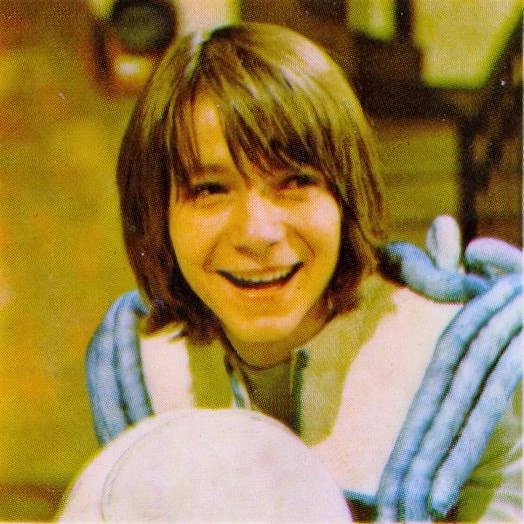

In one fell swoop, ’The Tomorrow People’ effectively named the generation-gap-as-evolution trope, and separated it from the superhero genre. It may be tricky to compare something so Seventies with something equally Sixties. Off duty, the classic X-Men hung around coffee bars where bearded beatnik poets intoned nonsense over bongo drums. While the Tomorrow People sport bouffant hair over wider-than-wide collars or white jumpsuits. So what appear as differences in kind may be merely variations of era. The Tomorrow People are, for example, a pointedly more diverse bunch. But this was also true of the new x-Men, who began in 1975.

Did one influence the other? The X-Men didn’t appear in British Marvel until ’Mighty World of Marvel 49’ (cover date 6/9/73), while ’The Tomorrow People’s’ TV debut was that April. (From when it ran until 1979.) However they had intermittently appeared in Odhams titles in the Sixties and the original American comics were (somewhat haphazardly) distributed over here. So it’s a possibility.

And the underlying concept’s essentially the same - take the concepts ‘mutation’, ’evolution’, ‘generation gap’, ‘brainiac elite’ and blend. Both feature extra-evolved teens, one based in a private school, the other an underground ‘Lab’. Patrician team leader John is essentially Cyclops, and computer Tim a blend of Professor X and Cerebro. (And like Cyclops John was to prove the only continuing character.)

Except I don’t believe there was. If the differences aren’t wide they’re deep, going down to the very heart of the thing. These were undoubtedly different riffs from the same source, arising independently. The more common tale, that they arose from a conversation between Roger Price and David Bowie, seems more on the money.

Let’s focus on a trivial-sounding detail. While the X-Men’s powers are unique to each character, the Tomorrow People share what they refer to as as the three T’s - telepathy, telekinesis and teleportation. (Plus, judging by the first episode, the ability to triangulate from two points.) When a new recruit ‘breaks out’ into their powers, the others are aware what they’re going through as they’ve gone through it themselves, and can offer expert guidance.

And of those T’s, telepathy furthers this feeling of group identity. (The X-Men could communicate mentally with Prof X, but not directly with one another.) The audience appeal of “mind talk” would have been magnified in an era before mobile phones and hand-held devices, when house phones were closely monitored by parents. We’re told “the Tomorrow People are never alone”, and shown one of the group waking and immediately reaching out for telepathic contact with the others.

All the X-Men’s powers were physical, hardly surprisingly as they were devised as super-powers under another name. Even Marvel Girl’s telekinesis is essentially a way of hitting people from a distance. Powers which only Cyclops has problems controlling needing to keep his eyes forever leashed behind his visor or civvy sunglasses, causing no small amount of fretful thought balloons. And this is presented as something of a character quirk, making him unlike the others. (Though it arguably has a greater significance due to him being the Team Leader.)

Whereas the Tomorrow People have a kind of soft power, not concerned with physical strength. To the nerd mind, super-strength is transforming, whether induced by gamma rays, magic words or Charles Atlas booklets. While mind powers give you more of what you already have, or at least what you see yourself as having. Overall, the sell is different. The X-Men more lean into “you get to become yourself”, the TPs into “you get to join the gang”.

