“In an environment reverting to savagery it seemed that one must be prepared to behave more or less as a savage…”

Let’s look at this through a Q&A format…

So this novel is now infamous for pioneering the cosy catastrophe? What’s that?

By law, you cannot discuss John Wyndham’s 1951 novel without using the following Brian Aldiss quote, from ’Billion Year Spree’. I’m going to start off with it, just so I don’t get into any trouble.

“The essence of cosy catastrophe is that the hero should have a pretty good time (a girl, free suites at the Savoy, automobiles for the taking), while everyone else is dying off.”

But so many bad things happen! Bad things can’t be considered cosy.

This one comes up a lot. Yes, bad things happen. A blinded Doctor, realising his situation, asks to be directed to a window then jumps from it, before we’re mid-way through the first chapter. But at the same time post-catastrophe guests are still served “the best brandy”.

Because this objection is - to use the terminology of the day - piffle. ‘Cosy catastrophe’ is two words, and the genre aims not to repress but to exploit the oxymoron. Wyndham makes a point of using real place names throughout, down to specific London streets, each iteration evoking this disjunction.

Let’s look at this through a Q&A format…

So this novel is now infamous for pioneering the cosy catastrophe? What’s that?

By law, you cannot discuss John Wyndham’s 1951 novel without using the following Brian Aldiss quote, from ’Billion Year Spree’. I’m going to start off with it, just so I don’t get into any trouble.

“The essence of cosy catastrophe is that the hero should have a pretty good time (a girl, free suites at the Savoy, automobiles for the taking), while everyone else is dying off.”

But so many bad things happen! Bad things can’t be considered cosy.

This one comes up a lot. Yes, bad things happen. A blinded Doctor, realising his situation, asks to be directed to a window then jumps from it, before we’re mid-way through the first chapter. But at the same time post-catastrophe guests are still served “the best brandy”.

Because this objection is - to use the terminology of the day - piffle. ‘Cosy catastrophe’ is two words, and the genre aims not to repress but to exploit the oxymoron. Wyndham makes a point of using real place names throughout, down to specific London streets, each iteration evoking this disjunction.

Similarly, the cover of the 1979 Penguin edition is a remarkably akin to a still from the 1981 TV adaptation. (Widely considered the best.) The sinister plants rear menacingly before a reassuring suburban semi. (Dilapidated in the drawn version, perhaps harder to achieve in a real setting.)

The back cover blurb to the Sphere edition of John Christopher’s ’Death Of Grass’ talks of “civilized values… now as out of place as a dinner jacket is in a slaughter house.” Which may be the most cosy catastrophe passage ever written. Aldiss is using the term in a derogatory fashion, but I don’t think he’d deny any of this.

And our narrating hero Bill Masen exemplifies this. Having no real social ties and a knowledge of triffids, objectively speaking he’s well-placed for all this. As he says: “curiously what I found that I did feel - with a consciousness that it was against what I ought to be feeling - was release…”

So within that juxtaposition, upsides can exist. The rupture is such that some are able to swap their Burtons suits for fine dinner jackets, which they wouldn’t have got to wear any other way, so every cloud…

But Bill also tells us early on …

“This is a personal record. It involves a great deal that has vanished for ever, but I can’t tell it any other way than by using the words we used to use for those vanished things, so they have to stand.”

Now this is almost certainly Wyndham writing the only way he knew, about the only sort of person he knew. It wouldn’t be a huge leap of faith to suggest that he based Masen on himself. But this is just to describe what writers do, turn necessity into invention. And it does create opportunities….

We have precisely the wrong narrator to tell us this sort of thing. And that’s the point, that we understand the true horror of it all will be beyond his powers of description. We’ll only see their shadow. He writes in the inverse, for a future audience to who its our world which needs explaining. (In fact, had I been Wyndham’s editor, I’d have told him to promote that quote from the start of the second chapter and open the book with it.)

What else did Aldiss say?

Glad you asked. He also complained it was…

“…totally devoid of ideas but read smoothly, and this reached a maximum audience, who enjoy cosy disasters.”

