The

latest in a series on artists who dealt in abstraction and

semi-abstraction. (Which is of course a thin cover for this being

another art exhibition review which gets written up absurdly late.)

Previous entry, on Kandinsky here.

“By

Suprematism I mean the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To

the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in

themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling.”

- Malevich

The

Modernist Magpie

For

the longest time, I associated the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich

with Mondrian. An artist whose formulatory early years turned out to

be their best work. An artist who, as soon as he'd figured out what

he wanted to do, had boxed himself into a corner. In Mondrian's case

a yellow box, in Malevich's a black one. But the same difference. His

Black Square, beloved of art history books, was a full stop – the

cul de sac of the path of abstraction. Once it was reached there was

nothing left to do but turn back again.

With

Mondrian, I still contend that's pretty much true. Yet Malevich's

story turns out to be richer...

For

an artist renowned for having so singular a style, it's weird to

watch Malevich starting out by looking like everybody else. And it

really is everybody else. He's able to cycle

through so many Modernist styles so quickly, taking from each

elements that suit him, like a Magpie in flight. Just get ahead of

yourself for a second and scroll down to glance at at the next six or

seven illos. They're not just from the same hand, they were created

within a four year period.

Seeing

an exhibition like this can be like reading a book where you already

know the ending. It can distort your vision of what's happening right

now. So, despite our natural tendency to look for Malevich expunging

elements from his art, we should pause a moment to consider what

stays. Abstraction is commonly assumed to lead from landscapes or

still lives; the human figure so strong an image in our minds it

needs to be suppressed before we can start to see a picture's formal

elements. (Try looking at a still life of a vase of flowers merely as

shapes and colours, then try the exercise again for a portrait.) But

the human figure remains dominant, perhaps even a fixation, in

Malevich's art right up to the switch-over. A rare landscape can even

be called simply 'Landscape' (1906).

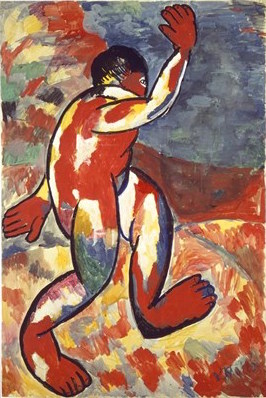

Matisse

is a visible early influence, for example in 'Bather'

(1911, below). With it's bold outlines, it's real or apparent blocks

of vibrant colour, it's an evocation of movement. It's audaciously

simplified figure shows little interest in anatomical accuracy, the

torso is simply a sausage from which protrudes oversized flapping

hands and striding feet.

Malevich

soon joined the Donkey's Tail group. With a name presumably working

as a self-styled irony, they determined not to be merely imitative of

art abroad but (as the show puts it) “fusing the innovations of the

Western avant-garde with the simplified forms and expressive colour

of [their own Russian] popular prints and religious icons.” And as we saw with the 'From Russia' show, this would prove a

potent cocktail. The magic beans of Western Modernism were brought

back and plant in the rich soil of Russian folk art, leading to some

very bold beanstalks indeed.

The

common folk became the subject for painting, with an almost totemic

emphasis on the figure of the Peasant. He's clearly seen as the

emblem for Russia, much as John Bull was for Britain. But paintings are frequently

named after their central figures, who are themselves named after

their activity, such as 'The Floor Polishers'

(1911/12). Their facial features are normally boldly outlined,

evoking types rather than depicting individuals. See for example

'On the Boulevard' (1910, below), where the figure

is emphasised by being thrust out at you. If we include the bench he

sits on, he extends beyond the frame in all four directions, with a

disconnected landscape placed behind him like a theatre flat.

But

Malevich was already moving beyond Matisse. In for example ,'The

Scyther' (1911/12, below) the background is reduced to

shades of red, and works somewhere between a scene and a form of

patterning. It offers a vivid colour contrast to the foreground

figure. With his neatly gradated black and silver-grey (looking

almost like a piece of modern vector art) and mask-like face, the

figure looks as metallic as the scythe he carries. And yet, rather

jarringly, his feet are unshod.

