Showing posts with label Comics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Comics. Show all posts

Thursday, 30 June 2022

'FANSCENE' TIMES TWO!

News for comic fans! Not one but two new issues of ‘Fanscene’ have just dropped! And they contain not one but two pieces by me! Respectively ‘Cometh The Hour, Cometh The Zine’, about the Eighties incarnation of the comics zine ‘FA’. (A biiiiig influence on my thinking about comics, back in the day.)

Plus ‘We Come To Bury High Culture, Not To Praise It’, recollections of the small press comics scene of the Nineties and Noughties. Not to mention a whole bunch of other, and no doubt better, stuff, courtesy the tireless efforts of compiler David Hathaway-Price.

In these cash-strapped times, PDF versions are free to download, via this link. These are likely to be the last issues, and I myself am semi-retired from comics. In fact I’ve even forgotten how to spell ‘sequential’.

Saturday, 5 March 2022

THE X-MEN VS. THE TOMORROW PEOPLE, ROUND TWO

(This third helping of Mutants Are Our Future compares the story scenarios of the original Marvel comic strip ‘The X-Men’ with the British kids’ TV show ‘The Tomorrow People’. Previous part here.)

The classic Lee/Kirby era of ’The X-Men’ (effectively the first nineteen issues) essentially features two types of story, themselves determined by two types of antagonist. Handily, they arrive consecutively. Following Magneto’s appearance in the first issue, bad mutants become the good mutants’ default foe. While Marvel usually rotated their rogue’s gallery, the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants (Magneto, plus his henchmen) came back in issues 4, 5, 6 and 7, and were already being called ‘The Evil You-Know-Who’ on the cover of 6.

Adjacent panels often juxtapose the fair-play teamwork of the X-Men against the fractious world of the Brotherhood. Who represent about every way to fail to form a brotherhood; the imperiously commanding Magneto, the obsequious Toad (whose excessive fawning even gets on his master’s nerves), the scheming underling Mastermind, and Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch, trapped by their misapplied sense of duty to Magneto.

Then, as if suddenly noticing how reliant on the Brotherhood they’d become, Lee and Kirby put them out of harm’s way by splitting them up in three different directions. And segue straight into the first Sentinels story. This is clearly intended as something of an epic. It’s not just the first three-part run, even the next issue is largely devoted to the battle’s aftermath.

The Sentinels, as we all know by now, were designed precisely to eliminate the mutant “threat”. Public fear and distrust of the super-powered had long been a distinct feature of Marvel, distinguishing it from DC. Now it comes into its own.

Except here it’s specified precisely as public distrust. Crowds in the street are likely to degenerate into anti-mutie lynch mobs at any sign of unorthodox behaviour. This includes cops, but government and military... they clearly know better. In issue 10 Professor X says casually “Washington has already contacted me” about the latest drama. So the constituency of their designer Trask isn’t ranting Republicans but the salacious popular press. He even launches the Sentinels on live TV.

As robots tend to, the Sentinels then rebel. But this is because they decide the best way to carry out their orders, to protect humanity, is to subjugate them. The story them becomes a parable about the rise of, but also the inherent deficiencies with, machines. They’re often depicted neatly lined up, like beans on a shelf, while their plot is essentially to make more of themselves. But they’re also shown lacking the basics of gumption and initiative.

‘Mutant’ would seem a very science fiction word. But there’s only one alien in the whole Lee/Kirby run, the Stranger, who appears in ’The Triumph of Magneto’ (11). Both sides assume him to be a mutant and so set about trying to win him over to their camp. Only to discover he’s not just literally but conceptually alien, outside their common frame of references. (“Have I not said I am… a stranger?” he asks, channelling Leonard Cohen.) His only interest is in collecting specimens of mutation for study. He picks Magneto, for plot convenient reasons.

Whereas, as we’ve seen the Tomorrow People comes with a plot contrivance where the whole concept of bad Tomorrow People, in brotherhoods or otherwise, is blocked off. Instead, with their first story ’The Slaves of Jedikiah’ (1973) their antagonists are established as aliens.

While Magneto tries to misuse the power of the mutants he manages to pick for his side, Jedikiah tries to limit his, with the recurrent one-eyed motif, with constraining anti-telepathic headbands and the like. There’s a moment where Stephen, rather half-heartedly, Refuses The Call and sulkily claims he’s not a real Tomorrow Person after all. But the premise is auto-inoculated against him voluntarily taking Jedikiah’s side.

Jedikiah turns out to be the henchman of a bigger baddie called (confusing our comparison) the Cyclops. Except, in the very last episode he suddenly switches to sympathetic. As it turns out, his spaceship was broken and he really just needed the psychic equivalent of a push to get him home again. This becomes something of a show staple - not resolving conflicts so much as wishing them away, making it never-was. And one way to manage this is to decide at the last minute the bad guy was just misunderstood. The Prime Barrier perhaps necessitates this. They can’t fight a deciding battle because they don’t fight, so everything has to just turn out to be okay.

There’s some suggestion the Cyclops was simply scared of us (“your planet has an evil reputation throughout the galaxy… you are always at war”), which might be more convincing if he hadn’t recruited human henchmen. In a vain bid to keep the story propulsive, the antagonism abruptly switches to Jedikiah, who in short order is revealed as a robot, goes mad and starts rampaging round Cyclops’ spaceship. (Some robots revolt. Others go mad. Them’s the breaks.)

As we saw another time, the monsters in ’Dr. Who’ tend to be human foibles, which are magnified, externalised and then stuffed in a rubber suit. The penchant of ’Tomorrow People’ is for more generalised social ills which turn out to be the fault of menacing aliens; gang warfare (‘The Blue and the Green’), the fashionability of fascism (‘Hitler’s Last Secret’) and so on. Except, as we’ve seen, they’re not really the aliens’ fault either. They shilly-shally between manipulative monsters and the equivalent of the Stranger.

Human hostility is established. Well, mentioned. Told the TPs can’t make war, Stephen asks the not-unreasonable question “what if someone makes war on us?” While the Cyclops warns them: “Arm yourself against your own species. They will kill you if they find you out.” But unlike the X-Men, unlike every Marvel hero ever, this secrecy doesn’t apply to their own parents. It’s taken for granted Stephen’s must be told.

Human mistrust only really appears with the biker gang who aid Jedikiah. Except ‘aid’ is a loose term, and he’s forever telling the serial bunglers “no more incompetence will be tolerated.” Which makes you wonder why he thought he needed them in the first place.

Their outlaw attire suggests that rather than adult authority figures they’re ‘bad kids’, the delinquent hooligans who plagued Seventies popular culture. They even have laddish nicknames, Ginge and Lefty. Which leads to an emphasis on brains triumphing over brawn, as if they’ve been set up to fail. There’s a scene where the TPs repeatedly jaunt out of their charging way, leaving them to fall in lakes and other hilarious consequences, which recalls the ghost cat taunting the live dog in the Hanna-Barbera cartoon ’The Funky Phantom’.

We’re told rather late on that they were recruited ideologically, told “you lot were just a bunch of freaks”. But this shows up out of nowhere, and is used as a convenience for them to swap sides, following the show’s No True Villains rule. Like school bullies, they’re tauntingly confrontational on the outside but really need the nerd kids’ help. From that point on they reappear as the pacifists’ handy contracted-out muscle, a little like the Ian role in ’Doctor Who’.

’Secret Weapon' (1975) is the nearest to a Sentinels-like story. Opening the third season it again introduces a new Tomorrow Person who’s conveniently ‘breaking out’, Tyso. Who’s wanted by a secret Government department, to make him the secret weapon of the title. The distinction between him and them is established with a first shot, a toff car appearing on the road behind other gypsy kids as they play. And of course experiments on gypsies recall Nazi horrors.

The story’s tension lies between Professor Cawston and Colonel Masters, scientific curiosity against military instrumentalisation. One is handily colour-coded black and the other beige, against the Tomorrow People’s perpetual white. And like Jedikiah though he seeks to harness their powers, Masters spends virtually the whole time dampening them, giving Guards “dope guns”, placing Tyso and Stephen in comas.

In this way it’s almost the inverse of the Sentinels, the military being informed becoming the very problem. “Can you imagine living your whole life in a tribe of monkeys?” Cawston asks Masters. “With your very survival depending upon their not finding out you’re a human being, a superior creature?” But Masters’ reaction to their powers is not so much fearful as avaricious.

Writer and series creator Roger Price was in many ways an old Sixties radical, and the story resounds with anti-establishment and internationalist pacifism. Though he’s careful enough to portray Masters as sincere in his beliefs, however ruthless, allowing him counters in a stand-off argument with Elizabeth. (When he asks what would happen if such powers were to develop in Russia or China she replies there’d simply be more Tomorrow People like us, perhaps the series’ ethos encapsulated.)