Which, despite being the lesser-known quote, is if anything more vituperative. Presumably ‘walking killer plant’ is considered just a trope, the elements so borrowed mere plot mechanisms, and so on. The argument seems to be this is a novel which functions well, but no more. It’s been engineered rather than written, a prototype for mass production.

But ’no ideas’ rests on a somewhat narrow definition of ‘idea’. Yes, there’d been post-apocalypse stories before, but there’d been political dystopias before ’Nineteen Eighty-Four’. And it seems a strange critique for something so stuffed with ethical debates. One chapter, ’Conference’, is literally a formal ethical debate. Wyndham started writing for the pulps, but his style from hereon in was to intersperse dramatic action with pipe-puffing philosophy. His intent, at the very least, was to pack the book with ideas.

Well all of that’s as maybe but, ‘Day of The Triffids’, that’s all about fighting off triffids, surely?

Actually no. It would be cute to say that in the land of the blind, the deadly plant species is now king. But it would be more accurate to say that in the land of the blind people fall out a lot.

The triffids rarely intrude. Most die from disease. The survivors forget about them in between, and it's clear we readers are supposed to as well. They lurk around the edge of events, strike, and are gone again. If you struck out every scene that referred to them, the book wouldn’t be that much shorter and would still largely function. It might be less memorable, true. But it would still function.

Okay, not triffids then… wait, this being a Cold War novel - the meteor shower that makes almost everyone blind, that symbolises the bomb, right?

Nope.

Oh, its definitely a Cold War novel. The whole business of the triffids spreading worldwide comes from a botched attempt to smuggle them out of the Soviet Union, a mirror image of the way nuclear secrets were being smuggled West to East. A terrible disaster from which few survive unscathed, that scenario may have already been in use, but the Cold War certainly expedited it.

But the meteor shower would be a very shonky symbol for the Bomb. Of course, looking at a nuclear blast could strike you blind. But that has little to do with its representation in popular culture. Which were more to do with the Bomb instantly vaporising all and sundry. (Think for example of the 1950 Ray Bradbury short story ’There Will Come Soft Rains’, when an automated house keeps working while it’s inhabitants have long since become mere shadows on the wall.)

Besides, the whole point is the way people unknowingly flock to watch the meteors, like a kind of free firework show. It’s less a social disaster we bring upon ourselves, more a personalised disaster that each individual takes their own eyes to.

But most of all, the text brings up the comparison. In order to rule it out.

“From 6 August 1945 [the first bombing of Hiroshima], the margin of survival has narrowed appallingly. Indeed, two days ago it was narrower that it is at this moment… there might have been no survivors, there might possibly have been no planet. And now contrast our situation. The Earth is intact, un-scarred, still fruitful… we have the means, the health, and the strength to begin to build again.”

The whole novel is informed by the Cold War. It couldn’t have been written, at least not the way it is, in the Thirties. But ‘informed by’ is not the same thing as ‘about’.

Oh, for heaven’s sake, what is this novel about then?

Class war.

Come on Gavin, you say everything is about class war.

True. But this is very definitely about class war. A cosy kind of class war, as you might expect. But class war all the same. Rather than Aldiss, it would be better if the quote everyone knew was from John Brosnan in ’The Encyclopedia Of Science Fiction’:

“The atmosphere is rather too cosy; in fact [it] sometimes takes on aspects of a middle-class, rural paradise, what with the disappearance not only of all those smelly cities but also of the working classes.”

True, this may be because he’s not actually talking about ’Day Of the Triffids’, instead its the later TV series ’Survivors’. But it's equally applicable.

Here’s a sample of dialogue…

“‘Ere we are, gents one an’ all. Piccabloodydiddly Cirucs. The Centre of the World. The ‘Ub of the Universe. Where all the nobs had their wine, women and song.”

In fact so many ‘aitches are dropped in dialogue, you ‘alf wonder if Wyndham wore out the blinkin’ apostrophe key on his typewriter, guv. This is the head and (literally) the eyes of a rampaging mob speaking, unapologetically after booze and women. Without the good example set by their betters the proles become more prole-like, revert to drunken savagery.