And

this change was coming through fresh winds blowing from the West. The Knave of Diamonds exhibition of December 1910 first brought

Cubism to Russia, and spawned an indigenous group named after it.

However, as we saw in an earlier review, distance allowed the Russians

to take the seemingly irreconcilable Cubism and Futurism and combine

them into their own synthesis – which they promptly (if

uninventively) titled Cubo-Futurism. Nevertheless, most examples were

more Futurist, more concerned with dynamism and speed. (See for

example Natalya Goncharova’s ‘The Cyclist’, 1913). Malevich,

conversely, stayed closer to the more contemplative Cubism.

With

'Head of a Peasant Girl' (1912, above) Malevich

employs sombre browns and greens, the cooler colour scheme of Cubism,

rather than the bright blocks he'd first borrowed from Matisse and

were still being employed by the Futurists. The show finds “the

title challenging the viewer to find the trace of a recognisable

image in a complex arrangement of planes”. You can't, and yet like

a Zen exercise the image seems perpetually just out of reach.

The

title actually has a second challenge, for there's a pleasing irony

in Malevich insisting so modern a painting should still be dedicated

to a Peasant Girl. Yet at another point he seems less assured that he

can continue to combine his influences. 'The Woodcutter', effectively a sequel to 'The

Scyther', has on it's back 'Peasant Women in Church' (both 1912), not only a more traditional piece of folk art but, as

its title would suggest, religious in theme. It suggests an artist

divided, not sure which way to go.

And

yet he did. Modernism is often caricatured as a series of dry, formal

innovations, hermetically disconnected to anything outside the artist

world and its fixations. And if there's a moment of truth to that,

Cubism is it. It's innovations weren't important so much as

revelatory. But it was art for artists. And those artists needed to

swallow it down, learn it's lessons and move on. That's pretty much

what Picasso did, and he was the school's co-founder. And that's

precisely what Malevich does. His Matisses, however good they look,

are merely more Matisses. Whereas his Cubist works, however typical

they look, show him already working his way out of them.

As

if the brew wasn't already heady, Dadaism is then thrown into the

mix. Though it was never named as such in Russia it seems to have had

the same impetus as in Germany, the looming shadow of the First World

War. In 1913 Malevich collaborated on the 'Zaum'

manifesto which boldly called for “the dissolution of language and

the rejection of rational thought”, and started wearing the

signifying wooden spoon in his buttonhole. The signature paradox of

Dada, nihilist destructiveness combined with wanton playfulness, is

at work - though in Malevich's case... well, let's check out which

face is uppermost.

‘American

in Moscow’ (1914, above) is a reason-defying collage of

objects, including that identifying wooden spoon and the (at least in

the popular mind) arch-Surrealist totem the fish. Among the

chopped-up words and images are three chopping devices – a sabre, a

saw and scissors. Even the scales on the fish's back, emphasised by

being placed before the man's face, look sharp enough to cut.

Writing in the Telegraph, Richard Durrant comments “accomplished

as all these early pictures are, every single one is a pastiche”.

He’s right. But they’re so accomplished. And

both those points are nowhere more true than with this work. It's

almost the consummate early Malevich.

Beneath the chaotic jumble it's well-composed... in fact too

well-composed, too realized. Dada relishes in its nihilism,

audaciously defying you to find it aesthetic. It's disruptive,

volatile and even violent. Whereas this is art merely masquerading as

anti-art. It's a great work of art. That's its success and its

failure.

Nevertheless,

it was Dada rather than Cubism that was to prod Malevich into

abstraction. And that's less surprising than it might appear. Though

people commonly couldn't find the images in it, Cubism was never

intended as abstract or even proto-abstract. It treated objects much

like flat-pack furniture in reverse, it took the seeming solid and

disassembled it. It asked why we'd want to see objects from just one

perspective in art, when that's not the way the world works. But

multiple perspectives would prove not liberating enough for Malevich.

