“I like to channel naturalist, abstract, ornamental, fetishist and childish images”

- Paula Rego

Fighting Fascist Realism

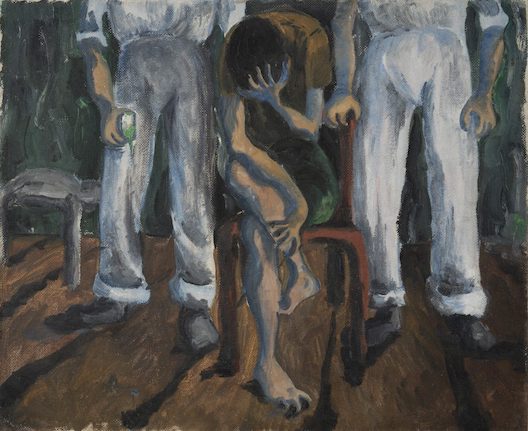

Paula Rego was born in 1935, in a Portugal still under fascism. Remarkably, she painted ’Interrogation’ (1950, below) while just fifteen. The - for want of a better word - purity of those interrogator bodies is emphasised by the echoing whiteness of their symmetry, and by their headlessness throwing emphasis onto their puffed-up torsos. Which contrasts with the poor figure in the chair, so twisted and contorted. It’s a remarkably assured work for someone so young. But if you were to pin it to a label you’d pick Expressionism.

Whereas ’Salazar Vomiting the Homeland’ (1960, below) is more indicative of her future direction. Its wild reductions and distortions of the human figure, its colours so vivid it almost looks like the work vomited itself into being, these are more reminiscent of Surrealism - particularly Miro. And, not unlike Miro, at the same time it keeps up the political themes. Salazar was Portugal’s dictator.

Surrealism, we should remember, emerged in opposition to fascism - aesthetically as much as politically. Propaganda art typically aims to appeal by making easy sense out of complex subjects. So, against its neat and tidy imagery of heroic male figures rendered in almost geometric anatomy, Surrealism twisted and stretched the human body until it was barely recognisable. And fascism, let’s remember, was perfectly able to recognise this in its enemy.

By 1951 Rego had been moved by her liberal-minded parents to England, the following year enrolling at the Slade. So it’s entirely possible that, with home censorship, the Portuguese artist only saw the work of the Spanish after arriving here. And there’s no denying her most impressionable years were spent under Salazar’s controlling maw.

Nevertheless, the show perhaps makes too much of these early years. It talks about the restrictive roles fascism forced women into, accurately and understandably. But it seems needlessly narrowing to confine her art into a response to this. If patriarchy was your prison, a move to Fifties England was a sure-fire way to discover its bars didn’t end at Portugal’s borders. In fact in ’57 she moved back there to have a baby out of marriage, after undergoing several abortions. And if we’re to take abortion as a barometer of women’s freedom it wasn’t legalised in England until 1968, then Portugal in 2007. Some while after Salazar had ceased vomiting.

Besides, that was scarcely the limits of it. One exhibition refused to display ’Salazar’, not in fascist Portugal but supposedly liberal London.

Added to which, if fascism held sway in her homeland until the shockingly late date of 1974, Rego was there to witness its end. The later work ’Madame Lupscu Has Her Fortune Told’ (2004, above) features the widow of the would-be dictator of Romania, who’d fled there. She’s pictured beside a seig-heiling statuette while attempting to get a blank palm read, fascism reduced to no more than a sick form of nostalgia for atrocity. (Oh to be back in the days when it seemed something consigned to the past!)

More widely, it risks mislabelling her art at agitprop. If ’Interrogation’ could have illustrated an Amnesty leaflet, ’Salazar Vomiting The Homeland’ requires you to read the title to get the context. And this is the vein in which she continues. In the accompanying filmshow she comments art should be as much about what’s inside you as what’s outside.

We see this in her collage works, which ran through the Sixties and much of the Seventies. (Though the term’s a little misleading here, as she chiefly collaged her own drawings.) ’The Firemen of Alijo’ (1966, above) was based on a sight she witnessed, the Portuguese poor barefoot in the show and huddled around a fire. But the finished work is so far from this that it’s more impetus than basis. In Rego’s hands, the scene becomes a phantasmagoria.

That green stripe is a horizon line, or perhaps the base of a wall. And the left-most figures do stand barefoot upon it. But from there they’re arranged in a grand sweep across the canvas, which trails out just before reconnecting to the ground. And the colour scheme becomes bolder and more varied as that sweep progresses. The result is such an accumulation it becomes an assault on the senses, which takes some while to resolve. Other works follow this arrangement, such as ’Manifesto for A Lost Cause’ (1966).

The ground-as-base is reminiscent of children’s art. But it also seems employed as a thin thread to perspective, and with it the naturalistic conventions of art. It’s there largely to show what is being left behind, try to stand on that seeming solid base and you’ll soon be yanked off our feet.