But then the finale is a let-down even by the standards of the show, whether measured dramatically or politically. They essentially defeat military intelligence by going to its manager, leading to the so-bad-its-great line “what’s the Prime Minister doing here?” To get to the PM, they need to jauntingly kidnap him, which luckily he is rather sanguine about. See, kids? The system works.

Worse still, Chris, not a Tomorrow Person, can be presented as less enlightened, a slightly less street-level Ginge and Lefty. He’s essentially the hot-headed agitational radical, the peace hawk, against John’s sober-minded faith in reason. He’s even willing to threaten the old boy with a “Martian ray gun”, only for John to give the game away. Yet it’s him who cooks up this half-baked plan in the first place!

And the two most interesting features of the story, that the Tomorrow People initially underestimate Masters’ threat, and that his assistant is herself a telepath, are essentially orphaned by this rubbish resolution. Her powers seem lesser than the TPs, and are limited to telepathy, but still seem to grant her greater empathy than Masters. This is eventually explained as her being a kind of forerunner, who failed to fully break out.

And while Tyso may seem another point won for diversity casting, his actual role in the story is so slight he’s effectively a boy damsel in distress. He really does spend most of his time asleep, so much that he nearly gets forgotten at the end. And his Romany family are portrayed absurdly, his father even willing to sell him to Masters! The message would seem to be that we are such generous and tolerant folk, we even apply it to these backward Gyppo types.

Which shouldn’t surprise us. Frequently referred to as a critique of racism, this trope’s perhaps worse than useless for that. It exists to flatter its audience, convincing them it works as some sort of anti-racist credential, like those diversity training certificates workplaces give you. The truth is, people follow this stuff because they like to see some bigged up version of themselves, particularly with bigged up brains and hearts.

Being part of a band of elite pariahs, the tension over this trope is how much it can be a fantasy and how much a phobia. Witch-like powers come with witch hunts, after all. (As future instalments in this series will show, a feature of this trope is the way it weaves between kids’ TV shows and outright horror films.) This can be used creatively, making the dish into a sweet and sour.

’X-Men’ got this at some level, ’Tomorrow People’ less so. True, it suffered from cheap budgets even if compared to the often-mocked ’Doctor Who’, and from often-excruciating child acting. But chiefly it feels auto-inoculated against everything which might make its own scenario involving. Its utopianism may seem distant from us now, so it’s tempting to frame the problem as to do with eras. But it was dramatic too, forever presenting us with an enticing situation of conflict then whisking that conflict away. It took a great premise and fumbled it with wooly well-meaningness.

The classic Lee/Kirby era of ’The X-Men’ (effectively the first nineteen issues) essentially features two types of story, themselves determined by two types of antagonist. Handily, they arrive consecutively. Following Magneto’s appearance in the first issue, bad mutants become the good mutants’ default foe. While Marvel usually rotated their rogue’s gallery, the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants (Magneto, plus his henchmen) came back in issues 4, 5, 6 and 7, and were already being called ‘The Evil You-Know-Who’ on the cover of 6.

Adjacent panels often juxtapose the fair-play teamwork of the X-Men against the fractious world of the Brotherhood. Who represent about every way to fail to form a brotherhood; the imperiously commanding Magneto, the obsequious Toad (whose excessive fawning even gets on his master’s nerves), the scheming underling Mastermind, and Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch, trapped by their misapplied sense of duty to Magneto.

Then, as if suddenly noticing how reliant on the Brotherhood they’d become, Lee and Kirby put them out of harm’s way by splitting them up in three different directions. And segue straight into the first Sentinels story. This is clearly intended as something of an epic. It’s not just the first three-part run, even the next issue is largely devoted to the battle’s aftermath.

The Sentinels, as we all know by now, were designed precisely to eliminate the mutant “threat”. Public fear and distrust of the super-powered had long been a distinct feature of Marvel, distinguishing it from DC. Now it comes into its own.

Except here it’s specified precisely as public distrust. Crowds in the street are likely to degenerate into anti-mutie lynch mobs at any sign of unorthodox behaviour. This includes cops, but government and military... they clearly know better. In issue 10 Professor X says casually “Washington has already contacted me” about the latest drama. So the constituency of their designer Trask isn’t ranting Republicans but the salacious popular press. He even launches the Sentinels on live TV.

As robots tend to, the Sentinels then rebel. But this is because they decide the best way to carry out their orders, to protect humanity, is to subjugate them. The story them becomes a parable about the rise of, but also the inherent deficiencies with, machines. They’re often depicted neatly lined up, like beans on a shelf, while their plot is essentially to make more of themselves. But they’re also shown lacking the basics of gumption and initiative.

‘Mutant’ would seem a very science fiction word. But there’s only one alien in the whole Lee/Kirby run, the Stranger, who appears in ’The Triumph of Magneto’ (11). Both sides assume him to be a mutant and so set about trying to win him over to their camp. Only to discover he’s not just literally but conceptually alien, outside their common frame of references. (“Have I not said I am… a stranger?” he asks, channelling Leonard Cohen.) His only interest is in collecting specimens of mutation for study. He picks Magneto, for plot convenient reasons.

Whereas, as we’ve seen the Tomorrow People comes with a plot contrivance where the whole concept of bad Tomorrow People, in brotherhoods or otherwise, is blocked off. Instead, with their first story ’The Slaves of Jedikiah’ (1973) their antagonists are established as aliens.

While Magneto tries to misuse the power of the mutants he manages to pick for his side, Jedikiah tries to limit his, with the recurrent one-eyed motif, with constraining anti-telepathic headbands and the like. There’s a moment where Stephen, rather half-heartedly, Refuses The Call and sulkily claims he’s not a real Tomorrow Person after all. But the premise is auto-inoculated against him voluntarily taking Jedikiah’s side.

Jedikiah turns out to be the henchman of a bigger baddie called (confusing our comparison) the Cyclops. Except, in the very last episode he suddenly switches to sympathetic. As it turns out, his spaceship was broken and he really just needed the psychic equivalent of a push to get him home again. This becomes something of a show staple - not resolving conflicts so much as wishing them away, making it never-was. And one way to manage this is to decide at the last minute the bad guy was just misunderstood. The Prime Barrier perhaps necessitates this. They can’t fight a deciding battle because they don’t fight, so everything has to just turn out to be okay.

There’s some suggestion the Cyclops was simply scared of us (“your planet has an evil reputation throughout the galaxy… you are always at war”), which might be more convincing if he hadn’t recruited human henchmen. In a vain bid to keep the story propulsive, the antagonism abruptly switches to Jedikiah, who in short order is revealed as a robot, goes mad and starts rampaging round Cyclops’ spaceship. (Some robots revolt. Others go mad. Them’s the breaks.)

As we saw another time, the monsters in ’Dr. Who’ tend to be human foibles, which are magnified, externalised and then stuffed in a rubber suit. The penchant of ’Tomorrow People’ is for more generalised social ills which turn out to be the fault of menacing aliens; gang warfare (‘The Blue and the Green’), the fashionability of fascism (‘Hitler’s Last Secret’) and so on. Except, as we’ve seen, they’re not really the aliens’ fault either. They shilly-shally between manipulative monsters and the equivalent of the Stranger.

Human hostility is established. Well, mentioned. Told the TPs can’t make war, Stephen asks the not-unreasonable question “what if someone makes war on us?” While the Cyclops warns them: “Arm yourself against your own species. They will kill you if they find you out.” But unlike the X-Men, unlike every Marvel hero ever, this secrecy doesn’t apply to their own parents. It’s taken for granted Stephen’s must be told.

Human mistrust only really appears with the biker gang who aid Jedikiah. Except ‘aid’ is a loose term, and he’s forever telling the serial bunglers “no more incompetence will be tolerated.” Which makes you wonder why he thought he needed them in the first place.

Their outlaw attire suggests that rather than adult authority figures they’re ‘bad kids’, the delinquent hooligans who plagued Seventies popular culture. They even have laddish nicknames, Ginge and Lefty. Which leads to an emphasis on brains triumphing over brawn, as if they’ve been set up to fail. There’s a scene where the TPs repeatedly jaunt out of their charging way, leaving them to fall in lakes and other hilarious consequences, which recalls the ghost cat taunting the live dog in the Hanna-Barbera cartoon ’The Funky Phantom’.