Not

that Dada was any more proto-abstract. It sought to undermine

language's functionality at the point of use, to make its descriptive

powers seem arbitrary and thereby meaningless. But the lesson

Malevich took from it was ultimately different - that you could cut

language from its earthly moorings, and rather than use it to point

at objects attempt to express the ineffable. “Zaum” was most

likely a nonsense term akin to Dada itself, a jeer at language's

inadequacy. The nearest English equivalent might be “blah”. But

Malevich seems to have taken it to mean something more like “aum”.

Coined to express nothing, he took it to mean everything.

And

so he went and painted a big black square.

Be

Square

'Black

Square' (1915, above), as he decided to call it, is called

by the show “one of the iconic paintings of the Twentieth Century”

or

by the Times' Rachel Campbell-Johnston the “Mona Lisa of

Modernism”. (She uses the line early, so it pokes above the parapet

of the great Murdoch paywall.)

The

date I've given above follows convention, it's when the work was

finished. But Malevich himself always used 1913, when he first had

the idea. Which suggests it might even be the the first conceptual

work of art, its idea more important than its realisation. (The same

year, in 'Village' he simply wrote the word

“village” on a canvas, arguing that “encompass[ed] the entire

village” rather than get tied down in specifics the way an image

inevitably would.)

And

look when it comes. It wasn't the full stop I'd previously imagined.

As it comes early in his abstract works if it's any form of grammar

it's an opening quote. When the show calls it “the starting point

for a wholly new approach to art”... well bugger me for a

know-nothing but they prove themselves right! Malevich was soon

calling this approach Suprematism, and crying

“arise comrades, and free yourself from the tyranny of objects!”

Realising

it in fact proved problematic, for such a large block of black paint

would inevitably crack over time. (Look up close at the illo above.)

To try and overcome this he repainted it four times, though it makes

you wonder why he didn't just stitch a square of black material onto

the canvas.

And,

there being multiple versions, we even get to see it twice. Just in

case you didn't get the point the first time. And in fact I'm not

being sarky there. In December 1915 he staged 'The Last

Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10', which doubled as the

first Suprematist show. (The only known photo of it is above.) This

is duplicated by the Tate, though more sparsely as only twelve of the

original twenty paintings have survived. And seeing it in this

context, rather than standalone, gives it more meaning. Hung across

the top corner, its simultaneously part of and outside and above the

other works. Notably its been placed next to some of the more

detailed pieces, providing a contrast. In fact, though I've no idea

whether this is actually the case, it looks like the other works were

made to go around it.

The

show makes much of this being the place where, in Russian Orthodoxy,

the icon would be hung in the home. (Ironically its also the place a

modern power object goes, the playback screen in shops showing

punters the security cameras are working.) There's debate about

whether this is meant as some Dadaist provocation or a genuinely

spiritualist gesture. My money's on the second one. In fact it made

me think of the way Hebrew scrolls would only use a placeholder for

the name of God, but still place that placeholder into a sentence.

The exhibition looks like it's built up as a sentence in that way,

the works as words, meaning stemming from context.

Yet

in a sense this all exhibits the limits of Malevich's approach.

Language always depends on context for meaning. It can point at the

ineffable, but only by contrasting with the here and now. Malevich

has expelled the representational from his art, but we still need the

represented - to see it framed by the real world for it to have

meaning. 'Black Square' needs the context of what

it isn't to be what it is. (I

had a similar feeling at the 'From Russia' exhibition, which included a photo of the

Black Square above the artist on his deathbed.)

Suprematism

Supreme

By

this point Malevich has successfully reduced his art down to one

colour, and one that strictly speaking isn't even a colour. Even the

off-whites which border his black shapes are so

off as to be no more than non-black, something to stop the eye

settling there. But, in the one moment of truth to the theory he

needed to pull back from the absolutism of 'Black

Square', colour then comes back in all it's boldness.

Take

'Suprematism 55' (1916, above) with it's bright

blocks of colour, even the background replacing the cold off-white of

'Black Square' with a warm sandy yellow. This

leads the show to claim “at the heart of Suprematism was colour”.