Painting With Children + Animals

In 1974, for the first time, Rego illustrated some Portuguese folk tales. And there were not just more works to come in this vein, the themes would creep into her art more generally. (Yes this was the year the dictatorship fell, for those who like to make something of such things.) Perhaps the main thing is how little she has to change them to make them hers. It’s like she isn’t twisting or making use of them, they really were this sinister all along, just without us noticing. Take for example the print of ’Baa Baa Black Sheep’ (1989), below.

Slightly earlier, but in what seems a related move, she began making what she called ‘dollies’ - soft-form creations, something like home-made children’s toys. Though the show calls them ‘sculptures’, and though no article on her is complete without a photo of her studio festooned with them (see Wikipedia for an example) unlike Dorothea Tanning she doesn’t seem to have seen then as art objects in themselves, but as props to incorporate into her artwork. They were something like a Commedia Dell’arte troupe she could have on standby. From this point on her art is regularly rooted in the ‘types’ of folk tales, fables and fairy stories.

In the early Eighties she began a series of bold, thick-lined acrylic works, often on paper, largely featuring animals. Take for example ’Red Monkey Offers Bear a Poisoned Dove’ (1981, above). It looks so stark and bold, with everything handily labelled by that descriptive title, it must surely have a straightforward meaning. A poisoned dove is admittedly an easy enough image to read. But why a monkey, why a bear? We realise we’ve been looking at it for a while, waiting for this straightforward meaning to emerge, then a little later that it won’t.

A bunch of responses suggest themselves (countries in the Cold War?, characters in Rego’s life?, psychological archetypes?), yet none stick. And in this way it reflects the simple, direct prose which fables and folk tales are told in. In a Guardian interview she confirmed: “I always need a story. Without a story, I can’t get going.” But the story is often like the witnessed scene in the earlier collages, not something to illustrate but break off from.

Other works in this era are large-scale, and built up from the baseline like the earlier collages. However now they’re more mural than collage, a series of smaller pictures with linking devices. Some you even read by following a series of ‘lines’ across, like a piece of text. ’The Raft’ (1985, above) is the only one to be arranged around a central motif. And, while that blue dragon seems to personify the sea, the girl on a raft seems more adrift amid a sea of images. And she sits dispassionately through it all, a solid central block amid the pandemonium.

And this Girl character recurs frequently, as in ’Girl And Dog’ (1986) where she shown absurdly shaving the dog’s throat. There’s a biographical reading here, this was the year in which her husband Victor got Multiple Sclerosis and she inevitably became his carer. (Something we’ll see in other works.) But more important may be that impassive expression.

The show takes her as a feminist heroine. Perhaps partly, but she never seems wild and free. More accurately, as Laura Cummings pointed out in the Guardian: “The dogs have a whole range of expressions, but the girl… has only one. She is a vision of fixed determination.” She seems what we aren’t, calmly accepting of this absurd world. We should remember a child doesn’t have the same relationship to animals as an adult. And this Girl is shown either living in a world of animals, or morphing into one herself.

She comes closest to an expression with ’The Little Murderess’ (1987, above) where a trace of a smirk crosses her face. The standard reading seems to be that this is again about her Victor, perhaps the return of the repressed part of her psyche that could do without the constraints of caring for him. The Pelican, we’re told, can be a symbol of self-sacrifice.

But could it not also be a metaphor for growing up, the adult ‘murdering’ the child by replacing her? Look at the way she’s virtually emerging out of the picture frame, leaving her old world behind. The objects behind her, the toy cart and brightly coloured chair, look like something from a child’s room, a room she’s leaving. And we see a spectrum as if it’s a timeline. The most vivid red is in the chair to the very right, the most vivid green in the stretched-out ribbon to the left.

Into Tableaus

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, because in the late Eighties Rego pulls another switch. She embarks upon large-scape acrylics, which are set in recognisable pictorial space. Colours, once almost impossibly vivid, become more muted. And while animals still appear, in this era there’s less of the human-animal hybrids.

Yet at the same time as perspective opens there’s neither movement to the work nor naturalism to the figures. They’re beyond realist, in their smoothness they’re idealised, almost hyper-real, paintings with the sharpness of line drawings. They’re tableaus, as arranged as in any diorama, their poses and gestures feel weighted with meaning. Even when we’ve no real notion what that meaning might be. They can be like looking at a nativity scene with no knowledge of the Bible.

Take for example ’The Policeman’s Daughter’ (1987, above). There’s no reason why you couldn’t re-enact the scene in real life. But that pure white dress, for example, is too pristine to exist in the real world, let alone for the messy task of boot polishing.

The title gives away whose boot is being so dutifully shone, recalling the ever on-stage synechdocheal boot in Strindberg’s play 'Miss Julie’. And the arch-backed black cat, who we can safely assume is a Tom, effectively rhymes with the boot.

Just as the wilder, free-form style went with agitational content, so this aesthetic plugs into a politics. But quite a different politics. It’s an illustration of patriarchy more than an assault on it. It seems simply too ordered to allow for change. The style dictates the tone - “this is just how it is”. And perhaps the world feels more like that as we grow older, the things we once assumed we could mould have instead moulded us.

And it should also be said that folk tales and fables, inherently common property, are inherently subversive - but they’re also fatalistic. They’re not concerned with politics, with events in the world, but with the essential state of things. Their animal figures suggest we are simply born to live out our nature.