We’re told rather late on that they were recruited ideologically, told “you lot were just a bunch of freaks”. But this shows up out of nowhere, and is used as a convenience for them to swap sides, following the show’s No True Villains rule. Like school bullies, they’re tauntingly confrontational on the outside but really need the nerd kids’ help. From that point on they reappear as the pacifists’ handy contracted-out muscle, a little like the Ian role in ’Doctor Who’.

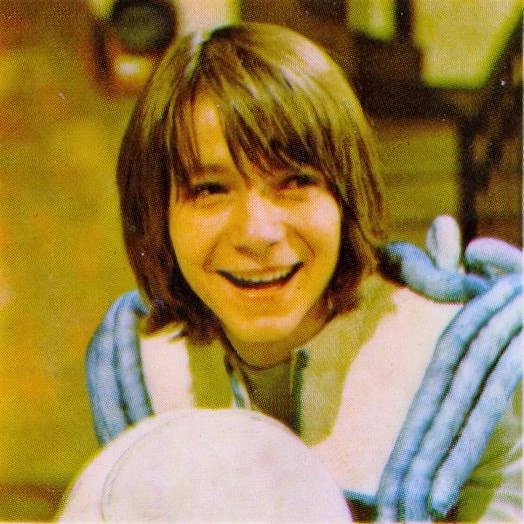

’Secret Weapon' (1975) is the nearest to a Sentinels-like story. Opening the third season it again introduces a new Tomorrow Person who’s conveniently ‘breaking out’, Tyso. Who’s wanted by a secret Government department, to make him the secret weapon of the title. The distinction between him and them is established with a first shot, a toff car appearing on the road behind other gypsy kids as they play. And of course experiments on gypsies recall Nazi horrors.

The story’s tension lies between Professor Cawston and Colonel Masters, scientific curiosity against military instrumentalisation. One is handily colour-coded black and the other beige, against the Tomorrow People’s perpetual white. And like Jedikiah though he seeks to harness their powers, Masters spends virtually the whole time dampening them, giving Guards “dope guns”, placing Tyso and Stephen in comas.

In this way it’s almost the inverse of the Sentinels, the military being informed becoming the very problem. “Can you imagine living your whole life in a tribe of monkeys?” Cawston asks Masters. “With your very survival depending upon their not finding out you’re a human being, a superior creature?” But Masters’ reaction to their powers is not so much fearful as avaricious.

Writer and series creator Roger Price was in many ways an old Sixties radical, and the story resounds with anti-establishment and internationalist pacifism. Though he’s careful enough to portray Masters as sincere in his beliefs, however ruthless, allowing him counters in a stand-off argument with Elizabeth. (When he asks what would happen if such powers were to develop in Russia or China she replies there’d simply be more Tomorrow People like us, perhaps the series’ ethos encapsulated.)

But then the finale is a let-down even by the standards of the show, whether measured dramatically or politically. They essentially defeat military intelligence by going to its manager, leading to the so-bad-its-great line “what’s the Prime Minister doing here?” To get to the PM, they need to jauntingly kidnap him, which luckily he is rather sanguine about. See, kids? The system works.

Worse still, Chris, not a Tomorrow Person, can be presented as less enlightened, a slightly less street-level Ginge and Lefty. He’s essentially the hot-headed agitational radical, the peace hawk, against John’s sober-minded faith in reason. He’s even willing to threaten the old boy with a “Martian ray gun”, only for John to give the game away. Yet it’s him who cooks up this half-baked plan in the first place!

And the two most interesting features of the story, that the Tomorrow People initially underestimate Masters’ threat, and that his assistant is herself a telepath, are essentially orphaned by this rubbish resolution. Her powers seem lesser than the TPs, and are limited to telepathy, but still seem to grant her greater empathy than Masters. This is eventually explained as her being a kind of forerunner, who failed to fully break out.

And while Tyso may seem another point won for diversity casting, his actual role in the story is so slight he’s effectively a boy damsel in distress. He really does spend most of his time asleep, so much that he nearly gets forgotten at the end. And his Romany family are portrayed absurdly, his father even willing to sell him to Masters! The message would seem to be that we are such generous and tolerant folk, we even apply it to these backward Gyppo types.

Which shouldn’t surprise us. Frequently referred to as a critique of racism, this trope’s perhaps worse than useless for that. It exists to flatter its audience, convincing them it works as some sort of anti-racist credential, like those diversity training certificates workplaces give you. The truth is, people follow this stuff because they like to see some bigged up version of themselves, particularly with bigged up brains and hearts.

Being part of a band of elite pariahs, the tension over this trope is how much it can be a fantasy and how much a phobia. Witch-like powers come with witch hunts, after all. (As future instalments in this series will show, a feature of this trope is the way it weaves between kids’ TV shows and outright horror films.) This can be used creatively, making the dish into a sweet and sour.

’X-Men’ got this at some level, ’Tomorrow People’ less so. True, it suffered from cheap budgets even if compared to the often-mocked ’Doctor Who’, and from often-excruciating child acting. But chiefly it feels auto-inoculated against everything which might make its own scenario involving. Its utopianism may seem distant from us now, so it’s tempting to frame the problem as to do with eras. But it was dramatic too, forever presenting us with an enticing situation of conflict then whisking that conflict away. It took a great premise and fumbled it with wooly well-meaningness.

Coming soon! More mutants, more future...

Saturday, 26 February 2022

THE X-MEN VS. THE TOMORROW PEOPLE

(The second instalment in our new series Mutants Are Our Future crashes the classic American comic series against the British TV show to see what sparks. Previous part, on the X-Men versus the Fantastic Four, lies here.)

In one fell swoop, ’The Tomorrow People’ effectively named the generation-gap-as-evolution trope, and separated it from the superhero genre. It may be tricky to compare something so Seventies with something equally Sixties. Off duty, the classic X-Men hung around coffee bars where bearded beatnik poets intoned nonsense over bongo drums. While the Tomorrow People sport bouffant hair over wider-than-wide collars or white jumpsuits. So what appear as differences in kind may be merely variations of era. The Tomorrow People are, for example, a pointedly more diverse bunch. But this was also true of the new x-Men, who began in 1975.

Did one influence the other? The X-Men didn’t appear in British Marvel until ’Mighty World of Marvel 49’ (cover date 6/9/73), while ’The Tomorrow People’s’ TV debut was that April. (From when it ran until 1979.) However they had intermittently appeared in Odhams titles in the Sixties and the original American comics were (somewhat haphazardly) distributed over here. So it’s a possibility.

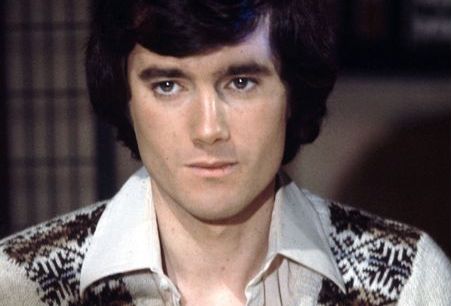

And the underlying concept’s essentially the same - take the concepts ‘mutation’, ’evolution’, ‘generation gap’, ‘brainiac elite’ and blend. Both feature extra-evolved teens, one based in a private school, the other an underground ‘Lab’. Patrician team leader John is essentially Cyclops, and computer Tim a blend of Professor X and Cerebro. (And like Cyclops John was to prove the only continuing character.)

Except I don’t believe there was. If the differences aren’t wide they’re deep, going down to the very heart of the thing. These were undoubtedly different riffs from the same source, arising independently. The more common tale, that they arose from a conversation between Roger Price and David Bowie, seems more on the money.

Let’s focus on a trivial-sounding detail. While the X-Men’s powers are unique to each character, the Tomorrow People share what they refer to as as the three T’s - telepathy, telekinesis and teleportation. (Plus, judging by the first episode, the ability to triangulate from two points.) When a new recruit ‘breaks out’ into their powers, the others are aware what they’re going through as they’ve gone through it themselves, and can offer expert guidance.

And of those T’s, telepathy furthers this feeling of group identity. (The X-Men could communicate mentally with Prof X, but not directly with one another.) The audience appeal of “mind talk” would have been magnified in an era before mobile phones and hand-held devices, when house phones were closely monitored by parents. We’re told “the Tomorrow People are never alone”, and shown one of the group waking and immediately reaching out for telepathic contact with the others.

All the X-Men’s powers were physical, hardly surprisingly as they were devised as super-powers under another name. Even Marvel Girl’s telekinesis is essentially a way of hitting people from a distance. Powers which only Cyclops has problems controlling needing to keep his eyes forever leashed behind his visor or civvy sunglasses, causing no small amount of fretful thought balloons. And this is presented as something of a character quirk, making him unlike the others. (Though it arguably has a greater significance due to him being the Team Leader.)

