“The mind is the reality. You are what you think.”

Tellin’ it Straight

Science fiction fans often dismiss modern literature as the Emperor’s New Clothes, fancy prose which conceals the lack of any actual substance. Whereas their genre, they contend, is unafraid to speak plainly because it has something to actually say. Like all stopped clocks, this one’s right at times and wrong at others. But it may strike right with Alfred Bester.

Not unusually for an SF author, he wasn’t writing character studies so much as thought experiments carried out under controlled conditions. The characters are more like elements introduced to the experiment to see how they react, and only need developing as far as the experiment requires.

More unusually for an SF author, he knew he was doing this. So the style he adopts isn’t heightened and dramatic but breezy and conversational. If van Vogt is like a sports commentator turned novelist, Bester is like someone who slid onto a barstool in some old-style dive bar on the Lower East Side, and told you a yarn. He isn’t going to start out by telling you that for centuries man has yearned to tread between the stars. He’s more likely to tell you that there was this guy who really wanted to stay faithful to his wife, but you know how it is…

’The Demolished Man’ (1953), is widely seen as one of his best works. While van Vogt’s ’Slan’ bagged a Hugo retrospectively, this was the first Hugo winner ever! The books are written barely more than a decade apart, and were both originally serialised in pulp mags. But one grew out of those roots…

You could recommend ’Slan’ to a classic SF fan, and probably be thanked. It’s effectively precision-honed for them, but that achievement leaves it less likely to appeal to anyone outside their bracket. ’Demolished Man’, though quite definitely SF and not just a detective story set in the future, is more something you could show to an open-minded reader.

Telepathy As Typography

Paul A Carter wrote ”space opera of the kind ‘Doc’ Smith wrote… tended to treat psi power as just another gadget, like the ray gun. There was some rudimentary discussion of the ethical implications… does it invade privacy, and so on. But EE Smith’s conclusion on this matter was not very different from what J Edgar Hoover’s might have been.” (‘The Creation of Tomorrow’) All that thrilling SF stuff is really just familiar things resized and relabelled, sailboats become spaceships, revolvers turn into ray guns and so on.

And Bester plays with this. Characters catch “the ten o’clock rocket to Venus” the same way we might flights, routine for the world they’re in. But mostly he throws psi powers like its a googly ball, plunging through society and affecting it in unexpected ways.

But there’s an anomaly. He isn’t one of those writers who gives you a neat future chronology in the back of the book, a route map of here to there. Instead he gives us snapshots of his future society, some of which are quite vivid. But they’re fleeting, like passing views out the foreground action’s window. You couldn’t stitch them into anything coherent.

Some see this as a deficiency. But we should read Bester as he asks to be read. Which means focusing on what he focuses on. His interest isn’t outer but inner, in what’s going on in the minds of his cast, what makes the experiment do what it does. He effectively thinks like an Esper, even if he isn’t one.

The scenario is that in the future the existence of Espers (telepaths) make murder impossible, but someone tries anyway. Espers aren’t arising, like we’ve see them up to now, but already integrated into society. Or as much as they’re ever likely to get. There are those who mistrust them, but at the same time corporations strive to hire the more powerful ones.

Their abilities have not led them to become morally more advanced, something ’The Tomorrow People’ took as read. Instead they’re run by a Guild, who impose an Espers Code, rigidly applied if never actually spelt out. Less the ’Tomorrow People’ Prime Barrier and more akin to professional ethics. Transgressors are ruthlessly drummed out. Within that, there are different Espers, with different motivations, just as with any other kind of person.

They’re a hierarchy, a strict tripartite system assigned according to power levels. But their hierarchy is Calvinistically unrelated to the surrounding society’s. The scene where only a “young negro” passes their test feels a little wince-inducing today, but was clearly intended as progressive at the time.

(Someone, somewhere has probably studied the degree of racism in early SF fandom. And that person isn’t me. I’d suspect most fans simply didn’t think about it very much, any more than anyone else did. After all, social conventions of the day served to keep white and black folks apart, and not just in the formally segregated South. And what views there were, there’s no reason to think they were either monolithic or consistent. There was always a tendency in SF to look forward to a future that was more advanced, so naturally had fewer of those ‘primitive’ blacks in it. But there is evidence to suggest that what few black fans there were became part of the group, that they were seen as fellow fans first.)

