“My art is evidence of my freedom”

- Thornton Dial

Birds Unflown

This show is subheaded ’Black Artists From The American South’, raising something interesting right at the start. The Great Migration, a pivotal event in Black American history, saw unprecedented numbers escape Southern segregation for newly opened-up jobs in the Northern cities. As this led to developments such as the electrification of Blues, we tend to think that when they left they took culture with them. We even came to use ‘urban’ as a polite euphemism when we didn’t want to say ‘black’.

The Civil Rights movement, starting in the mid-Fifties, may have been based in the South. But as that turned into Black Liberation, both broader in scope and more radical in expression, it expanded North and West, and took up more of a cultural form. The Tate’s recent show ‘Soul of A Nation (Art In The Age of Black Power)’ largely focused on this.So those who got left behind in that migration, surely they just got left behind. There were, in words from a work here, ’The Birds That Didn’t Learn How To Fly’.

Like all such assumptions, as soon as you say it out loud you see the absurdity of it. The majority stayed in the South, after all. So this show arrives as a welcome correction.

Both title and exhibits come from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Community Partnership of Atlanta, “dedicated to promoting the work of Black artists from the American South and supporting their communities by fostering economic empowerment, racial and social justice, and educational advancement”. And the title comes via a poem by Langston Hughes.

Most of this art was created not just outside of the art market but without access to art materials, and so was made with whatever the artist managed to forage. Take for example Lonnie Holley’s ’Copying The Rock’ (1995), below.

Holley himself has given us a choice of two explanations. The guidebook quotes him: “We can’t just copy the past. We got to deal with the new. Sometimes it’s like living in hell.” While Laura Porter writes of attending a talk where he said it was about the unreproducible quality of nature, where a photocopy of a rock is at best a poor approximation of its source. Which makes it sound almost like Magritte – “Ceci n’est pas un rocher”.

And who would be vain and rash enough to disagree with an artist about his own work? You’re looking at him. For more, I would say is afoot. Neither accounts for the seismic violence in it, as if the copier had been destroyed in the attempt of copying. Then there’s that savage statement scrawled on the lid - “it’s like I’m living in Hell”. (Alluded to only in the first explanation.)

It suggests to me the black American experience is a kind of unparseable truth, an oppression so extreme and so ingrained it can’t be communicated - any attempt will just wreck the recording device. I doubt you’re supposed to think of it, but it brought to my mind the famous Malcolm X quip - “we didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on us.”

Art is so often views, windows onto other places. Which we then rate according to how realised those other places are. Whereas Ronald Lockett’s ’Oklahoma’ (1995, above) is precisely the reverse, a frame without a picture, a kind of anti-window, the grille added almost as a taunt. It’s not a portal but a blocking device. And a most beleaguered one at that, various strips of sheet metal stuck together as if repeatedly patched up against the pitiless elements. The accumulation of sedimentary layers comes to be a common motif here.

Why’s it called ’Oklahoma’? Especially when the artist was from Alabama. That 1995 date is a clue. It commemorates the Oklahoma City bombing, where white nationalist terrorists killed 168 people.

And this sets the tone. References to oppression as a physical force run through the show, but the expression is normally oblique. There’s some drawings by Thornton Dial, with titles like ’Katrina’ (2005) and ’Slavery’ (2009), but the images aren’t the direct expressions they would suggest. Their dominant theme is discombobulation. ’Slavery’ may well be set in a plantation field, but it's a whirl of body parts as if they’re being washed down some giant plughole.

While his ’Blue Skies: The Birds That Didn’t Learn How To Fly’ (2008, above) hangs rags weatherbeaten from a line. They’re hung so low the image is dominated by that sky, which is actually gun-metal grey. It looks more like another oppressive weight than an escape route. And dour, acerbic titles such as that recur. Joe Minster titled a sculpture ’And He Hung His Head And Died’ (1999, while Richard Dial (Thornton’s son) called a 1988 piece ’Which Prayer Ended Slavery’.

Art As Alchemy

But everything above, while true, makes it too easy to overlook an equally vital fact - this art is not just creative and inventive, it’s actively playful. It’s like the famous story of the young Miles Davis being told by a college lecturer that Blues was the raw, inarticulate cry of the suffering black man, and him shouting back “you’re a goddamn liar!” The Thornton Dial quote up top… it’s up top because, if there was one takeaway you should take from this show, it would be that.

And this sense can’t be separated from the use of found materials. Ralph Griffin’s ’Midnight’ (1978, above) is really not much more than a bit of old wood. We effectively accept that art can find nascent identity in organic things. Sculptors commonly say they already see the shape inherently in the block of material, which their work only realises. So it’s only a small step to noting that you position a piece of wood in a certain way and it already resembles something. But just as significant is what he adds, the tin legs, the red plastic for eyes. To find life in nature, even dead nature, is one thing. To do it for tin and plastic is another. In a splendid detail, the nails that hammer in those bits of plastic become the pupils for the eyes.