Whereas the Tomorrow People have a kind of soft power, not concerned with physical strength. To the nerd mind, super-strength is transforming, whether induced by gamma rays, magic words or Charles Atlas booklets. While mind powers give you more of what you already have, or at least what you see yourself as having. Overall, the sell is different. The X-Men more lean into “you get to become yourself”, the TPs into “you get to join the gang”.

But this also means, by genre standards, they have “girl’s powers”. (Though they’re as similar to Professor X as Marvel Girl.) Which isn’t really shied away from. Unlike comics, the screen has no wiggly motion lines. So an established device to portray telekinesis is the firmly upraised hand, like it’s a kind of remote touching. Which isn’t used here. Instead, you just concentrate.

And once you take the super-strength away, the trope starts to overlap with Victorian spiritualism. The Victorians imagined such abilities (‘powers’ seems the wrong word) lent themselves to women and children, who they saw as removed from the material world of men. (When men had them, they were usually marked out as physically frail in some way.) Abilities which were more to do with mediumistically channelling of messages from beyond, with receiving rather than acting.

Yet with the Tomorrow People all so young, and with no direct connection being made between ‘breaking out’ and sexuality, with that pure-white aesthetic, the puberty analogy seems at best latent. So the overlap remains. A magnified psychic link is portrayed via hands laid seance-like upon a glowing table.

The Tomorrow People concept was predicated not just on the concept of linear progress but a kind of teleological utopianism - eventually all humans would develop these latent powers. As that also involved losing the 'primitive' ability to kill (described as “the prime barrier”, rationalised as Nature putting a limit on their powers), global peace thereby awaited us. When first describing them, Carol uses the metaphor of the mind as an unclasping fist, which gets incorporated into the credit sequence. In the same year Britain joined the EU (then the EEC), this evolution will allow Earth to join the Galactic Federation.

So, without the bad mutants… without even the prospect of bad mutants, the one thing which prevents these homo superior abusing their powers is their innate niceness. And with the prime barrier that’s not just assumed, it’s made diegetic, hard-wired in. Asked “You see yourselves as Homo Superior then?” John replies genially, “Well, I don't know about superior, but we are undoubtedly the next stage of human evolution.”

Furthermore, the subsuming of Professor X into Cerebro changes the dynamic. Tim can advise, help out and usefully read out plot points. But they’re not in a school with its inevitable adult authority figure, they have a Lab which is really a futuristic den. Tim conjures up food for them, serving whatever they want. It’s the trope of free range children, not just a nerd gang to join but the adult world held at bay.

And perhaps inevitably, alongside that comes a still greater middle class perspective than the X-Men. (Which, let’s not forget, was set in a private school.) When Stephen’s kidnapped we’re told it cannot be for ransom because his parents aren’t well off, absurdly after we’ve seen their rather plush home. (But then in Britain going on about not being well off is virtually a middle class tell.)

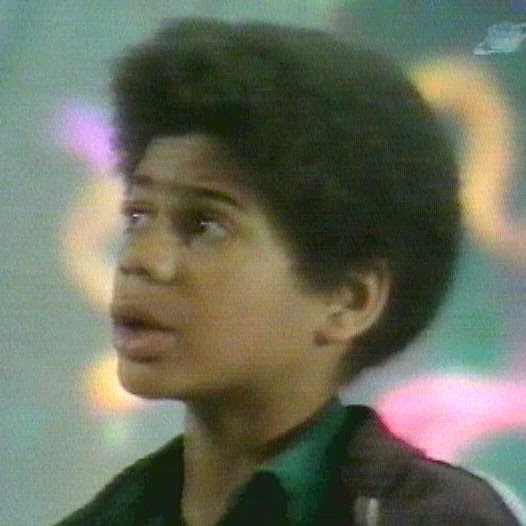

The built-in exception to the rule is Kenny, who seems to have wandered in from ’Grange Hill’. Not just the only black one, he’s presented as more streetwise - seen on first appearance being cheeky to a policeman. We see both his and John’s bedrooms in the same episode, John with astronauts adorning his wall and Kenny footballers. Except… oh my God, they sidelined Kenny. This was mostly to do with the poor performance of the young actor, but still doesn’t help much.

’Tomorrow People’ was broadcast on ITV, Britain’s commercial channel, which at the time many middle class households still stuffily refused to watch. But it was one of ITVs more BBC-ish shows, effectively ’Blue Peter’ with telepathy instead of badges. John could have been a presenter, jaunting from one part of the studio to the next. He just needed a dog. It offered the uncanny on a weekly basis, only to serve up the cosy. (Sample Line: “Some sort of order had to be enforced.”)

You could, however, overstate the differences. There’s a parity of powers among the X-Men, in a way there wasn’t with other super-teams. (From the off, the Avengers featured both the mighty Thor and the winsome Wasp.) And there’s an emphasis on them fighting together, as a team, rather than just alongside one another. As demonstrated in… you guessed it, their first issue when they fight Magneto.

Plus, even if she’s relegated to the back of the first issue cover, Marvel Girl was set up as one of the stronger female characters of the era. The boys’ school reaction to her (essentially “yikes a gal” ) is best consigned to the past, particularly when their spying on her is played for laughs. Yet she’s presented both as powerful and as composed by nature, insisting “I’m not exactly helpless, as you can see.” (Or see the sequence below.) And the Marvel universe often took powers as manifestations of personality. (And she raised the bar. In ’Fantastic Four' 22, Jan ’64, the Invisible Girl’s powers were beefed up essentially by copying Jean’s, just with “psychic” relabelled as “invisible”.)

So, despite their major differences, both series leant heavily into psi powers. And indeed this was part of a general growing interest in such phenomenon through much of the Sixties and Seventies. Both hint heavily these come about through modernity itself. As mentioned last time, ’X-Men’ gestures at atomic radiation. Whereas the opening sequence of ’Tomorrow People’ shows Stephen ‘breaking out’ into his powers via almost breaking down, beset by a cacophony of thought voices in busy central London.

Ostensibly they just trigger, rather than cause, his change. But you can’t imagine the same event in reaction to a Seventeenth century hamlet. There’s the subliminal association of all those voices with mass media broadcasts, reminiscent of the line in the Hawkwind song ’Psi Powers’: “It’s like a radio you can’t switch off.” And the celebrated title sequence, a series of objects flying out at the viewer, could be said to represent the hurtling pace of modernity.

The trope’s often explained by referring to a equally growing interest in anti-materialist New Age claptrap about the Age of Aquarius. And in the first TP story their antagonist Jedikiah poses as a New Age guru. This was a time when the the pseudo-science of parapsychology was taken surprisingly seriously. The interest wasn’t just confined to popular culture but extended to official research. Even the CIA were getting in on it! ’Tomorrow People’, for its part, boasted in its credits of a scientific advisor!

But these all seem not causes but mutually occurring symptoms, coalescing around something else. Unlike the New Agers, we need to find something more material…

The first microchip was made in ’59, though as ever it took a few years to establish its existence. Which signified a wider change, where buttons to press slowly replaced levers to pull. It’s one of the classic transformative devices to be almost entirely unanticipated by the prophecies of science fiction, which carried on blithely believing better always meant bigger.

But once that rule was broken technologically, a ripple effect reached the human. Perhaps future generations might not need biceps to shift the couch or vocal cords to call across rooms, maybe they’d be able to do all it just by thinking hard. It worked in the same way that x-ray and radio technology had in their day stimulated an interest in mediums, by popular association. And it created an era where mind seemed to trump matter.

Conceivably this also lead to the trope of the computer as character. It’s hard to precisely pin this one down as it overlaps so much with the talking computer, which just receives and confirms orders out loud. But Zen in ’Blake’s Seven’ (1978/81) was even made one of the titular band. And the “biological computer” Tim, still more than Zen, is very much a character, one of the gang.

But how, I hear you ask, do these two scenarios play out in terms of stories? Tell you what, let’s look at that next time…

In one fell swoop, ’The Tomorrow People’ effectively named the generation-gap-as-evolution trope, and separated it from the superhero genre. It may be tricky to compare something so Seventies with something equally Sixties. Off duty, the classic X-Men hung around coffee bars where bearded beatnik poets intoned nonsense over bongo drums. While the Tomorrow People sport bouffant hair over wider-than-wide collars or white jumpsuits. So what appear as differences in kind may be merely variations of era. The Tomorrow People are, for example, a pointedly more diverse bunch. But this was also true of the new x-Men, who began in 1975.