Yet not all of them. Some make a moral argument. Coker insists that now eyes are in short supply they must be rationed out, each sighted person looking after a group of blind. Which contrasts with Doctor Vorless, insisting the only priority is that “the race is worth preserving.” (“Different environments set different standards…. The conditions which framed and taught us our standards have gone with it. Our needs are now different, and our aims must be different.”) And as Corker becomes a literal interlocutor between sighted and blind, so…

“His voice was a curious mixture of the rough and the educated so that it was hard to place him - as though neither style seemed quite natural to him, somehow.”

Vorless and Coker become like two Kings, standing certainly on either sides of the chessboard of London. Each is certain in his proclamations, while everyone else wanders about the board blindly. (Ironically, in the circumstances.)

It’s also noticeable that the two sides in this formal debate stay largely off-page. Coker only appears as a character after this debate has been resolved by events. He admits, in fact he re-appears largely to admit, he was wrong. Vorless, after delivering his set-piece speech, never reappears and never talks directly with Bill.

Is morality merely socially contingent, where new conditions will call for new forms of it to be devised? It’s arguable, to some degree or other. Yet one thing which can clearly exist only in a social context is class. That society collapses and it doesn’t much matter who was a milkman or a merchant banker yesterday. But this book turns this upside down, its conception of class is essentialist just as much as it’s sense of morality is relativist.

Further, while the proles can follow moral guidelines, it’s only the educated elite with their leadership role who must set them. The proles just continue to clutch a rule book that’s lost its relevance, while the educated elite write a new one.

And this confrontation resembles a lock-out, with the workers arguing they have a right to life so it follows they must have a right to work. Bill is later kidnapped and literally shackled to a party of blind people, who he must lead at the same time he’s their prisoner. There seems more than a slight critique of the Welfare state here. The 1942 Beveridge report had promised to slay five “giants”, Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. All but the last of these now reappear, as facts of life. The surplus proletarians must be allowed to perish.

Much is made of the lead characters having a head versus heart dilemma, wanting Coker to be right while knowing its Vorless. And it may be that, in these circumstances, Coker is wrong. In this situation there is nothing to be gained by prolonging the blinded’s misery.

But then the whole point of this elaborate set-up is to make Coker’s argument wrong, which feels a bit like loading the dice. What use will Supplementary Benefit be if the whole world gets blinded and then killer plants attack? Yeah, good point mate. Better watch out for that one.

And this is the bizarre thing - this formally so innovative novel was in its content not the start but the end of something. The 2005 BBC documentary states the book was begun on Valentine’s Day, 1949, which might seem suspiciously precise. But we do know it was first serialised from January 1951. The novel version then appeared in December that year.

Which was two months after a Tory electoral victory, from which they stayed in power for over a decade. But by that point they had come to accept the changes already made, leading to what was effectively a class truce. The proles agreed to stop rocking the boat so much, and in return the bosses agreed to better seating arrangements.

It’s arguable that times of social upheaval have a tendency to return to Wyndham. 1981 saw a TV version of ’Triffids’, and a radio adaptation of ’The Chrysalids’, followed by a TV version of the later ’Chocky’ in ’84. A period which marked the first term of another long-running Tory government, but this time one intent on tearing up that class truce.

But at the time a novel written on the perils of class war appeared just after a class truce had been called. The bourgeois fear of the immediate post-war years, that we were heading for some Stalinist system, where the Ministry of Tyranny would seize your family heirlooms in the name of the people, that did not transpire. The social fears it channels were already being submerged, as soon as it was published.

So what connection is made between the mass blindness and social class?

There isn’t. Its not referred to in the text in any way. In fact it flatly contradicts what we’re told about the meteors, “everybody’s out watching them.” But it’s there. Now and then we do run into someone posh but blind, so the diegetically unsupportable connection doesn’t seem too clear-cut.

There may be an underlying symbolic one, that we naturally divide between visionary leaders and dutiful followers waiting to hear fresh orders. But its latent at best.

But then what about the Christian camp?

Some claim this book to be a paean to right-wing individualism, the strong surviving by shunning the weak. Perhaps because later iterations of this genre did often overlap with survivalism. And it’s true that Robinson Crusoe, the fictional totem of that thinking, is once referred to.

But in fact Bill decides early it’s a situation you can only hope to live through by joining a group. And the end of civilization proves a handy opportunity for some social climbing. He tries to get with the proper toffs from the side, after seeing (and a chapter’s named after it) ’A Light In the Night’.