Hawkin’s Bolden’s ’Untitled’ (1989, above) is more an assemblage than Griffin. The source of his materials, an old pot, a section of drainpipe, a baking tray, could scarcely be more obvious. So obvious there’s something comical to it. But there’s something charged about it too. It’s simultaneously a bunch of stuff stuck together and an entity.

Thornton Dial’s ’Tree Of Life (In the Image of Old Things’) (1994, above) decorates a wood assemblage with paint and decorative objects, including a crown. The concept of a single tree as the wellspring of all life is well known across cultures. Here Dial applies it to dead wood. Creativity can bring fruit even to barren trees.

The bird figure, in monochrome green, doesn’t seem an obvious addition. It cannot be resolved into a scene, it isn’t standing before a star field, its stepping out of the work and its dead eyes meet our gaze. (The guide suggests he’s an alter ego for the artists, like Ernst’s Loplop.)

What kind of mind looks at an old tin can and thinks of stars? My brain boggles at even the prospect of it! Dial described art as “a bright star up ahead in the darkness of the world.” And the quote which came unprompted to my mind this time was Wilde’s, “we’re all of us in the gutter, some of us looking at the stars.”

The show says “theirs is a story of transcendence, of the recuperative power of recycled - and reimagined - material.” And there is something alchemically transformative in turning detritus into stars. The origins of materials are normally hidden in art, mere props for the artist to exert their will upon them, their previous state pushed into the background. Think for example what a statement it is for a painter to leave even a small area of bare canvas on a work. While these materials are taken up less with a sense of “I will defy these constaints by finding a way to work with what you have reduced me to.” And more “hey, more cool stuff in this other dumpster over here!”

These old bits of driftwood or junk are transformed but also somewhere between elevated and realised, as if they had buried qualities only now brought to light. Some of the artists have commented that they themselves felt written off, allowing them to identify with the discarded. “I had been thrown away as a child, and here I was building something out of unwanted things,” said Lonnie Holley. Perhaps we should see the materials more as collaborators.

But while found materials might work for sculptors and assemblage-creators, it’ll be different for painters, right? Wrong. Mary T Smith’s ’Untitled’ (1984, above) doesn’t just use distressed piece of old corrugated tin for a canvas. It utilises those corrugations to capture the coloured stripes in the design. It’s not like she needed something to work on and in desperation resorted to this, it’s like the material inspired the composition.

Jimmy Lee Sidduth painted on board rather than canvas. For which there is a tradition. (Well, more of one than there is tin.) But he painted with with grass stains, berry juice or - in ’Atlanta’ (1988, above) - mud. The restricted palette and painted borders are primitive. But the road leading up to the cityscape, with its ever-escalating towers, soaring till they touch the upper border? That isn’t so different to the way Nevinson depicted New York. Part of the appeal is the dynamic fusion of ‘folk’ forms with ‘modern’ content, a folk-art city.

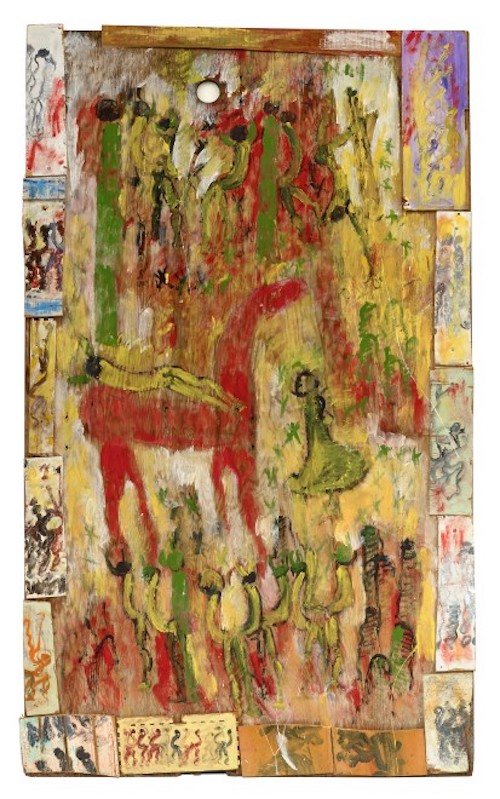

While Purvis Young’s ’Carrying the Angel to the People’ (1994, above), is a kind of synthesis of stained glass windows and cave art. Particularly conveying the latter is the use of red ochre, a commonly available ‘paint’ even in stone age days, and the dominance of that giraffe-like animal. (Young apparently calls it a ‘freedom horse’.) While the sense of several scenes inside an overall design is more stained-glass window. We may note that, however varying those forms are in our common response to them, both are forms of religious art, and Young often gives his work religious themes, his figures sporting halos.

Not All Art is Protest

But we should also look at the exceptions here. Not all art is protest, not even by the extended definition we’ve come to here. And we should protest the notion it should be. Nor are black artists obliged to make ‘black art’. Charlie Lucas’ scrapyard assemblage ’Three-Way Bicycle’ (c. 1985) is Dada, resembling a functional object less and less the more you look at it. While the figure looks less riding the bicycle than part of it.