However, while colour is an important component, it's not the key

feature of these works.

The

Futurist dynamism he initially passed over for Cubism returns in all

its glory, and the colour is there to serve that dynamism. We can

think of abstraction and perspective as opposites, one seeing the

picture frame as a window on a world and the other insisting its just

a flat surface. But this work has a powerful sense of spatial depth,

that black tadpole floating as if several feet above the brown

rectangle. The diagonal black line emphasises the perspective, like a

dropping rope. Yet where Futurist dynamism was convulsive his is

elegant, those shapes seeming to serenely glide. (I know it's not the

point, but I can't help but see biplane shapes in there.) For all

it's abstraction it feels not sterile but alive,

full of movement. It provides everything 'Black Square'

withheld.

And

it's these works which carry the show. Notably it's this, and not the

better-known 'Black Square' which becomes the

show's poster image (up top). In fact, as Malevich started using a

black square in place of his signature, it becomes little more than

an authenticating rubber stamp, added to each corner.

With

Malevich it's easier to come at him from what he isn't doing, before

arriving at what he is. Miro called a series of painting

'Constellations', as if they were as vast and

awe-inducing as the night sky. While alternately, the first

atom-splitting experiments have been considered an influence on

Cubism. As we saw with Alexander Calder, he quite possibly combined

both. And indeed one of the appealing features of abstract art can be

having your sense of scale with-held, so you've no idea whether

you're gazing up at the immense or peering into the microscopic.

But

for Malevich either option – the cosmic or the subatomic – seems

still too earthly, too tied to regular human perception. It was more

like he was tapping into some heightened realm of pure geometry,

something which could only exist through being painted – but was no

less 'real' for all that. His term Suprematism does not relate to

'superb' but 'above' or 'beyond'. Works echo this in their immaterial

titles, such as 'Mystic Suprematism' (1920/22) or

'Supremacy of the Spirit' (c. 1920).

Robert

Burghardt and Gal Kim point out: ”The most obvious

strategy for representing universalism is abstraction. The abstract,

like the universal, evades the concrete. In the abstract formal

languages lies a certain openness that allows space for one's own

thinking and associations. It facilitates multiple interpretative

approaches and engenders fantasies.” ('Signal' 3, PM Press) (They're writing about Yugoslav Partisan

Memorials but the point transfers.)

”Everything

Has Disappeared”

And

this leads to a peculiar paradox with Malevich. The most active part

of his career coincided with the most politically eventful era in

modern Russian history. He went to Moscow shortly before the 1905

Revolution, fought in the First World War and witnessed the new

post-revolutionary Russia. It's events which led to the political

commitment of Rodchenko's photo-montage, Eisenstein's cinema or

Tatilin's vow to redesign everyday life. And yet among them here's

this mystic, his art self-avowedly removed from all earthly things.

To him surely those political events were like the off-white behind

the black square, not something worth focusing on.

Materialsm,

the idea that humans are products fo their social context, that we

cannot arbitrarily transcend that context just by thinking hard, is

axiomatic to communism. Suprematism seems the very opposite to all of

that. Surely it was merely an aesthetic movement with delusions.

And

yet he seems to have seen it differently. He claimed in 1915 “our

world of art as become new, non-objective, pure. Everything has

disappeared; a mass of material is left from which a new form will be

built.” And if a cynic might claim that as mere boiler-plate

Modernism, at other times he more explicitly tied artistic changes to

the political. In 1919 he stated “painting died, like the old

regime, because it was an organic part of it”.

Rachel

Spence writes of “the Russian avant-garde's fantasy of a social

re-ordering so radical it was often conceived in cosmic rather than

earthly terms”. ('Art Quarterly', Spring '15)

She is of course using the analogy to dismiss such hubris. But its

actually sound. If Malevich was other-worldly, there's also the sense

that events in this world had led us to more easily access that other

world. Revolution raised us, much like Mass is held to connect

Catholics to God.