From an early point the book is structured as a series of attempts by Bill to find the community they’re founding, but with events conspiring to take him somewhere else. It’s repeatedly explained that it won’t be any kind of panacea even if he can get there, that life there will be harsh, that it may even fail, its just our best shot. Yet at the same time it occupies the same place as utopia often does in fiction, a deferred end goal, always around the next page. And he’s waylaid by first the working and then the middle classes.

True for much of this he’s more after his new-found girlfriend. But then how’s she first described?

“Her clothes, or the remains of them, were good quality. Her voice was good too [and] it had not deteriorated under stress… She looked as if she had strength [which] had most likely not been applied to anything more important than hitting balls, dancing, and, probably, restraining horses.”

She’s from St. Johns Wood. She’s such a society gal she missed the meteor shower by sleeping off a party. And she’s named Josella. I mean, Bill and Josella? Bill’s class climbing is mostly achieved by marrying into the family. And though she’s first encountered in a damsel-in-distress state, overall she adapts to the new normal better than him.

It’s also notable that, as Coker’s gang are limited by their lower class-ness, the Christian camp are led and dominated by women, and thereby beset by all that emotionalism they inevitably exude. They can’t hook the lights up because they don’t understand machines, so instead darn by candlelight. True, Josella is an exception to this. But then she’s a proper toff.

It’s quite surprising how much this conventional morality is specified as Christian. At least they insist on this, and no-one contradicts them. Which is close to saying Christianity now needs to be jettisoned, and (at least in the novel) that this point is unarguable even if people persist in arguing about it. Which must have seemed heady stuff back then.

But Wyndham doesn’t depict religion, at least organised religion, positively. He might well mark the point where the implications of Darwinism finally superseded a more static Christian morality. Notably, all three of his best-known books quite centrally feature evolution.

Okay, so what connection is made between the meteor storm and the triffids?

There isn’t. The triffids are already in place prior to the meteor storm. And throwing both into the mix does seem to be over-egging it. You’re half tempted to ask if the Loch Ness Monster showed up at the same time. And this is made somewhat worse by the association, where the Triffids strike to blind.

Adaptations, perhaps unsurprisingly, see this duality of the disasters as a plot hole to be filled in. The 1963 film, for example, has triffid spores arriving with the meteor shower. (Something explicitly ruled out in the book.) There’s also a fan theory that the triffids called it down, in some unspecified way. (Which, like many a fan theory, is baseless.)

But what this does in terms of tidying up the plot regularises the content, standardises everything. Much of the appeal is that no-one knows very much about the triffids, how smart they are, whether they can even communicate. As Josella says, “they’re so different!” And this unknowing adds to their menace. The triffids are there precisely so we can’t understand them, and much would be undone by saying more.

As Miles Link says: “The triffid is not simply the negative image of what bourgeois post-war life values: it does not merely connote collectivity rather than identity, or evolutionary shift rather than stability. Instead, the triffid cancels the order upon which those values are built.”

In other words, we cannot just attach our negative words to them, for we cannot attach any words to them. They’re beyond our terms of reference, and this is precisely what makes them horrific. (NB I don’t always agree with Link’s analysis, but do here.) This means Wyndham can’t place them centre stage and use them as he wants. So he doesn’t.

(Were I Wyndham’s editor I might have suggested the meteor storm somehow activated the triffids, making them mobile, more motivated, more poisonous or similar. I wasn’t Wyndham’s editor.)

However, if not an connection there is an association, which we’ll come onto later…

Okay, this being ‘Day Of the Triffids’, what do the triffids represent? Surely something!

There’s no shortage of theories, but few convincing ones. Aldiss again: “Either it was something to do with the collapse of the British Empire, or the back-to-the-land movement, or a general feeling that industrialisation had gone too far.”

Taking up the first of these, Jerry Maata has described them as “distorted metaphors for the colonised people of the British Empire, coming back to haunt mainland Britain much as the Martians did in Wells.”