The first telepathic conversation we come across is between two workers, using their abilities to talk before their boss without him hearing. But the next is an Esper party, presented typographically, words running down the page, and this goes on to be the model. How much this works and how much it just resembles word puzzles is an open question, but it’s a bolder attempt than anything we’ve seen so far. (Though they’re rarely presented as stream-of-consciousness, surely an inherent feature of thought.)

We also learn that, logically enough, Espers also communicate by transmitting symbols. Characters’ names can incorporate these, Akins becomes @kins, Quatermaine 1/4maine and so on. Neologisms abound, such as “clever up”. This isn’t strictly Esper-related, these terms are used in general. But it adds to the overall picture. And all this is partly made palatable by Bester’s clear and direct prose. Mostly smooth sailing, every now and again we come up against something which takes a bit more digesting.

(It’s also bizarre how proto-modern how much of this feels, even if none of us have become telepaths yet. The random order of communications resembles message boards, the abbreviated style txtmsging, the symbols emoticons and Memes.)

That party’s thrown by the detective of the tale, Powell. And this is how he’s introduced:

“Like all upper-grade Espers, Lincoln Powell. Ph.D.1 lived in a private house. It was not a question of conspicuous consumption, but rather a problem of privacy… There were no servants in the house. Like most upper-grade Espers, Powell required large quantities of solitude.”

In short, Espers are introverts, like the stereotypical SF reader. But they have the super-powered ability to do precisely what that reader often struggles with - read people. Added to which, the variegated Esper classes more accurate reflect fan hierarchy than the blissful egalitarianism of ’Tomorrow People’. Fans even had handy acronyms for all this, FIAWOL (Fandom Is a Way of Life), FIJAGH (Fandom Is Just A Goddamn hobby) and so on.

A Mind For Murder

The business mogul Reich is compelled to commit the murder, which Powell investigates. So this is not a whodunnit but a howdunnit. For which there’s two general models. Let’s look at each in turn, and see how well this fits.

The first is a caper movie. In which the balance of power is always against the jewel thief (it’s normally a jewel thief), who has to beat all the security devices armed with zip wires and their own ingenuity. We watch them smartly win out over a situation stacked against them, encountering and overcoming unexpected obstacles. Formally it’s the opposite scenario to an escapologist slipping their chains. But it feels similar. We naturally side with them, the human element winning out over the mechanism. So Reich’s a social over-dog put in a situation which makes him the under-dog.

But it’s also remarkably like ’Columbo’. We watch the murderer carry out the crime, then the detective later arrive, fix on the killer straight away and over the ensuing narrative struggle to pin him. Here the balance of power seems to lie with the killer, the smart well-connected individual, not the crumpled little Lieutenant. The fun lies in watching this balance shift, them starting out with the arrogant assumption they couldn’t do something so common or lowly as to get caught, only to have that eroded.

Plus we see Powell take up other tropes which clever up the reader into following the investigator. As is often, his badge of office gives him access to all levels of society, from the “fashionable corruption” of upper-echelon parties to squatted slums.

And at times Bester seems to not just spot but exploit this paradoxical state. Later chapters don’t just shift between Reich and Powell but take on their perspective. We see things through Reich’s eyes, so when Powell does stuff it happens off-stage and we don’t find out about it until Reich does. Then we swap, and it’s vice versa. An unusual structure for genre fiction. At one point Reich commits a second murder, dresses it up as an accident, goes to hospital, escapes and goes on space safari - all off stage.

It’s also stated quite explicitly that the two respect… to a degree even like one another, and look forward to working together. Reich tells Powell: “We don’t play girl’s rules. We play for keeps, both of us. It’s the cowards and weaklings and sore losers who hide behind rules and fair play… We’ve got honour in us but it’s our own code - not the make-believe rules some frightened little man wrote for the rest of the frightened little men.”

But overall, Reich dominates. In ’Columbo’ the original murder scene is brief, we find out most of the details by following our dogged Lieutenant. After that early party scene for Powell, which seems more concerned with introducing us to Espers than to him, he doesn’t show up and start investigating until a third of the way in.