Did one influence the other? The X-Men didn’t appear in British Marvel until ’Mighty World of Marvel 49’ (cover date 6/9/73), while ’The Tomorrow People’s’ TV debut was that April. (From when it ran until 1979.) However they had intermittently appeared in Odhams titles in the Sixties and the original American comics were (somewhat haphazardly) distributed over here. So it’s a possibility.

And the underlying concept’s essentially the same - take the concepts ‘mutation’, ’evolution’, ‘generation gap’, ‘brainiac elite’ and blend. Both feature extra-evolved teens, one based in a private school, the other an underground ‘Lab’. Patrician team leader John is essentially Cyclops, and computer Tim a blend of Professor X and Cerebro. (And like Cyclops John was to prove the only continuing character.)

Except I don’t believe there was. If the differences aren’t wide they’re deep, going down to the very heart of the thing. These were undoubtedly different riffs from the same source, arising independently. The more common tale, that they arose from a conversation between Roger Price and David Bowie, seems more on the money.

Let’s focus on a trivial-sounding detail. While the X-Men’s powers are unique to each character, the Tomorrow People share what they refer to as as the three T’s - telepathy, telekinesis and teleportation. (Plus, judging by the first episode, the ability to triangulate from two points.) When a new recruit ‘breaks out’ into their powers, the others are aware what they’re going through as they’ve gone through it themselves, and can offer expert guidance.

And of those T’s, telepathy furthers this feeling of group identity. (The X-Men could communicate mentally with Prof X, but not directly with one another.) The audience appeal of “mind talk” would have been magnified in an era before mobile phones and hand-held devices, when house phones were closely monitored by parents. We’re told “the Tomorrow People are never alone”, and shown one of the group waking and immediately reaching out for telepathic contact with the others.

All the X-Men’s powers were physical, hardly surprisingly as they were devised as super-powers under another name. Even Marvel Girl’s telekinesis is essentially a way of hitting people from a distance. Powers which only Cyclops has problems controlling needing to keep his eyes forever leashed behind his visor or civvy sunglasses, causing no small amount of fretful thought balloons. And this is presented as something of a character quirk, making him unlike the others. (Though it arguably has a greater significance due to him being the Team Leader.)

Whereas the Tomorrow People have a kind of soft power, not concerned with physical strength. To the nerd mind, super-strength is transforming, whether induced by gamma rays, magic words or Charles Atlas booklets. While mind powers give you more of what you already have, or at least what you see yourself as having. Overall, the sell is different. The X-Men more lean into “you get to become yourself”, the TPs into “you get to join the gang”.

But this also means, by genre standards, they have “girl’s powers”. (Though they’re as similar to Professor X as Marvel Girl.) Which isn’t really shied away from. Unlike comics, the screen has no wiggly motion lines. So an established device to portray telekinesis is the firmly upraised hand, like it’s a kind of remote touching. Which isn’t used here. Instead, you just concentrate.

And once you take the super-strength away, the trope starts to overlap with Victorian spiritualism. The Victorians imagined such abilities (‘powers’ seems the wrong word) lent themselves to women and children, who they saw as removed from the material world of men. (When men had them, they were usually marked out as physically frail in some way.) Abilities which were more to do with mediumistically channelling of messages from beyond, with receiving rather than acting.

Yet with the Tomorrow People all so young, and with no direct connection being made between ‘breaking out’ and sexuality, with that pure-white aesthetic, the puberty analogy seems at best latent. So the overlap remains. A magnified psychic link is portrayed via hands laid seance-like upon a glowing table.

The Tomorrow People concept was predicated not just on the concept of linear progress but a kind of teleological utopianism - eventually all humans would develop these latent powers. As that also involved losing the 'primitive' ability to kill (described as “the prime barrier”, rationalised as Nature putting a limit on their powers), global peace thereby awaited us. When first describing them, Carol uses the metaphor of the mind as an unclasping fist, which gets incorporated into the credit sequence. In the same year Britain joined the EU (then the EEC), this evolution will allow Earth to join the Galactic Federation.

So, without the bad mutants… without even the prospect of bad mutants, the one thing which prevents these homo superior abusing their powers is their innate niceness. And with the prime barrier that’s not just assumed, it’s made diegetic, hard-wired in. Asked “You see yourselves as Homo Superior then?” John replies genially, “Well, I don't know about superior, but we are undoubtedly the next stage of human evolution.”

Furthermore, the subsuming of Professor X into Cerebro changes the dynamic. Tim can advise, help out and usefully read out plot points. But they’re not in a school with its inevitable adult authority figure, they have a Lab which is really a futuristic den. Tim conjures up food for them, serving whatever they want. It’s the trope of free range children, not just a nerd gang to join but the adult world held at bay.

And perhaps inevitably, alongside that comes a still greater middle class perspective than the X-Men. (Which, let’s not forget, was set in a private school.) When Stephen’s kidnapped we’re told it cannot be for ransom because his parents aren’t well off, absurdly after we’ve seen their rather plush home. (But then in Britain going on about not being well off is virtually a middle class tell.)

The built-in exception to the rule is Kenny, who seems to have wandered in from ’Grange Hill’. Not just the only black one, he’s presented as more streetwise - seen on first appearance being cheeky to a policeman. We see both his and John’s bedrooms in the same episode, John with astronauts adorning his wall and Kenny footballers. Except… oh my God, they sidelined Kenny. This was mostly to do with the poor performance of the young actor, but still doesn’t help much.

’Tomorrow People’ was broadcast on ITV, Britain’s commercial channel, which at the time many middle class households still stuffily refused to watch. But it was one of ITVs more BBC-ish shows, effectively ’Blue Peter’ with telepathy instead of badges. John could have been a presenter, jaunting from one part of the studio to the next. He just needed a dog. It offered the uncanny on a weekly basis, only to serve up the cosy. (Sample Line: “Some sort of order had to be enforced.”)

You could, however, overstate the differences. There’s a parity of powers among the X-Men, in a way there wasn’t with other super-teams. (From the off, the Avengers featured both the mighty Thor and the winsome Wasp.) And there’s an emphasis on them fighting together, as a team, rather than just alongside one another. As demonstrated in… you guessed it, their first issue when they fight Magneto.

Plus, even if she’s relegated to the back of the first issue cover, Marvel Girl was set up as one of the stronger female characters of the era. The boys’ school reaction to her (essentially “yikes a gal” ) is best consigned to the past, particularly when their spying on her is played for laughs. Yet she’s presented both as powerful and as composed by nature, insisting “I’m not exactly helpless, as you can see.” (Or see the sequence below.) And the Marvel universe often took powers as manifestations of personality. (And she raised the bar. In ’Fantastic Four' 22, Jan ’64, the Invisible Girl’s powers were beefed up essentially by copying Jean’s, just with “psychic” relabelled as “invisible”.)

So, despite their major differences, both series leant heavily into psi powers. And indeed this was part of a general growing interest in such phenomenon through much of the Sixties and Seventies. Both hint heavily these come about through modernity itself. As mentioned last time, ’X-Men’ gestures at atomic radiation. Whereas the opening sequence of ’Tomorrow People’ shows Stephen ‘breaking out’ into his powers via almost breaking down, beset by a cacophony of thought voices in busy central London.

Ostensibly they just trigger, rather than cause, his change. But you can’t imagine the same event in reaction to a Seventeenth century hamlet. There’s the subliminal association of all those voices with mass media broadcasts, reminiscent of the line in the Hawkwind song ’Psi Powers’: “It’s like a radio you can’t switch off.” And the celebrated title sequence, a series of objects flying out at the viewer, could be said to represent the hurtling pace of modernity.

The trope’s often explained by referring to a equally growing interest in anti-materialist New Age claptrap about the Age of Aquarius. And in the first TP story their antagonist Jedikiah poses as a New Age guru. This was a time when the the pseudo-science of parapsychology was taken surprisingly seriously. The interest wasn’t just confined to popular culture but extended to official research. Even the CIA were getting in on it! ’Tomorrow People’, for its part, boasted in its credits of a scientific advisor!

But these all seem not causes but mutually occurring symptoms, coalescing around something else. Unlike the New Agers, we need to find something more material…

The first microchip was made in ’59, though as ever it took a few years to establish its existence. Which signified a wider change, where buttons to press slowly replaced levers to pull. It’s one of the classic transformative devices to be almost entirely unanticipated by the prophecies of science fiction, which carried on blithely believing better always meant bigger.

But once that rule was broken technologically, a ripple effect reached the human. Perhaps future generations might not need biceps to shift the couch or vocal cords to call across rooms, maybe they’d be able to do all it just by thinking hard. It worked in the same way that x-ray and radio technology had in their day stimulated an interest in mediums, by popular association. And it created an era where mind seemed to trump matter.