The Wells comparison is odd. His Martians weren’t colonial subjects out for revenge but greater colonisers, bigger kids who came to pick on us just as we had the Tasmanians. Perhaps the idea is that the triffids are more like Zulus, seeming primitive push-overs who turn out to be tougher than they looked, speaking their own inscrutably private language. The analogy’s insulting, of course, but that scarcely seems a reason to deny it.

But Josella has already pointed out the flaw here. The triffids are too otherly, too de-anthropomorphised, for this to stick. It’s the same problem as explicitly granting them sentience. It doesn’t convey what they represent, it takes it away. You don’t gain stuff, you lose stuff.

Aldiss’ second and third suggestions really run together, and run into the other big theory, ’Nature’s revenge’. This might seem to be almost explicitly ruled out. We’re told “one could not even blame nature for them,” because they’re “the outcome of ingenious biological meddlings.” And yet… it’s suggested the meteor storm itself wasn’t the problem, but it striking a satellite containing some chemical weapon that causes blindness. Or later, that a satellite malfunctioned into disgorging it’s cargo, and everyone took it for a meteor storm.

And satellites were at this point science fiction, the first successful launch not until six years after publication. (Placing the book in an odd interchange where satellites and cinema newsreels coexist.) Wyndham has to explain to readers what they are. So what we have is a mixture of our hubris bringing us down, and nature getting pissed off with being meddled with and so meddling back.

“The countryside is having it’s revenge, all right… It rather frightens me. It’s as if everything were breaking out. Rejoicing that we’re finished, and that it’s free to go its own way.”

And the significant thing there it that it’s the countryside getting its own back, with the triffids just its strike force.

People today sometimes scoff at attempt to make plants scary, as if back then you could scare an audience with hydrangeas. And it is true that most of its inheritors went for zombies, seeking to up the scary stakes. As Aldiss (yes, back to him!) said “the catastrophe novel supposes that one starts from some kind of established order, and the feeling grew that even established orders were of the past.” The obvious example is ’28 Days Later’, which borrows heavily from the book in terms of form, but takes it mood more from ’Night Of the Living Dead’. Its classic quote is:

“This is what I've seen in the four weeks since infection: people killing people. Which is much what I saw in the four weeks before infection, and the four weeks before that, and before that, as far back as I care to remember - people killing people. Which, to my mind, puts us in a state of normality right now.”

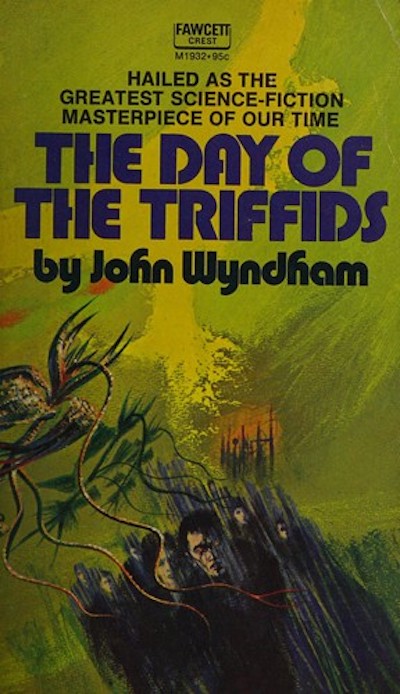

But was abandoning plant life a necessity? Making the triffids scary, that’s more a problem for the adaptations than the book itself. Wyndham refers to how the perambulating plants were first seen as comical, but came to be feared - a change more easily conveyed in print. Even the cover illos can struggle with this. The 1954 depiction isn’t just literally bollocks, the design suggests at it teaming up with the Penguin on the logo.

Some claim this book to be a paean to right-wing individualism, the strong surviving by shunning the weak. Perhaps because later iterations of this genre did often overlap with survivalism. And it’s true that Robinson Crusoe, the fictional totem of that thinking, is once referred to.

But in fact Bill decides early it’s a situation you can only hope to live through by joining a group. And the end of civilization proves a handy opportunity for some social climbing. He tries to get with the proper toffs from the side, after seeing (and a chapter’s named after it) ’A Light In the Night’.

From an early point the book is structured as a series of attempts by Bill to find the community they’re founding, but with events conspiring to take him somewhere else. It’s repeatedly explained that it won’t be any kind of panacea even if he can get there, that life there will be harsh, that it may even fail, its just our best shot. Yet at the same time it occupies the same place as utopia often does in fiction, a deferred end goal, always around the next page. And he’s waylaid by first the working and then the middle classes.