But this also means, by genre standards, they have “girl’s powers”. (Though they’re as similar to Professor X as Marvel Girl.) Which isn’t really shied away from. Unlike comics, the screen has no wiggly motion lines. So an established device to portray telekinesis is the firmly upraised hand, like it’s a kind of remote touching. Which isn’t used here. Instead, you just concentrate.

And once you take the super-strength away, the trope starts to overlap with Victorian spiritualism. The Victorians imagined such abilities (‘powers’ seems the wrong word) lent themselves to women and children, who they saw as removed from the material world of men. (When men had them, they were usually marked out as physically frail in some way.) Abilities which were more to do with mediumistically channelling of messages from beyond, with receiving rather than acting.

Yet with the Tomorrow People all so young, and with no direct connection being made between ‘breaking out’ and sexuality, with that pure-white aesthetic, the puberty analogy seems at best latent. So the overlap remains. A magnified psychic link is portrayed via hands laid seance-like upon a glowing table.

The Tomorrow People concept was predicated not just on the concept of linear progress but a kind of teleological utopianism - eventually all humans would develop these latent powers. As that also involved losing the 'primitive' ability to kill (described as “the prime barrier”, rationalised as Nature putting a limit on their powers), global peace thereby awaited us. When first describing them, Carol uses the metaphor of the mind as an unclasping fist, which gets incorporated into the credit sequence. In the same year Britain joined the EU (then the EEC), this evolution will allow Earth to join the Galactic Federation.

So, without the bad mutants… without even the prospect of bad mutants, the one thing which prevents these homo superior abusing their powers is their innate niceness. And with the prime barrier that’s not just assumed, it’s made diegetic, hard-wired in. Asked “You see yourselves as Homo Superior then?” John replies genially, “Well, I don't know about superior, but we are undoubtedly the next stage of human evolution.”

Furthermore, the subsuming of Professor X into Cerebro changes the dynamic. Tim can advise, help out and usefully read out plot points. But they’re not in a school with its inevitable adult authority figure, they have a Lab which is really a futuristic den. Tim conjures up food for them, serving whatever they want. It’s the trope of free range children, not just a nerd gang to join but the adult world held at bay.

And perhaps inevitably, alongside that comes a still greater middle class perspective than the X-Men. (Which, let’s not forget, was set in a private school.) When Stephen’s kidnapped we’re told it cannot be for ransom because his parents aren’t well off, absurdly after we’ve seen their rather plush home. (But then in Britain going on about not being well off is virtually a middle class tell.)

The built-in exception to the rule is Kenny, who seems to have wandered in from ’Grange Hill’. Not just the only black one, he’s presented as more streetwise - seen on first appearance being cheeky to a policeman. We see both his and John’s bedrooms in the same episode, John with astronauts adorning his wall and Kenny footballers. Except… oh my God, they sidelined Kenny. This was mostly to do with the poor performance of the young actor, but still doesn’t help much.

’Tomorrow People’ was broadcast on ITV, Britain’s commercial channel, which at the time many middle class households still stuffily refused to watch. But it was one of ITVs more BBC-ish shows, effectively ’Blue Peter’ with telepathy instead of badges. John could have been a presenter, jaunting from one part of the studio to the next. He just needed a dog. It offered the uncanny on a weekly basis, only to serve up the cosy. (Sample Line: “Some sort of order had to be enforced.”)

You could, however, overstate the differences. There’s a parity of powers among the X-Men, in a way there wasn’t with other super-teams. (From the off, the Avengers featured both the mighty Thor and the winsome Wasp.) And there’s an emphasis on them fighting together, as a team, rather than just alongside one another. As demonstrated in… you guessed it, their first issue when they fight Magneto.