Conceivably this also lead to the trope of the computer as character. It’s hard to precisely pin this one down as it overlaps so much with the talking computer, which just receives and confirms orders out loud. But Zen in ’Blake’s Seven’ (1978/81) was even made one of the titular band. And the “biological computer” Tim, still more than Zen, is very much a character, one of the gang.

But how, I hear you ask, do these two scenarios play out in terms of stories? Tell you what, let’s look at that next time…

Saturday, 19 February 2022

FROM MONSTERS TO MUTANTS: X-MEN VS. THE FANTASTIC FOUR

In this first part of our new series Mutants Are Our Future, we hold up the first issues of ‘Uncanny X-Men’ and ‘The Fantastic Four’, the better to compare monsters to mutants

”It Ain’t Human!”

Mutants, when did they change? When did they stop being scary distortions of human form, who hung about in forbidden zones with backwards Rs on their signs and especially hankered after half-dressed blondes? In the 1955 film ’This Island Earth’, for example, ‘Mutant’ is really just science fiction for monster. So when did these monsters switch to become the next step in human evolution? Which turned out to be developing super-powers while wearing flashy latex.

A significant part of that shift was Sixties Marvel comics. In fact it started with one title - ‘The Uncanny X-Men’, debuting in 1963. I often find people insisting that this was the point where superhero comics hit on a potent metaphor for racism. But as we’ll see the reverse is closer to the truth.

’X-Men’ 1 came with the cover catchphrase “in the sensational Fantastic Four style”. It was the second Marvel super-team to be cut from whole cloth (‘The Avengers’ having been assembled from existing characters) and unsurprisingly cribbed from its 1961 predecessor. (In at least one account of events, publisher Martin Goodman noted the FF was selling and told his charges “do another one”.)

Reed Richards is essentially split into two characters, Professor X and Cyclops, the brainiac boss and the sober-minded field leader. While the feuding horseplay between Ben Grimm and the Johnny Storm is transferred to Hank McCoy and Bobby Drake. Bobby, like Johnny, is the youngest team member. The fire-powered one is replaced with Iceman, like that reversal of elements might be enough to conceal the copy. In a similar vein, McCoy’s Beast would later name-defyingly spout thesauruses in his speech balloons. But they hadn’t come up with that yet, so here he even sounds like the Thing. (His first line is “leggo my arm, you blasted walking icicle.”)

And the books start out structurally similar. The Hulk begins with Bruce Banner, and we go on see how he became big and green. Spider-Man starts with Peter Parker in High School, Thor with Dr. Donald Blake and so on. But with both the FF and the X-Men we’re thrown straight into the action. It’s as if we just walked up to Xavier’s school window and peeped in. Characters and concepts don’t get introduced like on your first day at work, they just appear and leave you to catch up.

It’s a more common way to introduce villains than heroes, for them to rear up at us for shock value. In fact it’s just the way Magneto gets introduced, later in this same issue.

Though the reason for this probably differed. The FF were the first Marvel book, with no norms established, so trying to draw in the reader with a baiting opening was a virtue found in a necessity. And the X-Men couldn’t start with their origins because… well, they didn’t have any. As Marvel’s first mutants, their super-powers just manifested. (Lee later confessed he’d chiefly come up with the notion so he didn’t need to concoct a new origin story each time.)

But these similarities just shows up deeper differences between them. We see the FF become the Fantastic Four separately, each individually set against the great American public. We see the X-Men assemble in their school, and go through their motions. In short the first time we see the FF the thing that’s stressed is their effect upon humans. And with the X-Men it’s their team bond. Like the FF the X-Men are an honorary family. Yet as we get to witness, the FF knew each other before the ill-fated rocket expedition. The X-Men come together precisely because of their mutant status.

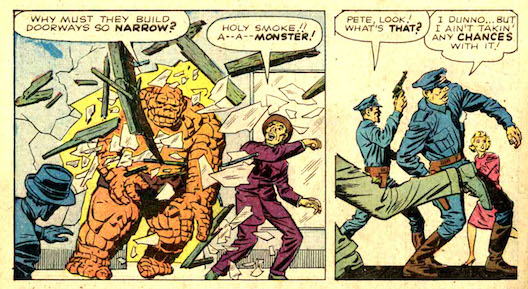

And the first public reaction to the FF is not the admiring public watching Superman perform a fly-by. Its horror and fear, the reaction to monsters. Let’s focus on the Thing who, alongside the Hulk, was the most monstrous Marvel hero. As he smashes his way out of a shop doorway (leaving you wondering how he ever got in), someone cries “Holy smoke!! A - a - monster!” and a cop starts shooting. Later someone adds “It ain’t human!”

Though it’s hard to think back to this now, for the original readership this was their first sight of the Thing. Their reactions would have been much the same as the characters in the story. Not “here’s our hero”, but “a - a - a monster!”

Superheroes might transform their appearance, like Captain Marvel. Essentially Johnny Storm does this with his “flame on!” But Ben Grimm is stuck as this feared monster. Later stories featured Reed’s perpetual attempts to cure him, which (spoilers) always prove short-lived.

In fact the one person the Thing seems to have something in common with here is the villain, the Mole Man. Whose lumpen looks have led to him being shunned by society, hiding out underground with other monsters for companions, like it’s the world’s basement. “Even this loneliness”, he concludes, “is better than the cruelty of my fellow men.” The monsters he (somehow) commands are probably best understood as ‘Forbidden Planet’-style projections of his rage. The story ends with his death (no, honest) and Reed concluding “there was no place for him in our world.” Takes one to know one, you can’t help thinking.

Both comic books were created by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee. (Let’s not get into who did what right now.) Who were but two of many comic artists of their day to be Jewish. Lee was younger but both had been through the Thirties and Forties, so would inevitably have come across a great deal of anti-semitic propaganda - where people like you were effectively monsterised. Just consider that a sec. You’re not just thinking “that’s offensive”. You’re thinking “this is how others see me.”

Then, add the Civil Rights era. It’s true that the racist image of ‘The Jew’ was different, possibly even opposite, to that of ‘The Black’. Associated with usury, ‘The Jew’ is not a real man who lives by honest labour. Kafka’s phrase "damned loathsome thing” perhaps sums this up. Whereas, stemming from slavery and still associated with heavy labour, the problem with ‘The Black’ was that he was *too* manly. He was required for his supposed size and strength, but feared for it in equal measure. But direct experience of racism naturally lent them to sympathise with other such victims.

Next, happenstance. This monsterisation went alongside an industry predilection for monster stories, not least at Marvel. (Thing and Hulk were names both already used for monster stories before their now-better-known versions.) So, feared and shunned for their size and strength, the Thing and Hulk become associated with the ‘super-predator’ fears of anti-black racism.

In some ways between the social groups of white and black, they are able to articulate the white man’s fear of becoming, and being treated as, black. It’s similar to John Howard Griffin’s 1961 book ‘Black like Me’, a white journalist’s account of travelling through the segregated South as black. (Which was filmed in '64, and generated so much hostility he later moved his family to Mexico.) Interestingly this device echoes the earlier film ‘Gentleman’s Agreement’ (1947), where Gregory Peck plays a white journalist who poses as Jewish.

It’s an incomplete metaphor, of course. The most widespread and pernicious form of racism, structural racism, is bypassed to (yet again) individualise the problem. And our modern sensibilities want to ask why, instead of getting a white journalist to essentially black up, to know what being black or Jewish feels like - why not just get someone to tell us who’s… you know… black or Jewish?

But it captures something of how racism feels, from creators who had themselves experienced racism. And it does it juxtapositionally - it’s about having monsterisation thrust upon you.

(And as times went on even white-bread DC comics got in on the act. In 1970, issue 106 of ‘Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane’ was titled ‘I am Curious (Black)', where she declares “it’s important that I live the next 24 hours as a black woman.”)

”Got to Make Way”

So, how do mutants differ? In the first X-Men film, released in 2000, Professor X spells out the concept:

“Mutation, it is the key to our evolution. It is how we have evolved from a single-celled organism into the dominant species on the planet. This process is slow, normally taking thousands and thousands of years. But every few hundred millennia, evolution leaps forward.”

Though back in ’X-Men’ 1, Lee has still not entirely given up on his belief in the transformative properties of radiation. Here the great Professor says “I was born of parents who had worked on the first A bomb project…. I am a mutant… possibly the first.” Lee had previously loaded the Marvel universe with the stuff, springing up like whack-a-mole, always a flying canister or glowing spider for the unfortunate to run into. He now declares it all-pervasive. Functionally, of course, it’s still magic pixie dust mislabelled as science. Yet that upping of the ante makes a difference.