While Eldren M. Bailey’s plaster sculpture ’Dancers’ (1960s, above) captures the sweeping contours of those figures, even to the point of bending anatomy, in a way similar to Matisse. Their hair could be said to be in black style, but the theme of the work is simple love of the dance.

Primitive Modernists

So, does all this mean we’re looking an an exhibition of outsider art? Formally speaking, these folk operated outside the art market, or at least for much of their careers. And if this was all that was meant by that term, it would be fine to use. But the point is… it’s not, is it? And in fact its nebulousness is a large part of the problem.

We often like to romantically imagine pure outsider artists, possessing what we lack, uncontaminated by the art world the way noble savages are by civilisation. But while this art may have been made by marginalised Americans, they were still Americans, not some lost tribe in pure isolation. There’s every indication they were aware of developments in art. Dial’s ’Blue Skies’ looks like someone who has seen Abstract Expressionism, for example.

Nor was the influence just one-way. It’s impossible to see this show and not think of Rauschenberg. But it seems that, Texas-born, it was Rauschenberg who saw and became influenced by this art rather than the other way around. He was of course a great artist. But it’s another case of white folk gaining recognition for picking up on what black creators were doing. It’s like being told by everyone Captain Beefheart was a true original, then discovering Howlin’ Wolf.

A more interesting question might be, how aware were they of primitive art? Joe Minter devoted a whole area in Alabama to his works, which he called ’African Village In America’. And he’s quoted as saying “I’m listening to the ancestors coming through me to you”. Yet there’s no particular reason for a Black American to find their identity in that, any more than I look on the Sutton Hoo hoard and see myself. It’s the black American experience we see expressed here.

But at the same time… even if you’ve no greater empathy with primitive art, with its totemic functions, you’re less primed to treat it reverentially. You have more a sense of “this is mine to play with”, it becomes more malleable in your hands. What Minter thought wasn’t true. But believing it was empowering nonetheless.

And this cannot help but lead onto another question…

Unsurprisingly, artists without access to art materials didn’t tend to have much access to art galleries either. So came the yard show. One Americanism we Brits have had to grapple with is the yard sale. To sell off our tat, we need to lug it to a flea market. While they just turn their front yard into a shop. Now it seems we need to add to this the “distinctly Southern phenomenon” of the yard show, art taking the place of tat.

It’s not specified, but despite the common name it doesn’t look like this was a way to sell work. (And your neighbours were unlikely to be any better off than you.) It seems more about having a space to build up your works, until they combine into a kind of installation piece. The guidebook has a photo of Good Bread Alley in Miami which Purvis Young has pretty much entirely covered in paintings, even at the price of them overlapping one another (below).

And this takes us to yet another question - how was all this viewed by their neighbours? Was it seen as creating an indigenous black culture, or articulating popular concerns? Did artists become local celebrities, perhaps not always understood but still championed for brightening up their neighbourhoods? Were they tolerated as eccentrics, like Alfred Wallis in St. Ives? Or dismissed as weirdos? The show doesn’t consider this at all, alas.

Which leads to the most common criticism of this show, that it treats the work too reverentially. If its habitat is the accumulated yard sale, this art exhibition looks more like an art exhibition. (See for example the Time Out review.) I’m semi-sympathetic to this, but wonder if the yard show works best for individual artists or self-defined groups, so it doesn’t really matter if everything sloshes together into one mega-work. While round robin shows such as this may require some separation between the pieces. (There should be more photos and videos of the yard shows, that much is true.)

The works here date from the Sixties up to today. (The most recent being from last year.) Which means it starts at pretty much the point Modernism expired. Visit most contemporary exhibitions and they just look moribund, a corpse stuffed with some po-mo buzzwords. And you come away sadly concluding that ours is just not the era for visual art. Except here the art is not dry and sterile at all, but bold and alive. It virtually crackles with creativity! It’s like the primal purpose of art has not been forgotten after all. And yet we only hear of it now?

The question is of course its own answer. Ultimately, it’s not our times that screw up visual art, so much as the dead hand of the art market. Like the tourist industry does to places, it seizes excitedly on anything outside itself but only to subsume it. Outside that ever-grasping shadow, artists can still create.

Which raises the question, is there an way we can discover art like this, without it falling under the Art establishment’s sway? In short, there isn’t. There’s no showing this stuff in a secret hush-hush gallery, and not telling Jonathan Jones. Further, it’s true to say that all the disadvantages these artists faced became their advantages. But it’s also easy to say, for us at least. Subsisting is not always the easiest way to live, and finding a market to sell your wares had obvious advantages. The art market is a form of the labour market, something we may not like but can’t simply ignore. While we continue to live under the system we live under, there’ll be no right answer to this. But this show’s a testament to the credo that creativity will always find a way.

No comments:

Post a Comment