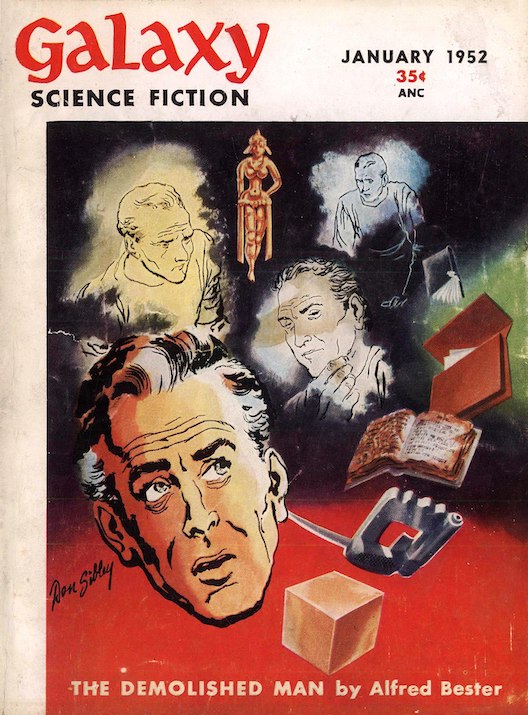

Reich’s the title character, after all, even if that title also telegraphs his failure. While book covers don’t come character-labelled, typically they seem to star Reich. Including the original cover of ’Galaxy Science Fiction’. We can assume that shifty foreground figure is him, with a suspicious Powell fixing his gaze on him.

GK Chesterton famously said: “The criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic.” And this book’s summed up by the idea of a critic-detective who’s also a psychoanalyst. It’s less about the discovery of physical clues, the mechanics of crime, and more about psychology.

For advanced, high-ranking Espers like Powell are able to achieve a kind of instant psychoanalysis, like the subconscious is just a subtext, footnotes accessible only to higher reading levels. To beat Reich, Powell will need to read him. So, added to all the other linguistic tricks, the book gets stuffed with ”broken images, half-symbols and partial references”, not to mention Freudian slips.

Which leads to another peculiarity. Psychology is not necessarily the same thing as characterisation, and Bester is clearly interested in one of these much more than the other. (Neither does it work allegorically, as some novels do, where the characters act as aspects of one head – one the id, another the superego and so on. Powell looks inside a head, he isn’t part of it.)

Nevertheless, insofar as there is characterisation it goes to Reich. Tellingly, when the book wasn’t open in front of me, I found I tended to forget Powell’s name. (Though it doesn’t help that Powell’s main character arc involves a young woman witness, whose trauma creepily manifests as ‘Daddy issues’ over him.)

And Reich prizes instinct (principally the killer instinct) and not just defies but opposes analysis. True, he has his own analyst. But he deliberately chooses a low-grade effort, who won’t be able to actually help him. So the novel becomes an attempt to psychoanalyse a character who does his best to refuse analysis.

”A Negative Infinity”

But what of the character who opens the novel, The Man With No Face, who literally haunts Reich’s dreams? Reich assumes this is his soon-to-be-eliminated rival, D’Courtney, and once he’s gone the dreams will go too. He continues operating on this belief, even after being told by an Esper it’s not so. Which becomes the mystery of the murder mystery, who is this figure?

Some canned Freud is opened: “Every man is a balance of two opposed drives - The Life Instinct and the Death Instinct. Both drives have identical purpose - to win Nirvana. The Life Instinct fights for Nirvana by smashing all opposition. The Death instinct attempts to win Nirvana by destroying itself. Usually both instincts fuse in the adapted individual. Under strain they defuse.”

Reich is an excess of the Life instinct, an embodiment of the egoistic belief that only you count, in fact it’s only you who is truly real, so it doesn’t really matter much how you treat others. “The essence of murder never changes,” he’s told. “In every era it remains the conflict of the killer against society with the victim as prize.”