In ’The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction’, Paul A Carter points out “the nuclear bombs of 1945 inspired swarms of stories about radiation-induced human mutation, taking place no longer in race isolation... but in populations large enough to constitute substantial colonies. Authors could address themselves to the question of how such societies might function internally.”

And we see a version of that here. The Fantastic Four had stumbled into their super-powers, but by boarding the space rocket they had already chosen adventure. The X-Men, conversely, were simply born into changing times. Innate outsiders, they must build their own world. (Though the outsider schtick was at this point unevenly applied. In the second issue, the Angel’s held up from a mission by a mob of adoring girl fans, as if there was X-Mania afoot.)

Except there’s more… The formula is - radiation catalyses mutation, which in turn catalyses evolution. Evolutionary biologists are most likely sighing loudly at this point. But what concerns us here is the fictional applications. Popular culture tends to assume that evolution is teleological, that it’s essentially creation but without the God bit. Perhaps working more slowly but still towards some end-goal. Mutation then is evolution freed to speed up.

’X-Men’ 1 uses the term ‘homo superior’ once only. But that may have been enough to let the cat out of the bag. Because it goes on to be proclaimed quite openly as the trope advances, and particularly in popular song. There was Bowies ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ (1971):

“Homo sapiens have outgrown their use

“Let me make it plain

“You gotta make way for the homo superior.”

Radio Birdman then upped the ante still further with ‘New Race’ (1977):

“There’s gonna be a new race

“Kids are gonna start it up

“We’re all gonna mutate

“Kids are saying yeah hup”

(Everyone got that? “Yeah hup.”)

And what does this do but confirm the obsession of the most hardline racist - the ‘great replacement’ theory? Why are other people black or Jewish? Clearly to conspire against you and me!

Which is what makes mutation the single worst metaphor for racism. In racist conspiracy theories Jewish people are already in essence super-villains - masterful, elaborate schemers, secretly in control of everything. And not just more folk holding down regular jobs, like they actually are. Whether heroes or villains, mutants… well, they quite clearly are different to you and me. The X-Men’s Magneto was retconned as Jewish. Out of the Jewish people I know, not many can bend metal with their mind…

(Perhaps most bizarrely, as the series progressed Professor X’s mind control powers were more and more employed. Though more than once he’s wheeled out as a deus ex machina device, mostly they’re used to re-establish plot stasis; at each issue’s end he’ll wipe the memories of those who’ve learnt of the X-Men’s existence. Which seems to skate remarkably close to anti-semitic tropes about the seemingly physically weak who manipulate their world, conceits about the “Jewish-controlled media” and all the rest.)

But what’s a lie about race is a self-evident truth about age. One generation does replace another. And what was the other great sociological event of the Sixties, alongside the Bomb and Civil Rights, but the generation gap? Which proved perhaps more rupturing. Adults aren’t just party poopers, telling you you can’t use the car cause you didn’t work late. Now, in Dylan’s words, “Your old road is rapidly agin’/ Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend a hand.” When Prof X. says “there are many mutants walking the earth… and more are born each year!” it presages the later hippie saying “there’s more of us being born and more of them dying.”

Most people work out sooner rather than later that ‘breaking out’, as it’s called on the (upcoming) ‘Tomorrow People’, where your powers suddenly manifest unexpected and inexplicable transformation, is a metaphor for puberty. And like mutation puberty feels like evolution speeded up. Physical changes such as growth seem to happen frustratingly slowly to the young child. Then with puberty it’s like you were suddenly zapped.

(Though it’s also possible to overstate the significance of this. I certainly bought into the concept of the Tomorrow People, to the point where I’d keep watching an average-at-best show, long before puberty. And the most puberty-related character of classic Marvel was not a mutant but Spider-Man, again often beloved by young children.)

”The Day of the Mutants”

The opening line, “in the main study of an exclusive private school”, makes the whole thing seem about as cosy as Harry Potter going to Hogwarts. The Angel seems to be identified as the posh one to stop us noticing they’re all the posh one. Yet noticeably, at this stage these teens are very much teens. They’re regular kids who happen to have powers, indulging in horseplay and (not the issue’s most edifying moment) going ga-ga over Marvel Girl’s arrival.

The cerebral nerds and band of outlaws comes later. (And Kirby in particular, having a rough blue-collar upbringing on the Lower East Side, would have had little inclination to identify with them.) Perhaps it’s just hard to unsee. But it still seems inexorable. This is a path that leads to ‘the geeks will inherit the Earth’. As Richard Reynolds has said: “Much of the appeal and draw of the mutants that comprise the X-Men has to do with feeling like an outcast while simultaneously feeling like part of a family.”

Many monster stories throw in a switch by showing us a horrific creature then asking us to identify with it. Mutant stories presuppose that identification. Because we’re primed to see ourselves as the special one. First, to the racist mind, whiteness is considered a form of evolution in itself. Blackness is associated with Africa, with primitivism, whiteness which progress. Science fiction often fetishises whiteness as an aesthetic. To this mentality, whiteness is already a mutation, a signifier of improvement.

Comic fans, commonly white and from comfortable backgrounds, can identify with this more than most. And inasmuch as it works as a form of anti-racism, it’s not one where white folks renege on their privilege. It’s one where we assume we will naturally use our special powers for the greater good, such is our benevolence. Black folks are still held to be not as smart as us but that’s why we should take it on ourselves to look after them anyway. It’s a means by which we can feel simultaneously superior and virtuous.

Perhaps because they’re neither teens nor nerds, Kirby and Lee seem to see this problem. And their solution is to acknowledge it by externalising it. Enter the X-Men’s foe, Magneto, exemplifier of “the evil mutants”. “The human race no longer deserves dominion over the planet earth!” he monologues. “The day of the mutants is upon us!” Unlike the Mole Man, nothing happens within the first story to contextualise his stance or make it even semi-sympathetic. He’s just like that, in the same way the X-Men are just not like that.

The FF’s first reaction to their powers is to get into an acrimonious fight, then place their hands together in a pledge. The X-Men fight too, but in what’s emphasised to be no more than juvenile horseplay. All the negative stuff gets pushed onto Magneto.

But a side effect of this mechanism is to marginalise the regular humans. We’re told the reason for the secrecy round the school is their fear and distrust. But unlike FF 1 we never witness any of this. The only humans we encounter are, briefly, the US Army. Who quickly give this strange-looking team their blessing to take on Magneto.

Furthermore, unlike the Thing all of the X-Men can pass for human when they need to. Even his nearest double, the Beast. The ability of humans, already restricted in scope to fearing and shunning you, gets diminished further. Even the American army is the equivalent of the heroine in a Victorian melodrama, there to be rescued.

And if villains are normally the return of the repressed, the Mole Man was our fault. We were the ones who sent him into the exile from which he burst back out from, monsters in tow. Whereas in this closed loop Magneto exists solely to be the antithesis of their family group, the kid who plays nasty because he’s so used to playing alone. The relationship is quite close to International Rescue versus the Hood in ’Thunderbirds’. All you’d really need for a perfect match would be Magneto engineering the crisis to draw the X-Men out.

Of course you can’t always tell the flower by the roots. The FF had, after all, already changed quite considerably in the intervening couple of years before the X-Men’s first appearance. (Let alone later.) Read the two first issues together and you get such strange sights as the Thing not yet talking like the Thing, while the Beast does talk like the Thing! At one point Magneto skulkingly hides from the X-Men, hardly how he came to be.

Nevertheless, as soon as coined mutants were everywhere. With the aid of retconning. “I??”, asked the SubMariner in issue 6. “A mutant?? Why has that thought never occurred to me before?” Possibly for the same reason it’s never occurred to me. Because I’m not one.

But the clincher comes in issue 3, where the Blob first wobbles in. He’s told he’s a mutant by the X-Men, as they think this will lead him to join them. Instead he uses his new-found powers to fight them. Except… well, it’s not his powers that are new. He’s already using them in his circus act. It’s knowing the word, having the label to stick on himself, which makes the difference. “For years I thought I was just an extra-strong freak! But I found out what I really am! I’m a mutant! Understand? I’m one of homo-superior! And that means I’ll run this show from now on!” To which the only solution is Professor X getting him to forget the word again.

And so us regular folk are forever sidelined, dismissed by the Blob as “rubes”. Except of course we don’t see the humans as us at all. We see them as them, the semi-hysterical rabble in the street scenes, the nameless extras in our lives, but not our special li’l selves.