Except, as you may have guessed, things aren’t quite as neat as they look. In ’The Family’ (1988, above) a male figure is attended by two females - this time dressing him. But he’s both obscured by and sandwiched between the two. And as they exchange a glance a third looks on with clasped hands raised, like the criminal mastermind of the enterprise.

Unsurprisingly this is another Victor picture, illustrating the way care work determines an intimacy that’s inherently not between equals. But like the Portuguese poor this is more impetus for than meaning of the work. It’s based in the ironic relationship of the servant to the master, as they make him up they simultaneously wipe him out. Look to the diorama on the chest of drawers.

And ’The Maids’ (1988, above) follows along the same lines, based on a Genet play about servants who murder their mistresses. A Maid isn’t just the central figure, her extended limbs dominate the frame, shadows splaying out from her, while her Mistress is closed up on herself. There’s still a kind of fatalism here. But it’s a fatalism in reverse to the existing order, in which the servant will inevitably rise and the master fall.

There’s also… um.. a wild boar in the room. In fact a motif of Rego’s in this period is to incorporate such an element, nromally in the lower right foreground. In the two examples above, these are entirely explicable. But it’s as often jarringly incongruous, out of scale or - as here - something of both. Earlier, her base lines kept her work semi-anchored in realism. Now it’s the reverse, she stays linked to her Surrealist roots.

To quote Laura Cummings again: “The Tate wants to make an activist of Rego… But the artist is ill-served by this reductive brief. Her gift is for the exact opposite: for the deeply ambiguous and morally disturbing scenario.”

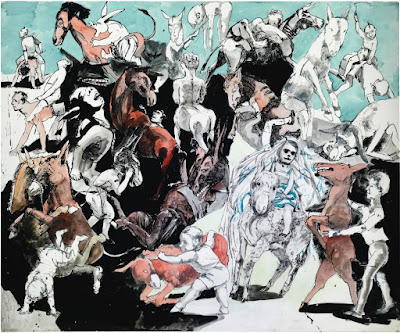

The ink-and-watercolour work ’Island of The Light’ (1996) is part of a general return both to mural style and fable-based content. It’s based on a scene from ’Pinocchio’ where children are stolen and forced into labour, causing their transformation into donkeys. (Nicely, Rego was inspired by watching the Disney film while a child herself, rather than researching folk tales at the British Library or some such. It suggests both a personal connection to the material, and that something in these tales survives even Disneyfication.)

Rego slips between every variant of this motif: two-legged donkeys, humans riding donkeys, humans riding humans, humans with donkey heads, even a donkey mounting and biting a horse. It suggests something compelling but irresolvable about the central image.

It’s a classic child fantasy, to transform into an animal in order to roam free, unbridled by the social conventions adults try to impose on you. But the concept is double-edged, for at the same time the child’s aware that animals themselves can be made beats of burden. So what should be a means of escape here becomes a form of capture. And the jumbled nature of the composition suggests no way out.

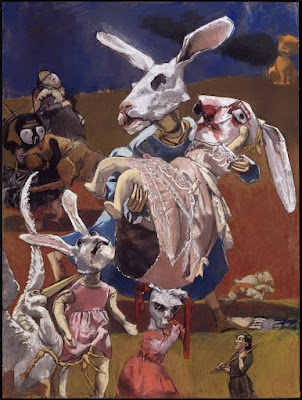

’War’ (2003, above) is again based on something Rego witnessed, though this time at one remove. It’s based on a newspaper photo of the invasion of Iraq, which featured a screaming girl in a white dress. It’s a starker image than 'Island of the Light’, but still elusive when you try to pin it down. It’s partly inverting the folksy kid-lit image of cutesy anthropomorphised figures, with the bloodied rabbit masks. But there’s more…

There are almost as many variations as ’Island of the Light', just within two figures. The main figure has a rabbit mask, but human hands and feet, while the child she carries sports paws. The adult’s ‘mask’, dead-eyed, could equally be an enlarged rabbit skull. (And the death figure with animal skull appears elsewhere in Rego’s work, for example ‘Scarecrow and the Pig', 2005.) Yet the child’s looks bent from shape, as if papier-mache. You can’t see this as actual rabbits. But neither as people figleafed by anthropomorphism, or actors in rabbit masks. You need some combination of all of them at once.

With all the twists and turns, ’The Raft’ may well be the central image, itself depicting being at sea amid a flood of images. Rego is simultaneously compelling and inscrutable. But perhaps best of all, this is not just a retrospective of a living and working artist but one whose more recent works are still well worth seeing. And, while the content of Rego’s art may often seem less than uplifting, that seems a reason for optimism…

"There’s no denying her most impressionable years were spent under Salazar’s controlling maw."

ReplyDelete"Maw" means mouth. Is that really what you intended here?

She painted 'Salazar Vomiting the Homeland', I was riffing off that.

DeleteI'll accept it.

DeleteIn other news: "art should be as much about what’s inside you as what’s outside".

How do we feel about sentences that begin "art should"? :-)