This soon turns to full-on megalomania:

“He jabbed his chest with his thumb. ‘Want to look at God? Here I am. Go ahead and look… I don’t know much about this God business, but I know what I like. We’ll tear it all down, and we’ll build it all up to suit us.“

And there’s also the suggestion that this isn’t just psychosis speaking, that should Reich succeed he may become this powerful and change the nature of reality. Powell says to him: “Do you know how dangerous you are? Does a plague know its peril? Is death conscious?” (Though this isn’t really well developed or explained.)

And Powell’s response is to give Reich what he wants. Just too much of it. He creates a hallucination in which reality dissolves around Reich, first the stars, then the planets, closing in until he’s alone. As we’re told, “infinity equals zero”. Except he’s not quite alone, when all else goes he’s simply left confronted by the Man With No Face. A symbol of this absence that Reich’s crazed psyche always knew, at some level, it was pushing towards.

“Oh, Christ! Where is everybody? Where is everything? For the love of God!”

“And he was face to face with the Man With No Face who said: ‘There is no God. There is nothing.’

“And now there was no longer escape. There was only a negative infinity, and Reich and the Man With No Face.”

To create this hallucination, Powell must also become greater. But through a means that’s counter to Reich’s megalomania. In fact he risks his own life doing it. In Mass Cathexis all the Espers literally put their minds together, focusing their mental energy on one person. No-one (we’re told) has previously survived being the lens of so much power.

But then a twist on this. No Face is actually a hidden face, or rather “two faces blending into one.” D’Courtney, it transpires, was really Reich’s absentee father. Consciously he was unaware of this, but it drove his subconscious motive to kill him. His victim was not a thing, outside of himself, to be possessed or destroyed, but connected to him - even part of him. Hence he remains when the universe is gone.

Powell also says he’s Reich’s super-ego (or internalised ethics consultant), which often manifests as the Father, and so his sublimated wish for self-punishment.

A Malignant Flower

Yet I don’t think any of that was Bester’s real motivation to write this book. In fact, in a novel full of unconscious motives, I think that motive was unconscious.

Reich’s name suggests both ‘rich’ and ‘reign’, while his corporation, Monarch Enterprises, is somehow a tautology and oxymoron simultaneously. He describes himself as “ABC, audacious, brave and confident.” He’s bold, ruthless, goals-driven, sharp-witted, gruff and short-tempered yet charming when he chooses to turn it on, above all possessed of “the killer instinct”, at one point likened to a Neanderthal hunter. He’s an almost stereotypical capitalist, all that’s missing is the cigar for him to chomp on. And what makes him an effective capitalist is clearly what also makes him an effective killer.

In real life, if someone like Elon Musk committed a murder everyone would know it was him. In fact he’d be unable to stop himself bragging about it on Twitter. But then he’d get off anyway due to money and influence.

But in terms of fiction, this is natural enough. If in Shakespeare’s day bad Kings seemed an effective route to drama, we have bad capitalists. But the specifics differ, in crucial ways. See this seemingly incidental scene introduction…

“Despite all rival claims, pawnbroking is still the oldest profession. The business of lending money on portable security is the most ancient of human occupations. It extends from the depths of the past to the uttermost reaches of the future, as unchanging as the pawnbroker’s shop itself.”

Older than barter, Alfred? Care to tell us what’s on your mind?

It’s pretty well established that the roles given to women in this book are not what you’d call great. You’ve probably picked that up already, even though I haven’t been focusing on it. But it seems unlikely Bester was an active advocate for misogyny, the way (for example) Dave Sim is. More likely, he simply never thought about it and so recycled what was normative for his time.

And it seems similarly unlikely he was an advocate for capitalism, the way (for example) Ayn Rand was. Though active in the Fifties, his work seems uninterested in the perils of Soviet ‘communism’, often seen a staple of the era. As ever, his imagination stretches to visits to other planets, but is socially constrained.

Bester often tops and tails his work with a parable-like point. (You couldn’t really call it a moral, but it occupies the same formal space as a moral in Aesop.) The story in between can often feel like the mid-part of an essay, the working out. This novel’s no exception, and the opener is…

“In the endless universe there is nothing new, nothing different… There have been men without number suffering from the same megalomania; men who imagined themselves unique, irreplaceable, irreproducible, There will be more - more plus infinity. This is the story of such a time and such a man - The Demolished Man.”