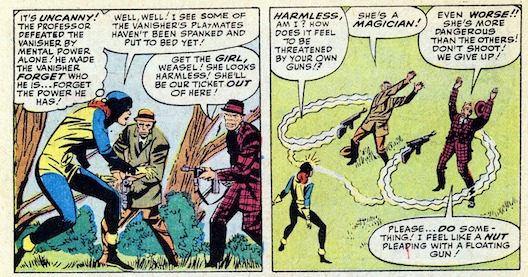

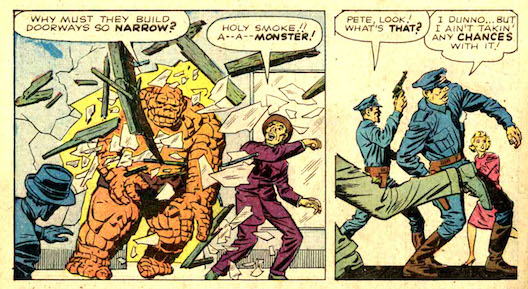

Plus, even if she’s relegated to the back of the first issue cover, Marvel Girl was set up as one of the stronger female characters of the era. The boys’ school reaction to her (essentially “yikes a gal” ) is best consigned to the past, particularly when their spying on her is played for laughs. Yet she’s presented both as powerful and as composed by nature, insisting “I’m not exactly helpless, as you can see.” (Or see the sequence below.) And the Marvel universe often took powers as manifestations of personality. (And she raised the bar. In ’Fantastic Four' 22, Jan ’64, the Invisible Girl’s powers were beefed up essentially by copying Jean’s, just with “psychic” relabelled as “invisible”.)

So, despite their major differences, both series leant heavily into psi powers. And indeed this was part of a general growing interest in such phenomenon through much of the Sixties and Seventies. Both hint heavily these come about through modernity itself. As mentioned last time, ’X-Men’ gestures at atomic radiation. Whereas the opening sequence of ’Tomorrow People’ shows Stephen ‘breaking out’ into his powers via almost breaking down, beset by a cacophony of thought voices in busy central London.

Ostensibly they just trigger, rather than cause, his change. But you can’t imagine the same event in reaction to a Seventeenth century hamlet. There’s the subliminal association of all those voices with mass media broadcasts, reminiscent of the line in the Hawkwind song ’Psi Powers’: “It’s like a radio you can’t switch off.” And the celebrated title sequence, a series of objects flying out at the viewer, could be said to represent the hurtling pace of modernity.

The trope’s often explained by referring to a equally growing interest in anti-materialist New Age claptrap about the Age of Aquarius. And in the first TP story their antagonist Jedikiah poses as a New Age guru. This was a time when the the pseudo-science of parapsychology was taken surprisingly seriously. The interest wasn’t just confined to popular culture but extended to official research. Even the CIA were getting in on it! ’Tomorrow People’, for its part, boasted in its credits of a scientific advisor!

But these all seem not causes but mutually occurring symptoms, coalescing around something else. Unlike the New Agers, we need to find something more material…

The first microchip was made in ’59, though as ever it took a few years to establish its existence. Which signified a wider change, where buttons to press slowly replaced levers to pull. It’s one of the classic transformative devices to be almost entirely unanticipated by the prophecies of science fiction, which carried on blithely believing better always meant bigger.

But once that rule was broken technologically, a ripple effect reached the human. Perhaps future generations might not need biceps to shift the couch or vocal cords to call across rooms, maybe they’d be able to do all it just by thinking hard. It worked in the same way that x-ray and radio technology had in their day stimulated an interest in mediums, by popular association. And it created an era where mind seemed to trump matter.

Conceivably this also lead to the trope of the computer as character. It’s hard to precisely pin this one down as it overlaps so much with the talking computer, which just receives and confirms orders out loud. But Zen in ’Blake’s Seven’ (1978/81) was even made one of the titular band. And the “biological computer” Tim, still more than Zen, is very much a character, one of the gang.

But how, I hear you ask, do these two scenarios play out in terms of stories? Tell you what, let’s look at that next time…