He

taught art, and far from being remote or ascetic proved a galvanising

figure. His charges formed their own group, the Champions of New Art,

taking up the black square as their emblem. (Members included Popova

and Lissitzky, creator of the famous piece of abstract agit-prop 'Beating the Whites With the Red Wedge', 1919.)

The

Revolution, when it arrived, affected Malevich's art in two ways.

First there's the Architectons. Much like the Constructivists, he was

searching for a more practical application for art, so created works

which lay somewhere between sculpture and scale models for buildings.

But the truth is, they don't really work as either. As stated above,

Malevich's art needs a frame. It's subject was the ineffable, with

abstraction as a means to describe the indescribable. It works as a

kind of portal, an other-world only bordering ours. Objects which

physically exist in our space do not play to his strengths.

Also,

true to his words that “painting died” and “everything has

disappeared”, he again starts to strip elements away. The dynamism

disappears, and those pure blocks of solid colour dissolve. They're

as formal as the earlier 'Last Exhibition' works,

but instead of black-on-white they're... yes, really...

white-on-white. Check out for example 'White Suprematist

Cross' (1920/21, below). If we're going to continue with

our grammar comparisons, these are like the ellipses that trail off a

sentence like...

And

if that seems rather like a film that ends by fading to white, like

the story should really have stopped there, perhaps it should. But

instead...

Back

to Peasantry (Tragedy and Farce)

Stalin

soon rose to power, and it's scarcely a spoiler to say that part of

his plan to suppress all dissent was to impose a socialist realist

orthodoxy on art. Added to which, in a point played up in Orwell's

'Nineteen Eighty-Four', those who had earlier

shown an excess of zeal for the revolution were now considered

problem cases. What was wanted was those who'd just obey.

Malevich, in short, was primed to get it from both barrels. He had

only ever left Russia once, on a speaking tour of Germany, but that

was used as evidence of fraternisation with the enemy and proof of

“bourgeois” qualities. Many of his works survived only because

orders to destroy them were disobeyed.

Perhaps

unsurprisingly given the circumstances, he soon decided painting

wasn't quite dead after all and returned to the point most acceptable

to the new regime – the Donkey's Tail era. However, when his

peasants reappear, its history repeating as both tragedy and farce.

'Head

of a Peasant' (1928/9, above) is something of a sequel to

'The Scyther', but the eyes look heavy, the

mask-like face less universalised than stamped with the

dehumanisation of enforced collectivism. (In other works the main

figure has an alarming egg-shaped void for a head.) The figures

behind could be foraging as much as farming, while above them war

planes fly in formation before a darkening sky. As the show puts it

“his inert figures against a pared-down landscape convey a sense of

dislocation, alienation and despair. The peasant, long established as

the embodiment of the Russian soul, is reduced to a faceless

mannequin.”

You

could debate how deliberate all this is. Is Malevich like

Shostakovich, encoding the dissidence he couldn't state openly? Or is

he like Vertov, trying desperately to adjust to the new realities but

unable to sing the new slogans with any cheer? It probably doesn't

matter much. The result is the same. If some of his early works were

pastiches, these are almost pastiches of his own early work.

He

followed a career almost as neat as one of his geometric forms. But

unlike his patented square it was a triangle. There's a steady ascent

to the late Tens and early Twenties, at which point he seemed able to

lift himself from the ground, but which is followed only by decline.

Yet the view from that apex... it's no exaggeration to call it

other-worldly – so let's focus on that for the finish.

As

a general rule, I like to think of abstraction as something which

expanded the territory for art, freed it from being tied to

representation. Which is distinct from the notion of 'pure

abstraction'. If it instead switched art over, trading in hillsides

and rivers for squares and circles, then it surely swapped one set of

confines for another. It seems to make more sense to see those

normally regarded as the pioneers of abstraction, such as Kandinsky,

in terms of expansion rather than exchange.

So perhaps the most

fascinating thing about Malevich is that his abstraction was

pure, that he did disdain anything short of that as “a mere

imitation of reality”. And yet he found a way to make that work.

He's the man who made geometry glide and sing.

Coming

soon! More of this sort of thing...

No comments:

Post a Comment