The X-Men’s introduction emphasises their otherness. But from there, first our interest, then our identification gravitates to the mutants. The fundamental premise, that this stuff is written not for the common herd but special people like you and me, may be less upfront but is there from the start. Issue 15 ended with the payoff “even if you’re not a mutant you mustn’t miss” the next instalment.

Coming Soon! Even if you’re not a mutant you mustn’t miss the next instalment, our comparison of the X-Men to the Tomorrow People…

Saturday, 2 November 2019

‘JOKER’

First with the Dark Knight series and now this, there’s something about Bat-family films which not just polarises audience responses but across political lines. (See my comments about’Dark Knight Rises’.) Except if anything, with political events being raised to a still shriller note in the intervening years, the debate has become even more acute.

The accusation it’s some kind of Incel manifesto is frankly bizarre, as that’s quite explicitly knocked down by the film. When Fleck finally acts on his crush over his neighbour, knocking on her door than immediately taking her in his arms, we groan at the cliché but we don’t question. After all, such scenes are so common in mainstream films we’re inured to them. So we’re wrongfooted when we later discover this unlikely tale was just a fiction he told himself.

And when she finds him in her apartment, confused between fact and fantasy, she finds him fearful but also pathetic. She asks if he needs her to call his Mother, as if he’s a child. Which is pretty much the way the film asks us to find him. He’s not a hero, some breaking-the-rules anti-hero or even an anti-villain but the Woobie.

So is Michah Uetricht right to claim that instead it’s a “warning against austerity”? There’s arguments for this. The path out of poverty doesn’t seem to be solidarity with those around you, but the carrot of celebrityhood. And this is clearly shown to be nothing but wish fulfilment. Fleck’s plans to be a comedian are doomed to fail, his mother asking him outright if that wouldn’t involve being funny, and his belief he’s Wayne’s son (a fairy-tale story of a lost prince) gets scuppered.

Yet there’s an obvious rejoinder. If you were attempting a timely critique of austerity you’d hardly set it in early Eighties New York. (Ostensibly it’s Gotham but every frame says New York and the three yuppies work in Wall Street.) It doesn’t just swipe from movies from that era it does so self-referentially, such as reprising the ‘shoots self’ mime from ‘Taxi Driver’. Yet when made ‘Taxi Driver’ was contemporary set, Times Square really looked like that. Here even the Warners logo is retro.

And we’re so used to seeing this on screen that it’s become Past As Foreign Country. Seventies/Eighties New York may even have become our default example of the Big Bad City – corrupt and crumbling yet compelling. Similarly the general prejudices exhibited, such as the mental illness stigma, can too easily be filed under Bad Old Days.

So it’s neither option? Yes, and deliberately so. The neighbour scene is one of many where something gets wrongfooted, so many the device must surely be intentional. We’re cued to expect some Jekyll-into-Hyde moment of transformation, but it doesn’t really come. Joker dances carefree on the same steps Fleck used to slog up, a striking image which made it onto both the trailer and the poster. But at what seems his greasepaint apotheosis the two investigating cops suddenly appear. For no good narrative reason. But they do get to chase him, taking you back to Fleck clumping after the kids in the opening scene.

Even in his TV studio appearance, there’s still signs of Fleck. (His audience engaging skills include thumbing through his notebook, then saying “here’s one”.) Arguably in the very final scene in Arkham the Joker persona is fully loaded. But that in itself suggests that Joker can’t appear in a film like this, that we’ve hit the point where we need to cut. Which is shrewd. Despite what some seem to think super-villains and real world settings don’t mix.

We have a central character who finds things inappropriately funny, exacerbated further by a condition which induces nervous laughter in him at inopportune times. And the film then projects all this onto us. Rather than press an agenda, it’s more interested in inviting responses then forcing us to question them.

Take the use of the dwarf character. When others make easy digs about his height, we figure they’re being outed as jerks. But when Fleck decides to spare him from a killing spree, he finds he can’t reach the latch on the door to escape. At which point the film manufactures a joke against him, and we’re forced to reassess our earlier responses. In a film where people are keen to find some kind of manifesto, it seems more interested in getting us to reassess ourselves.

But for all that Tony Keen is right to call it right wing. We’re being told “that grassroots anti-capitalist movements are far worse than capitalist rotten apples.” it’s just that this is the more common route of Hollywood films, less manifesto and more unconscious bias. Look at the way Fleck’s lack of a father figure leads to an imbalanced, unhealthy mother fixation and a consequent inability to socialise or respect authority. To ensure we don’t miss this point he’s given two potential surrogate Dads, Wayne Senior and Murray the chat show host. Penguin in ‘Gotham’ was similar, if played more as a gag.

And the view of the crowd is typical for Hollywood, scarcely different to the Nolan films. Pleasingly, Joker is their totem not leader. Even when freed, he parades for rather than directs them. Which dispels a major problem with Bane in ’Dark Knight Rises’. And the way they deliberately play into Wayne’s dismissal of them as “clowns” is appealing, and something I’ve seen done on actual demos. (For example banners reading ‘Rent-a-mob on Tour’.)

But we’re still talking the traditional cod-Freudian fear of “the mob”, where the mask of anonymity removes all sense of social obligation and makes men animals. (And they do seem to be all men.) They, as Frick describes it, “werewolf and go wild”. Separate workers from instruction and all they can do is destroy. Protest is at best a symptom of the failings of the system rather than a step towards a solution, and at worst the fire arriving after the frying pan gets upturned. And this of course allows us our cake-and –eat-it response, where we can exult in the fiery drama of a riot while getting to piously condemn it.

For a Batman film, it would be surprisingly easy to write out all the references to him. Arguably, you could do it just by removing the iconic parent shooting scene, Bruce becoming Batman is really just a byproduct of events here. We’ve seen before how emblematic heroes, who make themselves into a symbol of the struggle for justice, precede super-powers, the Scarlet Pimpernel before Superman.

And in recent years how that has been reversed out, the super powers kept but the symbol of goodness gone. Superheroes engage more and more in personal quests, which easily elide into grudge matches. To the point that, when a film such as ‘Wonder Woman’ didn’t do that, it seemed unusual. ’Joker’, even more than ’Gotham’, is the logical terminus of this. This is neoliberalism’s version of “cometh the hour, cometh the man”.

Of course writing Batman out entirely wouldn’t have happened, it would never have been green-lit by Accounts. And director Todd Phillips has been completely open about that being the deal. But if we were to indulge the Fleck-like fantasy this film would be improved.

Fleck and his workmates are, by and large, carnie folk. ‘Freaks’ forced to sell their own freakishness in order to survive. And if there’s something folk horror about that, it should be played up. Imagine if our story starts in legend even then. There’s been some intra-universe folk bogeyman, a variant of the Demon Clown trope. Whose reception has over time travelled from credulous belief into entertaining comic strips and other popular media, much in the way of Spring-heeled Jack.

In the comics he has been given some heroic antagonist who keeps him in check. Yet after the Subway murders people start to wonder if the legends are true after all, and their world now has Joker without Batman. Reading and internalising sensationalised newspaper reports, the fantasist Fleck starts to imagine he has been the Evil Clown all along - so may as well start acting like it. Which would make the ending less a foregone conclusion and more creatively ambiguous.

Labels:

Comics,

Film,

Politics,

Superheroes

Friday, 19 April 2019

‘TOVE JANSSON (1914-2001)’

Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

Tove Jansson is of course known to one and all as the writer and illustrator of the Moomin books. But this show tells us something previously unknown, at least to me, she “always considered herself primarily as a painter”. And, though her illustrations form part of the show, it has enough courage in this conviction not just to start off with her paintings but run them for the first few rooms.

Two paintings might map the course of this double career. In ’Self-Portrait’, (1937, above) she sits bold upright and alert, her angular features akin to her work, every inch an ambitious young artist. Completed still lives and portraits sit behind her, another still-life to her side ready to be painted and added to the oeuvre.

’The Graphic Artist’ (1975, above) continues the conceit of an artist who resembles their own work. But in every other way it’s entirely different. She’s hunched not over an easel but a drawing board, pen in hand. This time she doesn’t look up at us, not the assertive genius but the commercial artist always working, with no time for visitors. There’s less space given over to the room, with no window at all. The colours are more dark and deep than bright, while the works we see are dominated by black and white. The figure is largely defined by a bold black outline.

Jansson was Finnish (though Swedish-speaking), and in contravention to her work for children your first response is to indulge in Nordic stereotypes about Munch-like melancholia. In for example ‘After Party’ (1941, above) any actual party probably happened weeks ago. Most of the figures are arranged in couples, though one only has a dog. But rather than see them as dancing or snogging, they seem to facelessly cling together in empty space. One just gazes listlessly out the window.