True for much of this he’s more after his new-found girlfriend. But then how’s she first described?

“Her clothes, or the remains of them, were good quality. Her voice was good too [and] it had not deteriorated under stress… She looked as if she had strength [which] had most likely not been applied to anything more important than hitting balls, dancing, and, probably, restraining horses.”

She’s from St. Johns Wood. She’s such a society gal she missed the meteor shower by sleeping off a party. And she’s named Josella. I mean, Bill and Josella? Bill’s class climbing is mostly achieved by marrying into the family. And though she’s first encountered in a damsel-in-distress state, overall she adapts to the new normal better than him.

It’s also notable that, as Coker’s gang are limited by their lower class-ness, the Christian camp are led and dominated by women, and thereby beset by all that emotionalism they inevitably exude. They can’t hook the lights up because they don’t understand machines, so instead darn by candlelight. True, Josella is an exception to this. But then she’s a proper toff.

It’s quite surprising how much this conventional morality is specified as Christian. At least they insist on this, and no-one contradicts them. Which is close to saying Christianity now needs to be jettisoned, and (at least in the novel) that this point is unarguable even if people persist in arguing about it. Which must have seemed heady stuff back then.

But Wyndham doesn’t depict religion, at least organised religion, positively. He might well mark the point where the implications of Darwinism finally superseded a more static Christian morality. Notably, all three of his best-known books quite centrally feature evolution.

Okay, so what connection is made between the meteor storm and the triffids?

There isn’t. The triffids are already in place prior to the meteor storm. And throwing both into the mix does seem to be over-egging it. You’re half tempted to ask if the Loch Ness Monster showed up at the same time. And this is made somewhat worse by the association, where the Triffids strike to blind.

Adaptations, perhaps unsurprisingly, see this duality of the disasters as a plot hole to be filled in. The 1963 film, for example, has triffid spores arriving with the meteor shower. (Something explicitly ruled out in the book.) There’s also a fan theory that the triffids called it down, in some unspecified way. (Which, like many a fan theory, is baseless.)

But what this does in terms of tidying up the plot regularises the content, standardises everything. Much of the appeal is that no-one knows very much about the triffids, how smart they are, whether they can even communicate. As Josella says, “they’re so different!” And this unknowing adds to their menace. The triffids are there precisely so we can’t understand them, and much would be undone by saying more.

As Miles Link says: “The triffid is not simply the negative image of what bourgeois post-war life values: it does not merely connote collectivity rather than identity, or evolutionary shift rather than stability. Instead, the triffid cancels the order upon which those values are built.”

In other words, we cannot just attach our negative words to them, for we cannot attach any words to them. They’re beyond our terms of reference, and this is precisely what makes them horrific. (NB I don’t always agree with Link’s analysis, but do here.) This means Wyndham can’t place them centre stage and use them as he wants. So he doesn’t.

(Were I Wyndham’s editor I might have suggested the meteor storm somehow activated the triffids, making them mobile, more motivated, more poisonous or similar. I wasn’t Wyndham’s editor.)

However, if not an connection there is an association, which we’ll come onto later…

Okay, this being ‘Day Of the Triffids’, what do the triffids represent? Surely something!

There’s no shortage of theories, but few convincing ones. Aldiss again: “Either it was something to do with the collapse of the British Empire, or the back-to-the-land movement, or a general feeling that industrialisation had gone too far.”

Taking up the first of these, Jerry Maata has described them as “distorted metaphors for the colonised people of the British Empire, coming back to haunt mainland Britain much as the Martians did in Wells.”

The Wells comparison is odd. His Martians weren’t colonial subjects out for revenge but greater colonisers, bigger kids who came to pick on us just as we had the Tasmanians. Perhaps the idea is that the triffids are more like Zulus, seeming primitive push-overs who turn out to be tougher than they looked, speaking their own inscrutably private language. The analogy’s insulting, of course, but that scarcely seems a reason to deny it.

