.”

For ‘thinking-together’ is set against a society predicated on conformity. (“The more stupid they are, the more like everyone else they think everyone ought to be. And once they get afraid they become cruel and want to hurt people who are different.”) Labrador becomes a caricature of the ordered, rule-bound world of the Fifties, of strictly enforced dress codes and table manners, where the over-riding requirement is to fit in.

And further to Harrison telepathy is also something of a metaphor for the reading experience, symbols placed in your head across a distance, showing you things as others see them, accessing what can feel like a higher level of space. And it can feel that others who don’t seem to get the same experience from reading as we do are in some way missing a sense, are mere norms.

”Condemned to negatives”

As with ’Slan’, the narrator occupies different ages as the novel progresses, giving different ages groups their own opportunity to plug in. And the notion that they equalled stasis while we represented change, that went on to become a very counter-culture concept. The Jefferson Airplane song ’Crown Of Creation’ (1968) wasn’t just inspired by the book, most of its lyrics were barely modified quotes from it. To them it meant generation-war militancy. While its argument may boil down to a credo coined by Frank Zappa: “Without deviation from the norm, progress is not possible.”

But other readings were available. Philip Womack, writing in the Guardian, said:

“I first read ‘The Chrysalids’ when I was 12, an age when any child is beginning to wonder about where he or she fits into the world…. Wyndham's evocation of David's ability… left me reeling with envy and desire; I remember sitting in the library, ‘sending out’ thoughts in the hope that someone, somewhere might catch them.”

The novel’s predicated on breaking away from your elders and their narrow world. David’s parents are the wicked step-parents of fairy tales, in every way apart from them literally being step-parents. They beat him if he’s bad, and lecture him not to be bad if he’s not currently being bad. In general, bar one kindly Uncle, the adult characters only exist insofar as they intrude on the young’s lives, a sense enhanced by the first-person narrative. Which may well be the way you do view adult authority figures when young.

Plus the Fringes provide an evil Uncle, effectively giving us two versions of ‘bad Dad’. They make up the types of Abraham and Cronos, the authoritarian unyielding rule-giver and the malevolent monster who’d destroy his son to steal his girlfriend from him. At twelve we might be more wary of Abraham, feeling these confines are strictures are there to mould us into his own image, prevent us growing into our own person. And notably it’s the older David who encounters the evil Uncle.

Further, when young we often do lead a double life which in a way makes us two selves, acting differently at home with our parents to out with our peers. And it can be easy to imagine one is your true unsullied self, the other an act.

So life in Labrador is in upshot presented as entirely and explicitly negative, a place to flee:

“We had a gift, a sense which should have been a blessing but which was little more than a curse. The stupidest norm was happier; he could feel that he belonged. We did not, and because we did not we had no positive - we were condemned to negatives, to not revealing ourselves, to not speaking when we would, to not using what we know, to not being found out - to a life of perpetual deception, concealment and lying. The prospect of continued negativeness stretching out ahead.”

The early section of the novel read like a ticking clock, a countdown to when they’ll need to go on the run. Whereupon they have to stay ahead of pursuers while awaiting the arrival of Sealand, a telepathic community they’ve managed to make contact with. So Sealand give regular status updates on their rescue, a cross between the Seventh Cavalry and Deliveroo. And in these communications it’s specified how superior Sealand feel to mere norms.

When they do show up, inevitably for the finale, it’s effectively in the form of a UFO. Which again seems uncannily prescient of imagery running through hippie culture, the “silver spaceships” of Neil Young’s ’After The Gold Rush’, the tall Venusians of David Bowie’s ’Memory of a Free Festival’ or (them again) Jefferson Airplane’s ’Have You Seen the Saucers?’ (all 1970).

Their weapon to subdue the norms is a petrifying web, surely a metaphor for the rigidities of their stifling culture. Which might at first appear a mere incapacitant, the humane method of a superior culture. The equivalent of the Tomorrow People’s stun guns, weapons without violence. But this seems done just to later inform us its effects are fatal.

The final chapter’s then given over to the Sealand woman justifying this, in a not dissimilar way to Dr. Vorless calling time on morality in ’Triffids’. Her argument seems to boil down to “it’s okay to kill a thing already dying”. In one of the passages quoted by Jefferson Airplane, she says: “in loyalty to their kind they cannot tolerate our rise; in loyalty to our kind, we cannot tolerate their obstruction.” The seemingly tangential ‘fighting cocks’ cover, not a thing which appears in the book, is presumably designed to represent this. And notably, the one good Norm - kindly Uncle Axel, who would make a more inconvenient corpse, disappears from the narrative before his point.

And, as we may be used to by now, this homo superior business is justified by reference to teleological evolution:

“Did you ever hear of the great lizards? When the time came for them to be superseded they had to pass away.”

The argument is not “there was conflict, the situation became them or us”. The argument is, and quite specifically, “this evolutionary path ain’t big enough for the both of us.” Which, frankly, seems less evolution than eugenics. For one thing, the dinosaurs most likely died as a result of a cosmic accident rather than some grand plan, and besides some reptiles - including fairly big ones - survived to this day. Life on Earth is made of a combination of ancient and more recent species, like you’d expect. For deviation from the norm does not in fact necessitate killing the norm. But the unspoken element of her argument is “we get to say what is dying.”

Which is not something unusual with the Pariah Elites trope. As we saw, in Sturgeon’s ‘More Than Human’, a human character who serves a similarly thwarting plot function is casually killed just to sweep her off-stage. But here the dead don’t even get counted. It’s not the most fannish but the most mainstream instance of this trope which is the most indifferent to loss of life, as soon as it can be labelled ‘norm’ or ’old’.

This sense of generational conflict as something perpetual and innate in human society, it’s very reminiscent of the Futurist manifesto. The Sealand woman’s explanation that one day they too will be replaced finds it’s fore-echo in 1909:

“When we are forty let younger and stronger men than we throw us in the waste paper basket like useless manuscripts..! They will crowd around us, panting with anguish and disappointment, and… will hurl themselves forward to kill us. ...And strong healthy Injustice will shine radiantly from their eyes. For art can only be violence, cruelty, injustice.”

And like the Futurist manifesto you can’t deny the heady excitement of the appeal. While being at the same time aware that this is Social Darwinism speaking.

This was the bullet ’The Tomorrow People’ had wished away through a conspicuous display of performative niceness. ("We're superior, we just don't like to say so.") ’The Chrysalids’ takes it head-on, effectively painting a target on its own chest. And it doesn’t help in the slightest. We just move straight on, as if it hadn't happened, to get to the happy ending.

The very concept of ‘thinking-together’, which binds the book, bakes this in. We can communicate at a higher level, go on to create a better form of living. But not with you. It seems likely that one of the main reasons to give this book its foreign setting was to avoid showing the menfolk of a quaint English village getting it in the neck. The counter-culture notion that we can frolic off into a perfect future, just as soon as we’ve bumped off those troublesome squares, that was already there in 1955.