But this time, does the point fit what follows? Many are the SF novels which propose a kind of New Feudalism. Were that the case here, Reich could simply have lost his divine right to rule. Instead, the existence of someone like Reich is seen as an inevitability. Capitalism, and Reich as its instance, is seen as a source of gravity, around which everything else must orbit. He can’t be just extinguished.

Powell tells him: “You’re two men, Reich. One of them’s fine; and the other’s rotten. If you were all killer it wouldn’t be so bad. But there’s half louse and half saint in you, and that makes it worse.” (And his murder weapon is described, equally dualistically, as ”a malignant flower.”)

At time Reich is seen in terms of megalomania, his grandiose folly leading to a fall. Then at others other of tyranny corroding kindliness, of a flawed character that can be redeemed. The novel steers to the first then veers over to the second.

And the ground has to be shifted for this to happen. From the title onwards, the threat of being ‘demolished’ hangs over Reich. It’s never explained, like a horror that can’t be stated. Until it actually happens, and we discover it’s some entirely new usage of the term which is actually something much closer to ‘cured’. Reich is psychically rebuilt, made into a model citizen.

Nothing we’ve seen suggests this world is a utopia. In fact it’s seemed a fairly regular dystopia, where the rich throw decadent parties and the poor stay poor, just without the murder. ”Strike riots” exist. (Which sound pretty good, but they’re probably not supposed to.) The very tone of the novel effectively bakes this in, with flip cynicism. (“It’s ten torn acres were to be maintained in perpetuity as a stinging denunciation of the insanity that produced the final war. But the final war, as usual, turned out to be the next-to-the final.”) Only for the gears to suddenly shift as we come across this attitude to the rehabilitation of criminals.

It also grates against all the Freudianisms that have populated the book up till now. Freud was scarcely a utopian, he more saw the human psyche as a battle perpetually fought between warring elements, with balance through stand-off the only thing to hope for.

In fact two things - one immediate, the other distant - are associated by fuzzy logic. We also discover that, in a reversion to the Tomorrow People trope, eventually everyone will become an Esper and it’ll all be fine. “The world will be a wonderful place when everyone’s a peeper and everyone’s adjusted,” explains Powell.

So why should this be? We’re told at one point Powell felt “anger at the relentless force of evolution that insisted on endowing man with increased powers without removing the vestigial vices that prevented him from using them.” (He’s thinking of telepathy, but it applies to capitalism just as well.)

Then later, we’re told just why Reich has to be rehabilitated.

“If a man’s got the talent and guts to buck society, he’s obviously above average. You want to hold on to him. You straighten him out and turn him into a plus value. Why throw him away? Do that enough, and all you’ve got left are the sheep.”

Turns out it wasn’t really humanitarianism, he’s needed because he’s so special. So the circle is squared, we can have our capitalist cake and eat it. We need the ruthless, predatory bosses, you know, the do-ers. But how do we corral them, stop them going too far, get them with the ruthless streak that’s just the right width? How do we allow the wolves to keep moving among the sheep?

The answer is pushed into the future. Even the future of a future-set SF novel in which people can mind-read and visit other planets. Bester is trying to fix the system he lives under, rid capitalism of its contradictions. But to do this, he has to project it into tomorrow. Then can’t make it hold there either, so projects further, into the future’s future. But it’s incoming, here one day, honest. Keep the faith, citizen.

Coming soon! To guess our next destination, look up…

Turns out it wasn’t really humanitarianism, he’s needed because he’s so special. So the circle is squared, we can have our capitalist cake and eat it. We need the ruthless, predatory bosses, you know, the do-ers. But how do we corral them, stop them going too far, get them with the ruthless streak that’s just the right width? How do we allow the wolves to keep moving among the sheep?

The answer is pushed into the future. Even the future of a future-set SF novel in which people can mind-read and visit other planets. Bester is trying to fix the system he lives under, rid capitalism of its contradictions. But to do this, he has to project it into tomorrow. Then can’t make it hold there either, so projects further, into the future’s future. But it’s incoming, here one day, honest. Keep the faith, citizen.

Coming soon! To guess our next destination, look up…

No comments:

Post a Comment