But Josella has already pointed out the flaw here. The triffids are too otherly, too de-anthropomorphised, for this to stick. It’s the same problem as explicitly granting them sentience. It doesn’t convey what they represent, it takes it away. You don’t gain stuff, you lose stuff.

Aldiss’ second and third suggestions really run together, and run into the other big theory, ’Nature’s revenge’. This might seem to be almost explicitly ruled out. We’re told “one could not even blame nature for them,” because they’re “the outcome of ingenious biological meddlings.” And yet… it’s suggested the meteor storm itself wasn’t the problem, but it striking a satellite containing some chemical weapon that causes blindness. Or later, that a satellite malfunctioned into disgorging it’s cargo, and everyone took it for a meteor storm.

And satellites were at this point science fiction, the first successful launch not until six years after publication. (Placing the book in an odd interchange where satellites and cinema newsreels coexist.) Wyndham has to explain to readers what they are. So what we have is a mixture of our hubris bringing us down, and nature getting pissed off with being meddled with and so meddling back.

“The countryside is having it’s revenge, all right… It rather frightens me. It’s as if everything were breaking out. Rejoicing that we’re finished, and that it’s free to go its own way.”

And the significant thing there it that it’s the countryside getting its own back, with the triffids just its strike force.

People today sometimes scoff at attempt to make plants scary, as if back then you could scare an audience with hydrangeas. And it is true that most of its inheritors went for zombies, seeking to up the scary stakes. As Aldiss (yes, back to him!) said “the catastrophe novel supposes that one starts from some kind of established order, and the feeling grew that even established orders were of the past.” The obvious example is ’28 Days Later’, which borrows heavily from the book in terms of form, but takes it mood more from ’Night Of the Living Dead’. Its classic quote is:

“This is what I've seen in the four weeks since infection: people killing people. Which is much what I saw in the four weeks before infection, and the four weeks before that, and before that, as far back as I care to remember - people killing people. Which, to my mind, puts us in a state of normality right now.”

But was abandoning plant life a necessity? Making the triffids scary, that’s more a problem for the adaptations than the book itself. Wyndham refers to how the perambulating plants were first seen as comical, but came to be feared - a change more easily conveyed in print. Even the cover illos can struggle with this. The 1954 depiction isn’t just literally bollocks, the design suggests at it teaming up with the Penguin on the logo.

However, when Wyndham perambulated plants he also stuck a snake in them. He calls it a whorl, but it’s effectively the same. Like snakes, they’re slow to move but quick to rear and strike. Which is just the way some illustrators depict them, such as the Eighties edition below. (See a gallery of Triffid covers here.)

Mostly this objection suggests that we spend less time with plants today than people used to. Wyndham’s original inspiration was walking down a country lane in near-dark, sided by looming hedges. And it’s true up to today that our life on earth is only through nature’s sufferance. There are actual plants aplenty which are poisonous to touch. The one thing they can’t do is walk. But weeds can grow like wildfire, so fast it seems they’re effectively moving, taking over space as soon as your back’s turned.

Take the 1971 Genesis track ’Return of the Giant Hogweed’, which clearly riffs on the triffid trope, but is based on a real-life plant which genuinely came from Russia, genuinely came to be invasive and is genuinely toxic to us. The lyrics, especially when married to the martial-style music, suggest the plants are mobile without ever explicitly confirming it. (“Botanical creature stirs! Seeking revenge…”)

The novel describes how the triffids can withstand extensive damage, like trees. And in this way it may have been prescient. Just when we thought we had nature on the run, that would be time for it to strike. Don’t take your eye off the back garden just yet…

Coming soon! After this brief digression into other things Wyndham, back to the Pariah Elites…

If Triffids is about Class War or about Nature’s Revenge, there are two less well known novels to include for comparison. For Class War see also Nevil Shute’s very odd book about a socialist revolution having succeeded in the UK - the Royal Family end up wandering the world on a non-stop plane flight that needs refuelling in mid air, and only certain Commonwealth countries still support them. For Nature Fights Back, check out also Susan Cooper’s odd science fiction story Mandrake where the earth very literally fights back and wins the war of hearts and minds. (Jenni S)

ReplyDeleteI've not read either of those. (Mmm, Google still not allowing me to sign in to comment on my own blog. Happy times!)

ReplyDelete